Escaping the Prison of Contingency: Another Attempt to Pin Down the Utopian Impulse

Image taken by Matheus Viana (Pexels.com)

As I work on this blog, my writing is developing – I've been writing things for years, but this is the longest sustained burst of nonfiction writing I've ever engaged in and I've received a few good very good pieces of feedback relating to it. The problem with any art is, as you get better at it, you get a better idea of what you want out of it and you feel like you're getting worse. This can get discouraging.

It also means that when you look back on what you've done, you feel that your prior work is insufficient. That it didn't live up to your current standards – as if your current standards are the standards you will carry with you forever, and you won't become dispirited looking back on your contemporary work (self-awareness can be a curse sometimes) – and you are gripped by a desire to go back and fix your prior work.

So, looking back, I'm dissatisfied with the writing I've done previously on the thing I'm calling the Utopian Impulse, which kicked off the current rush of aesthetic writing, and I want to try marry it to some of the ideas I talked about in “Reality Gives Way to the Real.”

I'm going to leave those pieces up, but I want this to work as a replacement for my explanation of what I mean when I say “Utopian Impulse” from here on out.

So, I'm going to start by discussing basic concepts.

Utopian Impulse as Theory

Father of psychoanalysis, social critic, and famed cocaine enthusiast Sigmund Freud.

Sigmund Freud proposed two basic drives within all people: The Pleasure Principle, which encourages us to do that which feels good, and the Death Drive, which is the tendency of something living to transform into something non-living. When you light up a cigarette, the Pleasure Principle and the Death Drive are acting in concert, you are performing an action that is pleasurable in the moment but which you know cannot help but hasten your own death. Generally speaking, Freud posited that these two drives governed human behavior.

Other theorists have other concepts, and Freud doesn't have a lot of currency in psychotherapeutic circles, for very good reasons. However, as a social commentator, he still has a bit of cachet.

Consider, George Trow in Within The Context of No Context discusses the caustic effect of television on our ability to form a coherent world-view. The grids of social interaction that Trow discusses melt away, turning society from a flawed but functional machine into a slurry pushed and pulled about by market forces and pop culture. What had once been a solid landscape turned into a sucking bog and no one is able to get any kind of traction because of it.

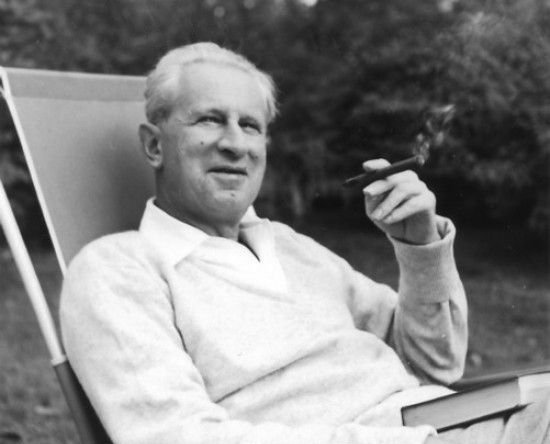

Herbert Marcuse, one of the fathers of Critical Theory. Photograph taken from wikipedia, copyright holder the Marcuse Family, represented by Harold Marcuse.

This echoes some of the ideas that come up in Herbert Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man, where American society is painted as implicitly totalitarian, choking away freedom not by putting boots to human faces (though, for many Americans, especially those of racial, sexual, or gender minority groups, as well as those suffering from mental illness, the removal of the boot would be a vast improvement,) but by throttling the number of options. If it doesn't occur to you as a possibility to walk away from your job, they can slash your pay and benefits and still see you show up the next day, no jackboots required.

Consider, also, Post-Modernism insisted that everything is culturally constructed, and many post-modern philosophers felt that to be a wretched condition: if there is no supreme truth, then that meant we had been wrong about everything, and there was no reason to value La Sagrada Familia over the Cheesecake Factory.

What I am calling the Utopian Impulse is a hypothetical third drive, something to break the Freudian dichotomy of sex and death. What Marcuse called “The Great Refusal” and Mark Fisher called “the Specter of the world that could be free”, I view as expressions of the Utopian Impulse. I don't want to think of it as anything mystical, but I can't help but feel inflected by mysticism when I discuss it. It is a haunting spirit, a radical outside, an alchemical potential.

Essentially, and here's the basic idea, if we accept that the systems of the world are contingent, that they have no underpinning except a critical mass of consent to them, there is no reason not to revise them when they prove insufficient or flawed. This momentum towards revision and experimentation is the Utopian Impulse. We have been trained to arrest it through so many means, we have been robbed of many of the necessary tools, but some of them remain.

Utopian Impulse as Praxis

Robert Putnam writes about this phenomenon in the book Bowling Alone.

An effective praxis for the 21st century has to be both individual and communal in nature. While a major problem is the atomization of society into a “social foam” where everyone is trapped within a personal empire of signs, we have to acknowledge the problems of beginning with collective action. My conviction is that, just as we cannot fix the world or ourselves through individual acts, we cannot start the work by forming committees. It seems to me that when we unshackle the Utopian Impulse, we have to do it in a way that provides both a quick personal benefit and an opportunity for interlinkage between people: develop a practice on this principle, inspire others to fashion their own practices that make use of that framework but mutate it, and then connect with them to become more than the sum of your parts.

The natural home for this is the arts. Artwork that rejects slavish realism and lavish spectacle, that is built on the engine of questioning the contingent, on undermining established form and experimenting and risking failure, begins to tap into the Utopian Impulse. When you do this, you're scratching a hole in a wall and allowing light to pour through.

However, despite the emphasis that this blog places on aesthetics, I don't want me saying this to turn into claptrap about how “stories are important” or “art can save your soul”. Those are tired themes that keep getting rehashed, and as Michael Moorcock once said “Jailers love escapism – it's escape they can't stand.”

It has to begin in the arts, but it cannot end in the arts. Our stories can be experiments we run to test the limits of what is thinkable, and projects to build bridge to new cognitive spaces. Our songs can inspire an outpouring of energy. Our paintings can show the way. But these are just the groundwork, they're the first, faltering steps when we have to start running as soon as we can.

The Fisher Wavelength: Acid Communism

The late Mark Fisher, who I’ve written about extensively.

Mark Fisher's great unfinished work was to be called Acid Communism, marrying the psychedelia of the 1960s to the Marxist project. Or, rather, showing how there already was a connection, how the consciousness revolution of the sixties and early seventies had real revolutionary potential.

He tragically killed himself before he finished it.

In all honesty, I was slightly disappointed to see what it is: Fisher had struck me as an innovative thinker, and I suffer from a bit of the “hippyphobia” that he was accused of before he began Acid Communism – a formulation not analogous to homophobia, but shying away from the ridiculousness of the psychedelic project due to the behavior of those involved (though I've tossed them aside since, I was always more a fan of the Beats than the Hippies. There was a hipster respectability to the Beats that was seductive when I was in college.) I had hoped that Acid Communism would be something new, a libidinal formation that broke from the psychedelic movement, pre-existing Marxisms, and seem like something new: I thought that Fisher's work would form a complete work stretched across a greater span of time. I wanted to see it as the problem articulated in Capitalist Realism and Ghosts of My Life, the tools to correct it found in The Weird and the Eerie, and Acid Communism as the completion – or at least continuation – of that project, the prescription, to follow after the diagnosis. Examining the introduction, I think that it may have been a step along that path, but not a culmination.

I was raised Catholic, perhaps I'm just vulnerable to messianism.

This is not to say that the formation that was to be described in Acid Communism wouldn't have been useful to examine. The whole project, I understand, was kicked off by the theorist and writer Jeremy Gilbert pointing out to Fisher during a talk that, unlike the punks which were held up as true rebels “Jerry Garcia had never advertised car insurance” (as related in the wonderful piece “My Friend Mark”, written as a sort of electronic obituary.)

I think that Acid Communism, Fisher would have settled on something like the Utopian Impulse, but much of his work was dedicated to articulating – clearly, simply, and beautifully – the nature of the problem. There are, at times, flashes of some kind of praxis drawn from his work, like the illumination of a lightning bolt over and unfamiliar landscape at night, but it is brief and intermittent, possibly the force of forward motion was arrested by his depression, but I don't know. In retrospect, I think that his writing in The Weird and the Eerie is the closest to a plan forward, where he begins to examine the nature of presence and absence, though it is too rarefied to turn into a praxis.

The Trow Wavelength: “Think of the Children”

George W.S. Trow, photo taken form the New Yorker. His work has been touched upon previously on this website.

George Trow, on the other hand, spends no time looking towards a solution. He was a polemicist through and through, and his landmark essay Within the Context of No Context only ever offers implicit solutions and ways of thinking toward solutions. It's tangled mass of interconnected ideas, and it's all too easy to pick one of his threads and follow it to completion without getting the point, because it intersects with dozens of other lines of argument, and each acts and reacts in concert. In short, it's a nonlinear Rube Goldberg machine of critical theory, which may sound like I'm looking down on it, but I assure you it's quite the opposite: Trow deserves more attention, and at another time I plan on giving him that attention.

One of the pervasive threads in Within the Context of No Context, to pick a tree out of the forest for closer examination, is the attitudes of contemporary American – I'd say Anglo-American, but I'm American and everything looks like weird America to me – towards children. There is a puerile obsession with childhood and the artifacts and accidents thereof: children and the accoutrements of childhood are an all-pervading guiding principle in western society. Everything is for the benefit and safety of children, but we so poorly understand the needs of childhood that we're unable to actually do anything properly in regard to it.

Perhaps one of the most clear of the aphorisms that Trow puts forward is that

“Adulthood” in the last generation has very little to do with “adulthood” as that word would have been understood by adults in any previous generation. Rather, “adulthood” has been defined as “a position of control in the world of childhood.”

This is follows up with the statement that “Ambitious Americans, sensing this, have preferred to remain adolescents, year after year.”

However, this dissolving of the adult context means that adults are essentially trapping themselves perpetually within the realm of preparing for adulthood – Roland Barthes makes the point in his essay “Toys” (starts page 8, listed as page 53) that much of childhood is simply conditioning people, preparing them for adulthood. So people are forever preparing to take a stage that they will never walk on. That is how we have ended up at a moment in history when so many people are playing at adulthood, where the highest executive in our government is playing at being a president, where one of the most popular forms of entertainment (video games) and the finance industry both revolve around what my friend Byron Gilman-Hernandez (former producer of the Eloquentia Perfecta Ex Machina podcast) labeled “the bureaucratic pleasure of watching numbers get bigger.” The ludic impulse in culture can be a good thing, but it has to be subordinated to something else. There needs to be some kind of responsibility.

Oddly, at the moment we find ourselves in, unshackling the Utopian Impulse might mean growing up instead of holding on to childlike wonder. If it doesn't, in actuality, mean growing up with the wonder intact: it could be that the process of growing up has become about paring away the childlike traits of a person, and leaving behind those that are simply childish.

Alchemy

The Squared Circle, a symbol of the Philosopher’s Stone, a central concept in Alchemy.

This may seem like an aside, but I promise it's connected.

My guiding mental framework for this project is Alchemy, the proto-science of chemistry that C.G. Jung held up as a prototype for his archetypal psychology. On the surface, Alchemy was about harnessing physical processes to transmute base metals (lead, iron) into perfected metals (gold.) Beneath the surface, it was about transmuting everything base (like the person doing the alchemy) into something perfected (an immortal being – or, alternatively, a completed person.)

In short, there were Alchemists who didn't misunderstand chemistry (though “misunderstand” implies that they had the tools to properly understand,) but were using it as a coded language to talk about striving towards completion and perfection as people.

This is an excellent metaphor for the process of creating art. You take the raw material of lived experience: the disappointment, the heartbreak, the confusing episodes where your life brushes against someone else's, the moments of joy and connection, and you turn that base matter into something else. You weave the odds and ends together to make a story or a song or a painting, and you hold it up to the world.

In my mind, the magnetic attraction, the force that welds these things together, is the Utopian Impulse.

I also think that an effective praxis for the 21st century is going to have to do the same thing: alchemize together all of the different lived experiences of people, and construct them into an artful approach to the world that gives us a path through the challenges facing us.

There are already some encouraging steps in this direction, but they are moving slowly, and I think that they need to accelerate.

In the Arts

Gary Gygax at Gen Con in 2007, photo taken by Alan De Smet, through Wikipedia.

Especially important to mention when discussing the Utopian Impulse – I feel – is the youngest analog art form, which is the tabletop role-playing game. This is a new art form, which takes the social contract as its medium just as poetry takes language or sculpture takes stone, and which could have emerged at any time, but which was invented at a particular time (1974) by a particular group of people (principally Gary Gygax, though other people were involved.)

One of the hosts of a favorite podcast of mine, J.F. Martell of Weird Studies, commented that he saw tabletop role-playing games as an evolution of the séance, with the Game Master serving a similar role to the medium, painting a particular world for the other participants to occupy. When I listened to this episode, I thought back on my long history of playing these games and a realization struck me: that the game was an evolution of the séance felt true, and what was being channeled was this utopian impulse. Consider: these games have experienced a major spike in popularity in recent years, partially driven by streaming and podcasting. I think a major part of the vast increase in popularity that Dungeons and Dragons, the flagship game of this genre, has seen outside of the traditional “nerd” community is the fact that a number of LGBTQ enthusiasts have determined that they can use this to tell stories that take place in a world presented for them – a world where, for example, homophobia just doesn't exist and their stories can be about them without having to be about how other people hate them just for being who they are.

But one of the main benefits in this art form is that it is fundamentally an art form that takes the form of a toolkit you're supposed to use to construct your own stories – if you're not testing it to its limit, you're not fully making use of it. Moreover, because of the shared nature of the narrative that emerges no one – not even the game master – knows how the ending is really going to go. Doing it properly involves removing the creative shackles and allowing the impulse to flow in, while also engaging in a communal activity.

In short, it makes every active consumer of the medium into an artist, democratizing it without cheapening it. If you’re interested in knowing how such games work, I highly recommend the Gauntlet podcast network’s output — especially Pocket Sized Play (the episodes tend to be fairly brief. Other Actual Play podcasts can reach multiple hours per episode.)

I would also say that, when done right, speculative fiction also displays the Utopian Impulse – not in the open-to-all form of tabletop role-playing games, but pinned and dissected so that it can be understood. This is only true when it actually seeks to push the envelope: the works of Ursula K. LeGuin come to mind, as do those of the writers of the so-called “New Weird”. Early Cyberpunk suggested it, but as time went on the genre degraded from a trailblazing experiment to a mere syntax of expression.

Another good venue for finding it in literature is in OuLiPo (mentioned in Edgar’s last book round-up), as these works do a great deal to explore the contingency of the “rules” that much of literature operates under. By imposing new ones, the old ones can be examines as purely contingent exercises. This logic was extended later by the Situationist Internationale, who examined the contingency of the meaning systems that surround works of art and examine the capture of art by mere spectacle, which alienates people from their day-to-day life.

In Religion

Tibetan Thanka of Bardo. Vision of Serene Deities, 19th Century, Giumet Museum, taken from Wikipedia article on the Bardo Thodol.

Another wellspring, and this may seem paradoxical coming from someone who isn't even really an agnostic, might very well be religion. Religion has been perverted to a number of awful ends: atrocity piled upon atrocity, in the name of the divine. But it has also been a home for the arts, and a powerful source of motivation outside of the framework of capitalism.

The counterculture of the 1960s drew heavily from Tibetan Vajrayana mysticism, as Fisher notes in the introduction to Acid Communism, but perhaps history might have gone differently if they had been looking towards the Judaic concept of Tikkun – the rectification of the world – instead of the Buddhist Nirvana – escape from the world.

Of course, either way is appropriative, but religion is one of the channels of expression that exists partially outside of the frameworks of capitalism that can serve as a jumping-off point. There are certainly dark forces at work within religion, including the Christian Prosperity Gospel movement, Islamic Wahhabism, or Neopagan Folkish movements and other expressions of similar – but acknowledging the existence of these tendencies within religion doesn't mean that religion need be thrown out. After all, there are fundamentalist atheists in the world who can display a similar fervor.

I'm not going to plug a particular religion here – as mentioned, I'm not really anything – but any system of thinking that allows you a vector of escape from the predominant mindset, without requiring you to do anything monstrous to follow it, is good.

All of this being said, I feel that there is something useful in esoteric thinking: not to the exclusion of science or philosophy, and not simply for the sake of hidden knowledge, but there is a trend in scholarship which seems to suggest that things like alchemy, gnosticism, and hermeticism may have an analogic or metaphoric connection to practices related to contemporary psychology, and they are rich storehouses of metaphors in their own right.

In Movement

Downtown Mayberry, still the archetypal American small town, decades on.

It's a common bromide that travel expands your horizons, and this is true. One of the most important things I ever did for my development as a person was spend six weeks in France – something that I was very lucky to experience, due to a confluence of working an online job, and having people willing to provide me with food, board, transportation, company, and additional work. I have difficulty putting up with a temporary inconvenience: I can't imagine being patient enough to put up with a whole additional person for six weeks.

I didn't stay in Paris, I stayed in a small town in rural western France, an hour or so outside of Nantes. It was a very different way of life and it's one that I'm not sure I could permanently adopt, but that's exactly the point: I wasn't even aware of the mechanics of it previously, and now I have enough of an idea to know that the adjustment would be difficult.

Bridge Street in Las Vegas, NM, the smallest town I ever lived in. (Photo from Las Vegas Citizens Committee for Historic Preservation)

This doesn't just mean going to a different country. If you're a resident of the United States, travel in the area you're in. If you live in the country, go and spend a day in the city – if you're a resident of the city, go and spend a day in a small town. Eat someplace you never considered. If you feel safe, have a conversation with a stranger.

The world wants – as much as it wants anything – for you to feel alone and afraid of the people around you. While there are dangers out there, they are outweighed by the dangers of going it alone.

Praxis

So much of critical theory is just that: simply theoretic, without a practice to put it into action. Oftentimes it's simply a commentary on the sorry state of the world and how impossible the dream of a better one is to achieve. After all, as Acid Communism was going to describe, the last time we dreamed of a better world it landed us in the 1980s; and as Within the Context of No Context suggests, we're so atomized that we've reached the point where we can't even see the middle distance of our social world: there is only ever the nuclear family or the teeming mass of humanity.

The Utopian Impulse demands a praxis. After recognizing the contingency of everything in our culture and society, we must examine the world as it stands and dream a better world. Then, we need to try to purposefully move in that direction. If the world makes us feel sad, angry, and alone, we should identify the reason and pull it up by its roots.

I say this because our current moment – one of a rising tide of authoritarianism, of climatic emergency, of epistemic uncertainty – needs us to. We don't have the option of staying where we are, or wallowing in abject failure, so we need to rebuild the world from bottom to top.

And if we are going to have to rebuild the world, we must do our best to make it equitable, beautiful, and meaningful.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference.