Treating the Nostalgiac: An Overview

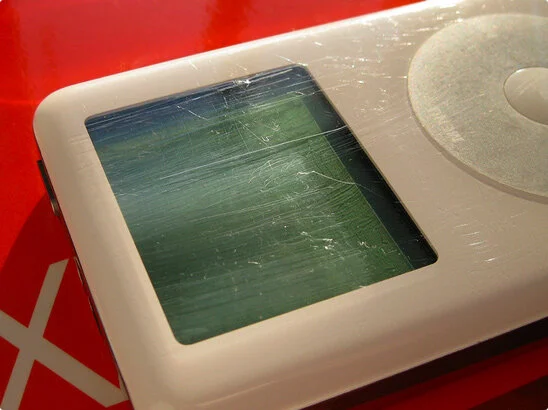

Both Used Future and Jobsian Minimalism, in one. (image taken from here.)

So, this is something of a continuation of last Wednesday’s piece “Desire in the Age of the Algorithm” – while that piece is a sprawling, political rant, I wanted to connect it to some aspects of things I’ve argued in the past, including “The Collapse of Possibility” where I talk about how science fiction is narrowing down into two general aesthetics (Jobsian Minimalism and Used Future.)

It’s been commented in the past that people in a lot of prestigious fiction – call it MFA fiction – live in an oddly nostalgic world. They don’t have cell phones, and if they visit the internet, it’s usually on a laptop. Everything is perpetually 2004 in an MFA story. I want to argue that something similar is happening to a lot of science fiction. A lot of science fiction is simultaneously more realistic to our current world than prestigious MFA fiction and written from the perspective of someone living within one of those stories. Like someone in a creative writing program is writing a story about a science fiction writer who understands what 2020 is like, but is calling the year in question 2030 or 2050 or the Year of the Depends Adult Undergarment.

But what of the actual future? The dark territory into which we are being inexorably drawn?

Oh, you mean the distant future, the year eight-thousand where we have figured out how to travel between the stars and everyone lives in lotophagic stupor other than our heroes, those future nostalgiacs that wear reproduction Nikes and love Will Smith movies? (you know, the same way all of our contemporary heroes are two-fisted scholars of Homeric Greek.) Where we have conquered the challenges of the Anthropocene and live lives of ease and plenty, except that it’s all still capitalism. That, right?

Sorry, I should have said “Converse”, not “Nike”.

Or maybe you mean the apocalyptic near future, where a thousand thousand rugged individualists wearing one-sleeved leather jackets wave around shotguns under a desert sun and fight over gasoline?

Or maybe you want a cyberpunk flavor, where the future is rainy and neon-lit and people use words like “chrome” and “chummer” like those aren’t the dumbest bits of slang ever conceived.

I don’t mean any of those.

What we have here is the return to older forms – the future imagined by the 40s-60s, the 70s, and 80s, respectively, slightly recast to show that it was written in the modern day. Ever since the 1980s, we’ve had a narrow cone of possible futures that occur to us, viewing the future by flashlight.

In short, just as I’m saying that Capitalism is pretending that the rate of invention has been fantastically accelerating, I’m saying that our ability to imagine new futures is being constrained – we’re claiming that old ideas are new ideas and acting like repackaging is the same as invention.

John Brunner’s The Sheep Look Up.

Not to get all hauntological, but it makes me long for the high weirdness of the New Wave – Phillip K. Dick, John Brunner (a man who described some things within spitting distance of reality in Stand on Zanzibar and The Sheep Look Up,) J.G. Ballard, Harlan Ellison, Norman Spinrad, and Roger Zelazny.

Of course, part of the problem is that the High Weirdness of the New Wave was caught in amber and then repeated over and over again, degrading each time.

I’m turning into a broken record. This is something I’ve said before a number of times, and it’s probably no fun to listen to – or read, as it stands – so let’s take a look at potential approaches.

Let us look at nostalgia itself, because nostalgia is what we’re taking aim at here. The pain of homecoming. Let us take a more medical or therapeutic approach. If we view being a Nostalgiac (a painfully essentialist phrasing, I know) as a bad thing, what is the treatment for it? What is the plan of action for rehabilitation?

Let’s refer back to some of the pieces I’ve previously written that touch on this. In “You Can’t Automate Enlightenment”, a piece that touches on a twitter beef between Grimes, Devon Welsh, and Zola Jesus, I wrote:

“This [the differentiation between knowledge and information] is important, because information can be quantified and commodified, but knowledge cannot be. If the two are the same, then a potent metaphor has been created, and knowledge can be bought and sold. Artistry can be bought and sold. And if it can be bought and sold, then it can be automated.”

When you take this into the discussion of nostalgia, I think you come upon the difference between that phenomenon and what we’ve called Metachrony. Nostalgia takes past forms of art and experience and treats them as information that can be repeated, mechanically and endlessly. We can build neural networks that predict how Johns Hughes, Updike, and Lennon approached their arts and just feed in current events to reboot 16 Candles or The Witches of Eastwick or The White Album for the algorithmic age, but it won’t ever speak satisfactorily to that age other than being an artifact of it.

Let’s move on to another one. In “Time is Out of Joint: Notes on Metachrony” Edgar concluded by instructing:

“Look back, because the way forward is blocked and we’ll need materials from somewhere. Gather what you can: break it off, if you have to; repurpose it to your own ends. Look at how people have lived, how we keep peopling all over the damn place and at every known time. We can’t rely on the principles and concepts that have hitherto molded our ways of understanding ourselves. As we search for comprehensible ways to think about things, we have to use the tools that we have to build a future we can live with; take them, whenever you find them.”

This is encouraging the application of knowledge of the past, instead of just the information we have previously used. Look deeper than the surface level features, what I have elsewhere called the “syntax” of events and look into what I’ve called the “paradigm”. The syntax can be automatically generated – individual component by individual component, probabilistically determined like the letters in a neural network’s composition (there is a 70% likelihood that an S will go here and a 45% likelihood that an E will go here; there is a 95% likelihood of a space after the S and a 21% likelihood of an H after the S…)

So what is that, what is “paradigm” and what is “syntax”? I break it down at the end of “Which Grain Will Grow, and Which Will Not: On Syntax, Paradigm, and Myth” by writing that:

“To summarize, every piece of narrative art (and potentially every piece of art – I’m inclined to think that it’s every one of them) has two “sides” to it. There’s the public-facing “syntax” that is what the audience experiences, and there’s the artist-facing “paradigm” that defines what syntaxes are possible. The syntax is the visual vocabulary, the dialogue, some parts of the characters, the setting, and the pieces that the audience can get at quickly; the paradigm is the tone, the theme, the events, and the parts of the character that aren’t part of the syntax. In our culture – in all cultures – there are ready-made myths that can be picked up and used as a paradigm by a creator . . . the identity of a narrative lies in what differences can enrich the story, instead of muddy the waters. Being aware of these two ‘sides’ can enhance your writing, can open up new possibilities.”

So here I introduce a third thing (actually in this piece, I introduce a third and a fourth thing – but I’m going to pass by myth right now and try to move beyond the narrative arts.) Difference is the key thing I bring up here.

Okay, you may say, I’ve taken a really long time and wasted a lot of electricity to get to the point of “make it different”, which is what this all boils down to, but it isn’t just difference for the sake of difference.

I will explain this with Samurai films, because that’s what occurred to me. There are two levels that you can employ difference on: the level of Syntax (Syntactic Difference) which is like the difference between The Hidden Fortress and Star Wars – similar events played out using a different visual vocabulary – and the level of Paradigm (Paradigmatic Difference) which is like the difference between Seven Samurai and Thirteen Assassins, both involving a group of fighters engaged in the defense of a village, but the former is aimed at the defense of the village and the latter is aimed at the death of the attacker.

Sukiyaki Western Django (2007).

Lastly, you can engage in difference on both axes, and still have a kind of genetic relationship in play. In a previous piece (“Unpacking the Trash Can of Genre”) I mention the relationship chain between Red Harvest/“Blood Simple”, Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars, and Blood Simple – there is a final, postmodern spot on that chain (directed by Thirteen Assassins’ director, Takashi Miike,) called Sukiyaki Western Django – a bizarre film that riffs on the connection between the second and third entries in this chain. It eventually, self-consciously, breaks down and diverges from the source material.

This film, though, I would say, is another example of the metachrony that we talk about so often here – it merges the aesthetics of the western and those of the jidai geki film (of course, given that both can be set in the 1800s, perhaps it’s better to call it cross-cultural than metachronic, but I’m the one writing this, and I think it’s an example of a metachronic aesthetic.)

If we take the metachronic to be about a sort of non-causal linkage between things separated by an indefinite gulf of time and space, that leads us to the work of Andy Goldsworthy, discussed in Edgar’s piece on the Walking Wall at Kansas City’s own Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. This piece juxtaposes ancient and modern in an interesting way, but the gap between the two opens up a new space:

“Goldsworthy characterizes projects-in-progress like this frequently as, simply, ‘the work’ — not by its name or title, but by what it is and how it’s made. The starkness of the word, its weight of connotation, its etymology even, speak to the nature of “Walking Wall” and Goldsworthy’s other large projects: deceptively simple to define and to construct but deeply situated in a temporal and creative lineage that gets weird and deep and old very quickly. It is work in every sense of the word, and in a society where ‘work’ is positioned as a calling and gains prestige the less stuff you have to actually do, being faced with several equally true senses of the word all at once is kind of a lot, and there’s manipulation or room to doubt that is there.”

Here, the artist-and-workman jargon calls up the history of labor – not Labor in the marxist sense, but labor in the day-to-day toil – and asks us to meditate upon it, asks us to think about the timeless-seeming interplay of permanence and solidity on one hand and transience on the other.

Let’s take this from another angle, referencing one of the more unique narrative and aesthetic experiences that we’ve detailed on this website. I’m going to call up “To Breathe the Sacred and Terrible Air: On Disco Elysium by ZA/UM” – one of the most widely read pieces we’ve put up, and which also meditates on the metachronic nature of the subject matter.

Planescape: Torment (Black Isle, 1999)

As an aside, though, Disco Elysium is generally an example of something that appears nostalgic but isn’t. It’s often compared to Planescape: Torment, a game from 1999, which had its own followup in the form of 2017’s Torment: Tides of Numenera (a roleplaying game that relates to the Numenera RPG mentioned in the piece from Edgar that I quoted earlier.) I would argue that Disco isn’t a nostalgic throwback, but a worthy followup, insofar as it took what worked in Torment (a story that centered not on some vast, world-shaking event, but principally on the experiences of one character, but drawn on the same epic scale. In short, what YIIK should have been, but decidedly was not.)

In that piece, I wrote:

“The world of the game is vast and complex, but you never leave a single neighborhood, Martinaise, a lower-class industrial neighborhood in Revachol, formerly the capital of the world, but now under occupation by the other nations of the world. The nature of this ultra-tight focus is commented upon in the VICE review of the game, which was part of what encouraged me to take the plunge and actually buy it. The emphasis on location and hyperlocalism really drew me in, but it wasn’t the only thing that helped me enjoy the game.”

And I think that this is one of the biggest insights that I’ve ever come across, and one I still struggle to internalize and work with: sophistication, artistic virtuosity, sheer brilliance isn’t a matter of scale. Something can be tiny and revolutionary; something can be vast and old-hat. It isn’t just about numerical increase, it’s about newness.

This is why Ulysses, by James Joyce, is the landmark that it is: yes, it’s a large work, but the brilliance isn’t in the size, it’s in the fact that, with this book as a guide, a future civilization could reconstruct early-20th-century Dublin cobblestone by cobblestone. It’s not notable for being long, it’s notable for the amazing granularity of the text. It sinks into the hyperlocal qualities of Dublin and unfolds them for the reader.

This is fundamentally, the same point as I made about capitalist technological development in “Desire in the Age of the Algorithm”: simple numerical increase – as my friend Byron once described it, “the bureaucratic pleasure of numbers getting larger” – isn’t innovation. Simple increases in scale aren’t innovation. More isn’t innovation, but neither is less.

Innovation comes from zeroing in the the places where difference can be interesting or engaging, by encouraging benign and beautiful mutation in the substance you are working with. To your audience it may be unusual, it may be downright uncanny: but it may allow you an exit from the walled garden of nostalgia, into new and uncharted territory.

And so, we have here some options for the treatment of the Nostalgiac:

First, the rejection of simple information-based nostalgia in favor of the application of past forms of knowledge, producing Metachrony.

Second, emphasizing Difference and genetic drift to separate out future options, not settling for mere evolution but for mutant variation.

Third, eschewing scale, and numerical increase, in favor of fine-grained representation and fine-tuned alteration.

I don’t think these three things are mutually exclusive. I will say that I think that the first point can be moved beyond – bringing in the modes I described in “Flavors of the Strange” under the names “Wondrous” and “Apostatic”, described as

“We can call the hypothetical twin of the Weird ‘the Wondrous’ – the edges of the symbolic order cracking and letting in a healing light.”

And the other I describe by saying

“What if we invert this: instead of the intrusion of the outside into the inside, what if this is the escape from the inside of the symbolic order: the Escape to the Outside . . . Maybe the twin of the Eerie – let’s call it ‘the Apostatic’ – isn’t all that gentle, isn’t all that nice, but offers something we need. A bitter medicine that we can choke down and rely on to make our escape.”

I don’t view these three approaches as mutually exclusive, and I think that bringing them all into our toolbox might allow us to unmake the trap of nostalgia that we find ourselves in.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference.