"I Am Back To Save the Universe": A Possible Reading of OK Computer

Mr. Nobody, from my beloved Doom Patrol, and also me in the garage booth.

As part of my job, I am sometimes called upon to be the guy in the garage booth who takes your money and lets you out. This means sitting in a glass-and-metal box in a subterranean parking garage for hours on end. It’s an existential nightmare. I mean, think about it: that’s some Mr. Nobody-origin-story shit. You’re alone with your thoughts, trying to get people to give you money as quickly as possible so you never have to talk to them again, and god help you if you get your scripts mixed up.

Because of this, we’re allowed to listen to safe-for-work music (or podcasts). Gotta keep it together somehow.

Yes, naughty children, it’s Radiohead time.

So one day, towards the end of the summer, when I was put on garage-booth detail, on a whim, I put on Radiohead’s classic album, OK Computer. It’s been in heavy rotation ever since.

During the course of that day, my coworker — a fresh-faced kid whose art is fantastic — popped in a few times to let me know how things were looking. The news was always bad; we’d been having technical difficulties on a number of the things that get people’s money away from them and get them away from me, and there was a confluence of events that meant that the garage was busy.

On one of these visits, the poor thing got treated to me explaining why Radiohead is good. She’s not a music nerd, which meant I got to spout classic platitudes about Radiohead without her recognizing them as such. I feel bad about it now, and felt worse about it partway through said rant when I realized that I had not listened to that much Radiohead, actually.

The kicker? She’s the same age as OK Computer.

※

Also that album cover is very much what suddenly-living-in-a-dystopian-hellscape looks like to 13-year-old me.

I first discovered Radiohead through hearsay. I was in my early-mid-teens, and my dad was buying Uncut and other music magazines, mostly for the free CDs. I’ve mentioned the impact his gift of these magazines had on me before, I think, but that’s how I heard about Radiohead: through adulation in the primarily-British music press, though I also recall seeing a Paste write-up of Hail To the Thief at some point. In any case, I was still using dial-up at the family farm in Pennsylvania, and also I didn’t know many other children, so I didn’t actually know how to use things like Napster or whatever people were using around 2003. I had only heard of this band, and then in the vague terms of established greatness. I was clearly missing out on something, so went to my source for music in my allowance-less youth: my dad’s CD collection.

There may or may not materialize a separate post about that collection, and what I found there, but for our purposes today, I found only Kid A, Radiohead’s 2000 album, which featured a then-groundbreaking promotional model and a lot of synthesizers.

I was smitten.

※

So call it more than fifteen years I’ve been sort of casually a fan of Radiohead. I’ve listened to a little bit here and there, but for a long time, my sole experience was Kid A. It served me well: the album heavily deals, or seemed to me to deal, with issues of social alienation and the digital world, and I was a queer kid in a conservative milieu who went to an online high school after being home schooled my whole life prior.

Beyond my personal background, I found a broader, social solace in the album: the gorgeous, enveloping sounds the band developed over the famously-difficult recording process helped me, in a way, to make sense of a world in the wake of September 11, one that had not changed as I had thought it would, but had instead become an eerie and degrading copy of the world I had been promised. You don’t have Thom Yorke crooning “I’m not here / this isn’t happening” in your earholes while looking out at the world as it appeared in 2003 and not feel like that sentiment might actually represent a reasonable response.

So why didn’t I follow up with it? Why didn’t I get excited about Radiohead?

Quite frankly, I felt like I didn’t need to. The hype was accurate, and also very real.

Honestly, they didn’t look like they needed fans so much as a hug, which seems to have been accurate.

※

Also in 2003, I encountered a piece of critical writing that has forever fucked how I read things. In the inaugural issue of The Believer, which my dad got on a whim from fucking Borders, it was that long ago, there appeared a piece by Jonathan Lethem on how and why to read Charles Dickens, entitled, “Dickens: Greatest Animal Novelist of All Time?”

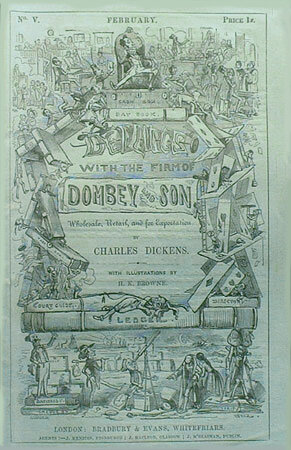

Lethem’s essay focuses largely on Dombey and Son, of which this is a serial cover.

In the essay, Lethem makes the suggestion that one of the better ways to argue for why one ought to read Dickens is because, barring reading his works as something else, the reader is faced with the nigh-impossible task of reading his works as they are, which Lethem and, as his citations show, many others believe to be pretty much everything, at least as far as English letters go. While that’s neither here nor there, the concept — that you can read things as whatever genre you want them to be, as long as it works, as long as it lands for you — became a cornerstone of how I read books. It comes out most frequently when I read philosophy, but it frequently applies, especially to older fiction. (More contemporary works, written as they are in the flickering light of film, read functionally as movies, which makes things fairly straightforward.)

Radiohead may or may not in fact need you to like them; Thom Yorke spoke recently about accepting his fate as a public figure with fans and stuff (NB: link to NYT), and seems at least cool with people liking them/him, and obviously, this is his job, so people listening to their music is in his best interests. By contrast, Dickens isn’t really in a position to give a shit that people read his books at all, let alone how they read them.

So where are we going with this?

One of several delightfully trippy posters for the series.

※

More recently, Cameron and I were watching an episode of Legion, the FX Productions series based on, basically, the Marvel version of Grant Morrison’s Crazy Jane. Towards the beginning of one episode, the arrival of several of the supporting characters at a facility that David Haller has ravaged in an attempt to rescue his sister is soundtracked by what begins as a gentle piano ballad, swelling to include string arrangements beneath the biting indictment of the lyrics.

“Who is this?” I asked Cameron, early in the song, because I love a sad man with a piano and a string accompaniment. “Is this Thom Yorke?”

“I think it’s Thom Yorke.”

“Let me look it up.”

It’s fucking Radiohead, because of course it is. Specifically, it’s “The Daily Mail.”

※

In the first episode of Community, the character of Britta is introduced. As part of her backstory, it is mentioned that she dropped out of high school because she thought it would impress Radiohead.

In my early teens, I encountered a young adult novel, the name of which I cannot now find. It was the kind of pretentious story about depressed high schoolers that was the best you could get before YA fantasy turned into something worth reading again, and as such, it featured a dramatis personae. And of course, the cool English teacher is characterized, in part, by the statement: “Listens to Radiohead.”

Everyone got mad when Malia Obama didn’t go see Radiohead at Lollapalooza that one time — remember that?

I don’t know, man, here’s a list of someone’s opinions on the best uses of Radiohead’s music in film, and here’s a Reddit thread with pop cultural references to Radiohead. Basically, what I’m trying to say is that this band has been a by-word for cool-but-sad for a long, long time now. And if we’ve all already agreed that they’re cool and the people who like them are cool, why do you need to listen to them?

※

I mean, come on.

As with a lot of things people agree are good but can’t seem to agree on why, I’ve struggled to engage with Radiohead’s decently voluminous discography in anything like a systematic way. After coasting on Kid A for years, I didn’t really engage with Zorp again until the release of Moon-Shaped Pool, the lead single, and attendant video, for which tapped into a fairly drawn-out love affair with Moral Orel and also is a fucking earworm. And that held me for a while, and I dabbled — Christ, Thom Yorke would hate this — because I could access all their music on Spotify, but nothing really stuck.

Until I got in the box and threw on OK Computer.

And now here we are, a few months later, after I’ve wrung out all the jokes about leaning hard into the 30-year-old alt-dude I-only-wear-black-and-I-listen-to-a-ton-of-Radiohead role, after at least one week straight during which I don’t think I listened to anything else.

So what do we do now?

※

Speaking of cool-but-sad and shorthand ways to communicate that, let’s talk about weird superheroes. They’ve come up a couple of times in the course of this piece, and I feel the analogy has legs.

Here’s the cover of the first issue of Morrison’s run of the thing and if that doesn’t sum it all up pretty well, I’m not sure what will.

As is probably very clear at this point, I fucking love Doom Patrol. I am not exaggerating in any way when I say that the trade paperbacks I collected of Grant Morrison’s run of the series saved my fucking life. This was, of course, a little after my introduction to Kid A; I had gotten much more depressed and even lonelier than I had thought possible in the interim, and I needed what Doom Patrol gave me.

And what Doom Patrol gave me, as you might expect, was odd shit — really, really odd shit — but also a model for emotional growth and acceptance in the face of deeply weird circumstances. For a variety of reasons (and how accurate I was in this assessment is debatable), I felt that my circumstances were deeply weird, and that my abilities and proclivities were deeply weird, and that because of that I would be forever doomed to a life of dull loneliness, punctuated by periods of baroque emotionality (and that was sort of accurate for a while). Robot Man, Crazy Jane, Rebus and the rest of them provided the best cultural model I had seen for how to respond to circumstances of what I was told were extreme talents, preserved in an isolated vacuum.

I liked X-Men too, don’t get me wrong, and I won’t now derail into an assessment of how Doom Patrol and X-Men differ from one another in focus. Suffice to say: X-Men brood, but the Doom Patrol acts out, in spite of everything — their powers that wreck their lives, their own traumatized responses to those powers and those wrecked lives, the secret machinations against them from a variety of sources.

They’re weird superheroes. And in much the same vein as the weird procedural, the weird superhero deals with The Weird in a very particular way — and frankly, it’s 50/50 whether “dealing with it” might not actually entail making friends with it, or at least empathizing with it and then gently mercy-killing it, depending on who’s writing the thing. That’s part of their defining characteristic, for me: the focus on character and emotionality in the face of Very Fucking Weird Shit.

※

I don’t need to tell anyone to listen to OK Computer. Everyone who’s going to has and everyone who means to has heard that they should from more authoritative and better paid sources than yours truly. But I generally feel the need to justify why I like things, beyond just a bunch of people saying that it’s great.

So just for fun I’m going to suggest that we take a Lethemite (Lethemian? Adjectivalization is silly) approach to things, and I’m going to suggest that OK Computer is an album about weird superheroes. And this argument has probably been made before, but I’m pretty pleased with it. After all, we hit all the beats of the weird superhero, and as they earlier-cite Paste review had it:

[Thom Yorke’s] protagonist remains the frail, hopeless survivor, facing off against an insurmountable enemy, offering covert warnings and coded stabs against apathy while awaiting his imminent destruction. His antagonist remains the faceless agent of power that reassures the innocent of their safety all while threatening swift annihilation.

I mean, that sounds like weird superheroes to me. So here’s a spin: after a horrifying accident (“Airbag); acknowledgement of powers (“Paranoid Android,” “Subterranean Homesick Alien”); collapse of the hero’s regular life (“Exit Music (For a Film),” “Let Down”); attempts to confront The Weird in conventional ways that do not work (“Karma Police”); an abortive attempt at returning to normality (“Fitter Happier,” and maybe also “Electioneering”), followed by a cathartic and destructive release of powers (“Climbing Up the Walls”). The hero recovers from this catharsis, possibly with another attempt to reject their powers (“No Surprises”), but then must face their nemesis in some way (“Lucky”) before acclimating to the new state of affairs, or like dying or something (“The Tourist”). It all tracks pretty well, which I guess is not surprising.

※

Again, I don’t think anyone needs to hear from me that OK Computer is worth their time. But if there’s one thing I love, it’s alternative readings and scrapping things for parts. So let’s give it a shot; let’s listen to this one, not as one of, if not the, great albums of the late twentieth century, but as a raw, emotional portrait of someone blessed with suck. It’s 2020 and we’re all going to die, so why the hell not?

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference.