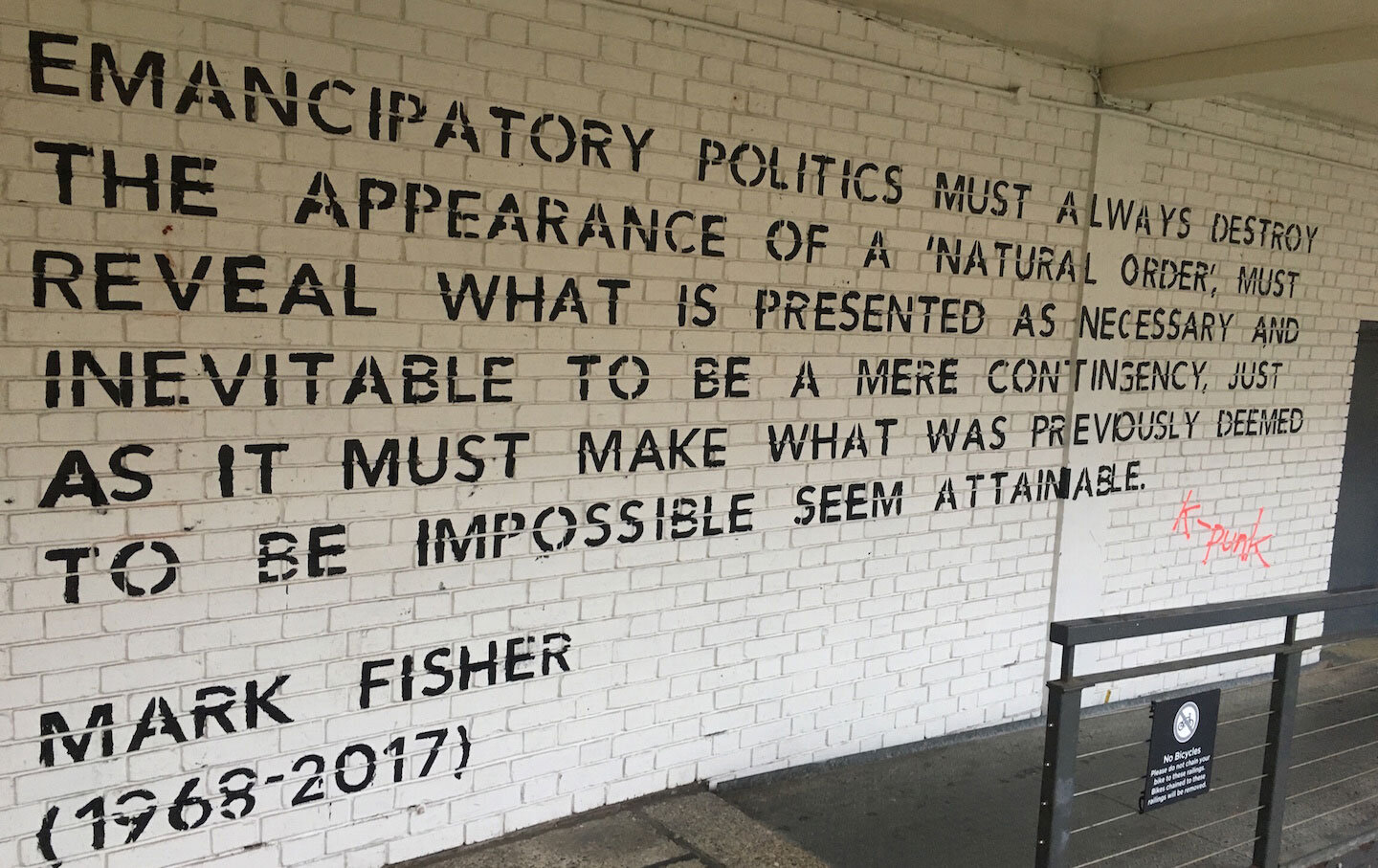

Mapping the Vampire Castle: An Analysis of Rhetoric and Concepts (Fisher's Ghosts, 5)

I’m noticing that this piece has retained a fair amount of popularity despite its age. However, I must note that it has a certain blindspot, especially relating to Mark Fisher’s thoughts on identity politics. I did a deeper dive at a later date, relating to his concept of Dis-Identity Politics that I would invite you to read: it’s a revolutionary approach that I think deserves greater attention.

※

I, of course, must start with at least one picture of a Vampire. It’s obligatory with this topic, so I’m going back and using one of the best: Max Schreck’s Count Orlock. The Vampire as thing-in-the-dark, plague-bearing rat-thing. This is not the sort of vampire that this essay concerns.

From where I’m sitting, it’s impossible to have an extended discussion of Mark Fisher without discussing “Exiting the Vampire Castle”. On New Year’s Day, I owned up to being a Fisherian, or a Fisherite, or whatever we’re calling people who draw from Mark Fisher – but the difficulty with this is “Exiting the Vampire Castle” because it is both some of the most insightful writing on the topic in question I’ve ever seen, and – in places – misses the point of the discussion altogether. Given this, declaring that you intend to talk about the piece is basically the same thing as loading a gun and pointing it at your foot.

Analyzing this piece is difficult for me: “Exiting the Vampire Castle” was my introduction to Mark Fisher. It seemed brilliant and insightful at the time. Now, it does not for a variety of reasons. I love Fisher’s longer works, but this essay is riddled with problems. The purpose of this piece is not to defend Fisher’s assertions (though I will be doing a bit of that, more due to rhetorical issues with the critiques than anything else,) but to try to recuperate some of what is valuable in the piece itself.

So, now that everyone involved is alienated, let’s get started!

I’m going to tell my niece and nephews that this was Nick Land. In all seriousness, though, I didn’t get a good chance to look at the potential interrelation I’ve previously noted between the “Vampire Castle” and what Neoreactionaries call “The Cathedral.” This allowed me to keep liking “Exiting the Vampire Castle”, because I find Nick Land et al. to be more irritating than anything else.

Some background: “Exiting the Vampire Castle” was a piece that Fisher published regarding what we tend to call “call-out culture” or “cancel culture” and closely related to the phenomenon I’ve heard referred to as “the circular firing squad” – the tendency of people on the left to attack one another on issues of purity and morality and history, instead of making common cause.

One of Fisher’s primary points of discussion is Russell Brand – who was in the news quite a bit around the time of the essay’s writing. At particular issue was Brand’s attitude toward women. You can watch him talk to Mehdi Hassan about it here (starting fairly late in, to get to the question at issue.) I want you all to take a moment to listen to Brand’s answer to that question, because I think a lot of the critiques of Fisher’s writing hinge on the idea that it’s not sufficient or honest, and Fisher takes it at face value (either out of ignorance or complicity, depending on the critique.) This is just the jumping off point, but I think it’s essential to keep in mind.

Fisher articulates that a particular “libidinal formation” has arisen that drives this practice, the “Vampire Castle”, which he describes by writing that:

The first configuration is what I came to call the Vampires’ Castle. The Vampires’ Castle specialises in propagating guilt. It is driven by a priest’s desire to excommunicate and condemn, an academic-pedant’s desire to be the first to be seen to spot a mistake, and a hipster’s desire to be one of the in-crowd. The danger in attacking the Vampires’ Castle is that it can look as if – and it will do everything it can to reinforce this thought – that one is also attacking the struggles against racism, sexism, heterosexism. But, far from being the only legitimate expression of such struggles, the Vampires’ Castle is best understood as a bourgeois-liberal perversion and appropriation of the energy of these movements. The Vampires’ Castle was born the moment when the struggle not to be defined by identitarian categories became the quest to have ‘identities’ recognised by a bourgeois big Other.

First note: the use of the term “identitarian” in this piece is a rhetorical misstep that we need to acknowledge to continue. Much as the use of “NPC” in our own piece on hourly labor (as being, roughly, being employed as a paid NPC,) we need to acknowledge that this term has been coopted by the right, and is used as a dog-whistle self-identification by racists.

You can thank Jacques Lacan for the idea of the “Big Other”. Image taken from Mark Fisher’s old blog.

Second note: The “big Other” described here is something that made up a big portion of his discussion of “really existing socialism” and “really existing capitalism” in Capitalist Realism. By way of explanation, the big Other is a convenient fiction to explain certain behaviors and beliefs. When “everybody” knows something, that is known by the “big Other” and if “everybody” believes something, that is believed by the “big Other”.

One of the main issues that Fisher raised with the VC is that “the sheer mention of class is now automatically treated as if that means one is trying to downgrade the importance of race and gender”, in short, he was describing the conflict between the identity-political strand of leftism and the Marxist strand. He then inverted this, noting that, in his view “the Vampires’ Castle uses an ultimately liberal understanding of race and gender to obfuscate class. In all of the absurd and traumatic twitterstorms about privilege earlier this year it was noticeable that the discussion of class privilege was entirely absent.” Note that Fisher doesn’t state that race and gender are unimportant, writing that “[t]he task, as ever, remains the articulation of class, gender and race – but the founding move of the Vampires’ Castle is the dis-articulation of class from other categories.”

He then proceeds to lay out various “laws” of the vampire castle, which he proceeds to illustrate. In his assessment, these laws are:

1) “individualise and privatise everything.”

2) “make thought and action appear very, very difficult.”

3) “propagate as much guilt as you can.”

4) “essentialize”

5) “think like a liberal (because you are one)”

For further information, please read anything other than Angela Nagle’s Kill All Normies, which is just things I already knew, but rewritten in a style meant to say that “both sides” are awful. When one side is made up of white supremacists.

In short, despite his terminology (which, to me, suggests a somewhat Catholic air to the whole proceedings), what he is describing is the adoption of a certain Puritanical-Calvinist attitude by the strand of leftism that is invested principally in identity politics. Far from being a uniquely Fisherian point – there’s a couple dozen lightning storms’ worth of electricity tied up in Tumblr discourse on purity culture – this is something that’s been commented upon many times, but before it actually got here, people were more enthused about it.

So what gives?

It seems to me that Fisher made several rhetorical missteps that opened him up to critiques. By using terms such as “moralisers” and “identitarian” he left himself exposed, and could be roundly critiqued on grounds of essentialism. If you instead read these words as stand-ins for “those who engage in moralizing behavior” or “those who are invested in identity” it becomes clearer. Those phrasings are clunky, and it makes sense to abandon them from a writing standpoint, if not a rhetorical one.

Let’s examine the rebuttals to this essay put forward by other writers. Let’s look, first, at the Medium post entitled “B-Grade Politics” by Angela Mitropoulos from the 23rd of November, one day after the original post. She accuses Fisher of “reinstating both an essentialist and identitarian understanding of class.” She is of course dealing with his statement that “the rejection of identitarianism can only be achieved by the re-assertion of class. A left that does not have class at its core can only be a liberal pressure group” – which is a fair reading, but which ignores how he states, early on, that “[t]he task, as ever, remains the articulation of class, gender and race”. As class is the one of the triad often left behind, it seems likely to me that he avoided mention of the other two later on to emphasize the importance of what has been left behind: class, gender, and race are the three things that he puts forward as being important, and ignoring the fact that he acknowledges this runs smack into the earlier quoted statement that “the sheer mention of class is now automatically treated as if that means one is trying to downgrade the importance of race and gender”.

Mark Fisher, image taken from his obituary in BFI. Part of depression is, no doubt, being able to see something inevitable coming and knowing that there is no averting or altering the event.

In short, Fisher predicted the main track that some of the most notable critiques would take, and pointed out exactly how it would happen, and they all went up days after his post, saying the exact same thing. Even if you wish to make these critiques of his work, from a rhetorical standpoint, you need to acknowledge that he already pointed out what you were going to say and attempted to address it. It’s telling that none of the major critiques quote from the early part, simply focusing on the rather Fisherian use of sensationalist and gothic language to frame the issue.

Let’s look at another rebuttal put forward by a site that republished as the original essay: Ray Filar’s 26 November rebuttal, “All hail the vampire-archy: what Mark Fisher gets wrong in 'Exiting the vampire castle'”. The subheading reads: “Where to start? He repeatedly accuses feminists of being ‘moralisers’, when he's not saying we're ‘vampires’ or ‘liberals’ instead. But there can be no real solidarity without intersectionality.”

Already, it’s not only a staunchly essentialist take but one that refuses to allow the possibility of class as having a place in intersectional analysis. But in all fairness, these subtitles are not often written by the actual writer and could be something other than reflective of their position.

For more information on the whole process of canceling, you can watch Natalie Wynn’s video on the topic, which is quite good, but significantly longer than I feel was necessary (one hour and forty minutes.) It can be found here.

Filar’s read of the Brand interview stops several seconds before Fisher’s, noting only the statement that “I don’t think I’m sexist”, but ignoring the culmination of Brand’s statement: “if women think I’m sexist they’re in a better position to judge than I am, so I’ll work on that.” This is not an absolution of Brand, but it is a step in the right direction: admitting one’s own shortcomings and promising to do better. He made the right move, so why not give him another chance to prove where he’s at?

Likewise, the author of the second piece talks about a point that Fisher makes late in the piece as “a queer insight of the kind that the Fisher condemns earlier in the article as ‘sour-faced identitarian piety foisted upon us by moralisers on the post-structuralist ‘left” - but misunderstands or omits the crucial point that the plasticity of identity (or identifications, if he prefers) doesn't stop people from experiencing oppression as if identities were essential,” which refers to a Fisher passage that reads, “The show was defiantly pro-immigrant, pro-communist, anti-homophobic, saturated with working class intelligence and not afraid to show it, and queer in the way that popular culture used to be (i.e. nothing to do with the sour-faced identitarian piety foisted upon us by moralisers on the post-structuralist ‘left’).”

Let’s try a third one. Let’s look at Matthijs Krul’s – a regular Jacobin contributor and a fellow at the Max Planck institute – November 27th piece. This piece, entitled “Gothic Politics: A Reply to Mark Fisher” seemed a bit more generous to Fisher, and perhaps consequently, seems to me to be a bit more well thought-out. It’s very much a remarkable piece, and I must quote some sections of it wholesale (these taken from about 60-70% of the way in.) Krul writes:

“[S]o much of the writing of poststructural and feminist theory has been about the body, its sufferings, and its agencies: because the adscription of identity is as much something one undergoes as it is something one does to oneself. Fisher in fact has already implicitly acknowledged this when he points out he is prone to forgetting he is male and white as ‘identities’: it is precisely this forgetting that the oppressed identities can never do, and that is what makes these identities salient in a political sense. If indeed the discourse of identity is the lackey of the bourgeoisie, it is not because of its self-awareness, but rather because it is simply a consequence of the reality of capitalist society. Its self-awareness, even when wrongly expressed, is a potent weapon against the invisibility of some forms of the reproduction and rule of this society – and thereby a weapon, however blunt at times, against the true lord of the castle.”

Finally – to avoid quoting even more large swathes of the article, I will summarize – we get to the assessment that Fisher lacks self-awareness regarding oppression. Mark Fisher was a white, male academic (granted, he worked at a continuing education college for much of his career, the equivalent of a community college in the US,) who worked as a commissioning editor for Zer0 Books (described, uncharitably, by Krul as a “left-wing vanity press”, though it has indeed declined in quality over recent years.) In short, by many metrics – race, gender, economic status – he was a privileged person.

Continental philosophers always look like Supervillains with lazy Public Relations departments. Still, Foucault is instrumental to understanding how our society constructs madness.

Privilege, it seems to me, is best thought of as “the right to forget.” The white person can “forget” about race; the man can “forget” about gender; the straight person can “forget” about queerness; the sane can “forget” about madness. And the wealthy can “forget” about money. But race will always be present for the ethnic minority; gender for the woman or nonbinary person; straightness for the queer person; and sanity for the mad person. Even if the mad person is “cured” (a dodgy phrasing, see Foucault for more,) they don’t become a default-state-sane-person; they become formerly mad. It seems to me that if an impoverished person is no longer impoverished, they retain the traumatic awareness of money and its lack. It is inscribed on the body, invisibly, in the nerves and adrenal glands, but it is inscribed.

While I feel that he made a number of mistakes in this piece, Fisher was right to point out that the disarticulation of class, and I feel like a lot of even the most well-meaning critiques completely fail to understand that class isn’t just how much money you have. Class status isn’t akin to race or gender, which Krul is correct to note are inscribed on the body of a person; it may be more akin to a mental illness. I understand Fisher grew up working class, so may have been free to forget that he was white or male in the privacy of his own mind, but he could never be free of the skinner-box anxiety.

Either William Gibson or Bruce Sterling said “Anything you can do to a lab rat you can do to a human being, and we can do almost anything to lab rats.” (Image uploaded to wikipedia by user Andreas1, under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.)

Because when you get down to it, that’s what a privilege is: it’s the right to forget about something like race or gender, to occupy the empty default of just being normal or regular. A woman or a member of a racial minority is always reminded from the outside that they’re different, robbed of being “regular” on one or more axes.

The member of a lower class or working class, as well as the mentally ill person, isn’t reminded from the outside that they’re different. They have been conditioned to be unable to take that position, robbed of the ability to step into the role of “regular” without some sort of aid.

Note, this is not to say that a person can’t be both poor and a woman, or mentally ill and black or latinx, or any other combination of these factors of race, gender, and class: but these mechanisms of oppression, despite being interlocking and coextensive, function differently, and I’m not sure a comparison can be drawn between them except by analogy.

Class has many dimensions, principally economic, but also geographic and cultural. I’ll probably discuss that some other time, but I will point out that the widespread disavowal of class as a concern has led to a scarcity of productive discussion and vocabulary about it: if the people concerned with issues of identity politics could take up productive analysis of class, I feel that the world would be a better place for it. I feel that this is what Fisher was trying to encourage, but I also feel that he failed to communicate that effectively.

Don’t believe me that Lovecraft was racist? Google his cat.

A major part of this, I feel, is tied up in Fisher’s aversion to everything American, which is not shared by many of his critics. While I don’t think him racist, I feel that race is a blind spot in his writing, best evinced by the fact that he failed to touch on race once in his piece in The Weird and The Eerie on Lovecraft: it is impossible, I feel, to have a productive discussion of that writer without acknowledging that he was a racist, because it’s a through-line of the man’s work, and while the piece on Lovecraft is the best writing on Lovecraft I’ve ever seen that failed to acknowledge race, I still feel it’s weakened because of that.

To the best of my understanding, British culture is incredibly preoccupied with class to the same extent that American culture is incredibly preoccupied with race: discussing it is impolite, and people who do so are obsessed with the subject. This is despite the fact that it is an engine of oppression that runs rather noisily in the basement, knocking from beneath the floorboards like an off-balance washing machine.

Perhaps if I repeat the technique I used in my piece on the Weird, where I yoked Fisher to the author China Miéville (I am consistently surprised that I don’t find more material that does this, as both are Britons of a Marxist bent with a penchant for the weird, they seem a natural fit for one another), something useful might fall out. For this, let’s use the piece “On Social Sadism”, written at a similar time on a related topic.

I think that this essay can be used as a way of offering another explanation of the problem that Fisher discusses in the piece:

Consensual peccadilloes are not at issue here: this is about social sadism – deliberate, invested, public or at least semi-public cruelty. The potentiality for sadism is one of countless capacities emergent from our reflexive, symbolising selves. Trying to derive any social phenomenon from any supposed ‘fact’ of ‘human nature’ is useless, except to diagnose the politics of the deriver. Of course it’s vulgar Hobbesianism, the supposed ineluctability of human cruelty, that cuts with the grain of ruling ideology. The right often, if incoherently, acts as if this (untrue) truth-claim of our fundamental nastiness justifies an ethics of power. The position that Might Makes Right is elided from an Is, which it isn’t, to an Ought, which it oughtn’t be, even were the Is an is. If strength and ‘success’ are coterminous with good, what can their lack be but bad – deserving of punishment?

Meanwhile, liberal culture wrings its hands over the thinness of the veneer over our savagery, from the nasty visionary artistry of Lord of the Flies, to lachrymose middlebrow tragedy-porn, emoting and decontextualising wars. These jeremiads beg for a strong hand, for authority, to save us from ourselves. A state, laws. As if those don’t – and increasingly – target the poor.

China Miéville never looks like he wants his picture taken, I’ve noticed. It’s always something he’s at least vaguely upset about.

Here, we have the two-pole system of the dominant discourse: the one glorying in sadism as necessary, the other lamenting that it is the same. I feel that the second is easily mapped on to Fisher’s Vampire Castle, though with a bit of work.

What Fisher calls the Vampire Castle could be an internalization of what Miéville calls the “civilising process”, it springs from a desire to paint a veneer over a perceived savagery, to repress it. While the motives that Fisher discusses – to excommunicate, to correct, or to exclude – definitely seem to be present in some circles (see: a lot of internet discourse), Miéville might argue that they are secondary, that they are symptoms of a root cause.

That root cause is the aforementioned “social sadism”, but it is a cathected, redirected sort of social sadism. It’s an attempt to bend the flow of cruelty back on itself, which it does, but messily.

Later on, Miéville tries to discuss a way to move past this:

None of which is to say that socialists shouldn’t strive for a politics of radical empathy. Not cool calculation; not realpolitik; not, in extremis, necessary ruthlessness; nor our earned hate, obviates that. Indeed hate, unlike contempt, presumes empathy. An empathy which can check what surplus hate might provoke.

But the vocabulary for what needs to be discussed is lacking. This section – entitled “A Harder Battle” – is very much like what many people understand Fisher’s Acid Communism to be about, and that will be a valuable discussion in the future, but that is secondary to the purpose of this piece.

So, unsatisfyingly, I come to my conclusion, and I will close of my discussion of Mark Fisher’s unpopular gothic-revolutionary “Exiting the Vampire Castle” with an analysis grounded in a different Gothicism: I feel that the piece is not akin to a vampire, but to a Frankensteinian monster, an attempt at something daring and potentially revolutionary, but which got away from its creator, and through its effect on the world and on him, it led its maker into a cold and lonely place, from which he did not return.

※

Postscript: I feel there is no real way to finish this within the limits I’ve established for myself, so instead I’ll toss some attention to someone doing a good job of discussing the same concepts (albeit not in an explicitly Fisherian vein,) and give a shout-out to Ellie Kovach over at You Don’t Need Maps who wrote a very good piece on cancel culture and identity politics.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference.