Cameron's Book Reviews: Spring 2019

Alex is hard at work on the next episode — as Episode 8 is to Edgar, so Episode 9 is to me, so I’m very excited for it. Of course, we’re admittedly a bit behind: it’s inevitable. Alex works tech support, I’m an Adjunct, Charlie has a job at a museum. We’re not always able to put the time towards our creative endeavors that we would like.

One thing, however, that we can manage, is to read: we’re all avid readers, and we try to stay abreast of what’s going on with the written word. Here are some highlights from what I’ve read this Spring:

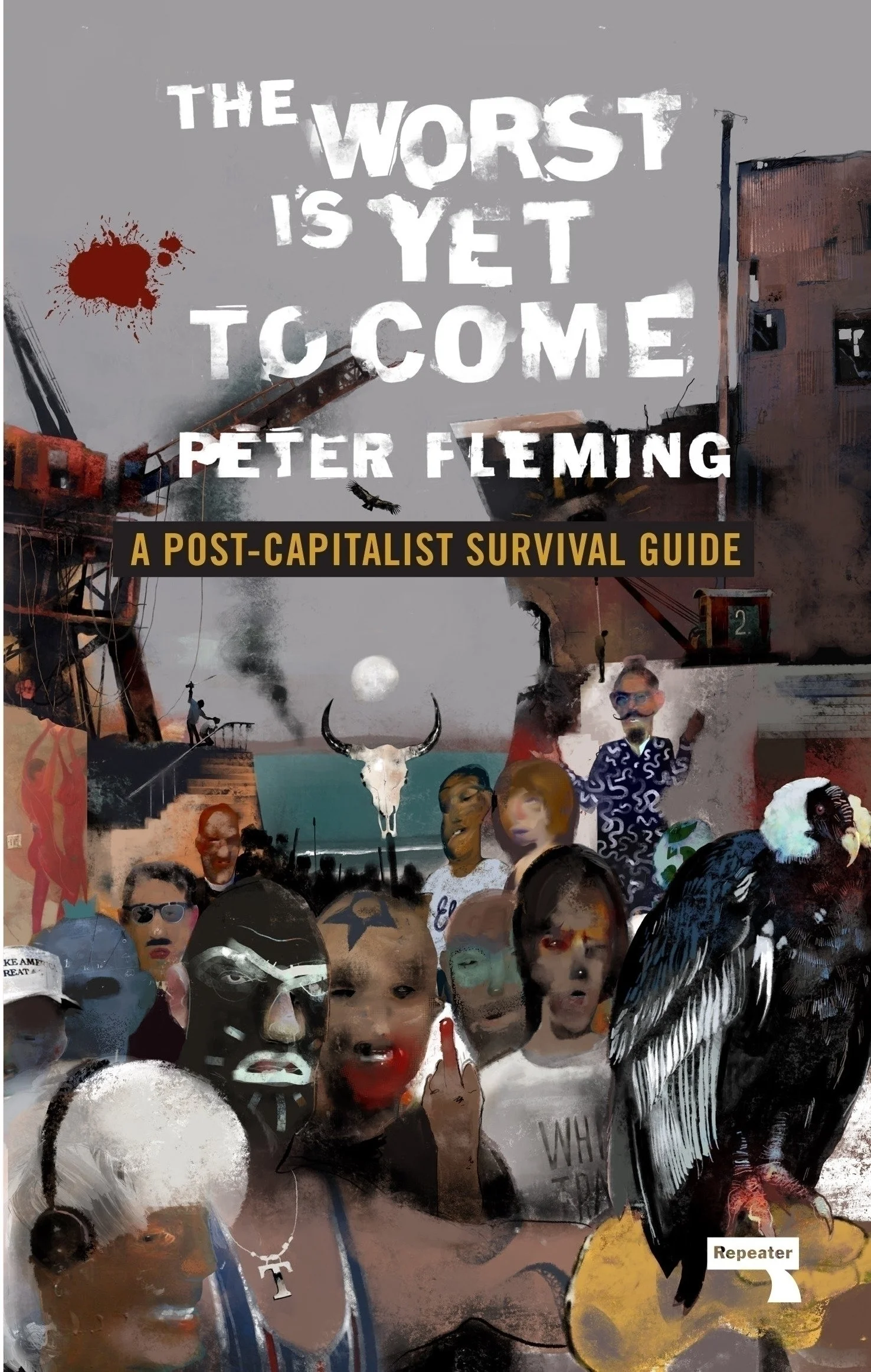

The Worst Is Yet To Come: A Post-Capitalist Survival Guide by Peter Fleming (Repeater Books, 2019)

Warren Ellis reviewed this one a little while back, and that’s what pointed me towards it, originally. The fact that it’s the one thing I’ve fond in the Venn Diagram where one circle is “Mark Fisher-related things” and the other is “Warren Ellis-related things” to be placed in the crosshatch sold me on it.

Fleming is a New Zealander who worked in London and meditated on the slow decline of Neoliberal Capitalism into something feral and malign — or, as he puts it at least once, “the same, but shittier.” It’s a work of “Speculative Negativity” where he despairs about whether any one of us can escape the situation we’re in, but holds out a sort of hope that someone does. It’s a survival guide (as the title suggests) and each chapter ends with a series of aphorisms and pieces of advice, ranging from “We’re asked to believe that writing useless emails all day is analogous to hunting and gathering in a previous age. We would perish without it. Biological self-preservation, however, is not secured through modern work…increasingly, the opposite is the case” to “Fuck Big Data.”

It’s a solid read, highly recommended, if only because it will make you think — it’s a bit on the short side, and I would have liked to see more meditation on what he’s bringing up, working it all together, but it’s entirely possible that this is too bloody an enterprise for someone to stick with for too long.

◆

Blackfish City by Sam J. Miller (Harper Collins, 2018)

The story of a city built on the ocean after the climate has turned. Qaanaak is a city without maps and without a history. People from all over the world, from lowly dispossessed refugees to New York Plutocrats fleeing the death of their city, have ended up there and constructed something new. Qaanaak is sustainable, vibrant, and riddled with the same greed and corruption as the old world. It’s a city where a mysterious disease, called “The Breaks” threatens the social order. People in Qaanaak don’t talk about their past, but the Breaks cause those who suffer it to experience the memories of others before they finally pass, before their body breaks and their mind slips out.

And the match thrown on this powder keg is the Orcamancer: on page 1 of the book, a mysterious woman arrives in a boat pulled by an Orca, accompanied by a polar bear with its jaws muzzled and its paws caged, and begins to set about her work — which, given her accompaniment and martial bearing, can’t be anything but bloody.

The book is quite good — it has a great plot, and stellar representation of both characters of color (I read the Orcamancer as Inuit, and there are characters from China and India, as well as a very prominent black New Yorker,) and queer characters (both homosexual and nonbinary characters are represented, and the story of the Breaks seems to be consciously modeled off of the AIDS epidemic, at least in how people respond to it. One downside, though, seemed to be that sometimes the characters took actions solely to forward the plot instead of because it’s what they wanted.

◆

The Water Knife by Paolo Bacigalupi (Alfred A. Knopf, 2015)

I really enjoyed Bacigalupi’s first novel, The Wind-Up Girl, and thought I’d catch up on his latest a while back. While The Wind-Up Girl seemed to be a biopunk reworking or send-up of Madam Butterfly, The Water Knife is pure post-global-warming James Bond.

In a future where the Western states of the US covertly fight one another for control of the finite supply of water, one of the major power players is the head of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, Catherine Case, and her weapon of choice is a man named Angel Velasquez, a so-called “Water Knife” who is tasked with the black ops side of securing a constant flow of water for Las Vegas. Oftentimes, this means trying to stay a step ahead of the operatives of California, the other side of this Cold Civil War that they find themselves in. Much of the plot concerns his attempt to figure out what happened in Phoenix, Arizona, where one of his confederates was killed in a most brutal fashion.

Or the plot concerns Lucy Monroe, a journalist documenting the decline of Phoenix, who has seen more than her share of “swimmers” — dead bodies dropped without ceremony in abandoned swimming pools. She begins a crusade, however, when one of her friends — a lawyer — is found tortured to death, after apparently finding the holy grail of this drought-stricken world, water rights supposedly “senior to God.”

Or the plot is about Maria Villarosa, a young Texan refugee who has been recently orphaned, and who is trying to escape to California or someplace north, anywhere other than Phoenix. And while things begin to look up, she is caught in a horrifying situation and must try to keep her head above (metaphorical) water.

It’s a good book. Very quick and readable, and Bacigalupi does a good job of emulating his chosen “text” without simply copying it into a new milieu. On the other hand, much like The Wind-Up Girl, it’s a frustratingly narrow look into a much wider world, and there’s a definite desire to see past the edges of the text. Just how localized is the drought, anyway? Does this link up to Wind-Up Girl or does it connect to the stories of Pump 6?

◆

Currently Reading

Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, volume 1 by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (Penguin Classics, 1972)

A most frustrating book. But there’s a lot going on there.

It’s a work of ethics, or political science, or psychology, or ontology. It synthesizes Freud and Marx, where it isn’t talking about Artaud and Nietzsche.

The principle subject is the Body without Organs and Desiring-Machines. Whatever those are.

The upshot is that it’s a very strange book, which I’m not quite prepared to give a complete review of. On a global level, it’s nonsense, and on the level of individual sentences, it’s full of profound aphorisms.

When it isn’t the reverse.

I don’t know. I really don’t know.