Solidarity in the Time of Coronavirus

wooo, spring break. (Image from ALFRED PASIEKA/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY, taken from New Scientist.)

I’m on Spring Break this week, so I figured I’d go back for a bit to the twice-a-week schedule. Part of this is that I wanted to announce that we’re releasing a book on the 21st! Keep your eyes peeled for more information, but it’s one I’m very excited about. The second reason is that I had a lot of thoughts coupled with the opportunity.

So between Edgar and I there are three public-facing jobs, and we live in the Kansas City area, which recently saw its first case of Covid-19. Needless to say, I’ve been feeling a fair amount of anxiety about this. Not for myself: despite everything else, my immune system is reasonably strong. But we live fairly close to my parents (I go over to their house once a week and use their laundry facility and do any tasks around the house they need done,) and I’m worried about passing it on to them if I do get infected.

Because, you see, the disease is potentially deadly to people in my age bracket, but people in theirs are at much, much greater risk.

The recommendation being fielded is that, if you have the virus, you should get tested. If it comes back positive, you should isolate yourself for two weeks. Of course, there’s a presidential primary on – Missouri votes tomorrow – and I can’t afford to miss work. You can’t exactly work a retail job remotely.

It occurs that there’s no private sector solution to a public health problem. Diseases spread through populations, and so it requires a response at the scale of the population.

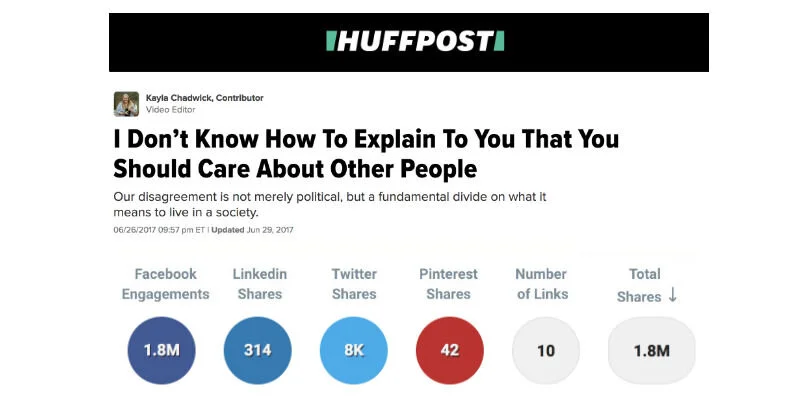

This is my attempt to do what this Huffington Post commentator failed to do — an article which, admittedly, I think kind of approaches things in a somewhat bad-faith fashion.

So I wanted to present, for those people out there who don’t understand that they should care about other people, the rational-self-interest case for why things like paid sick days should exist.

You know the sort of people I’m talking about. Those among our friends or neighbors who say that they don’t want to pay for anyone else’s healthcare or similar. They say they pay their share and that nothing else should be asked of them.

I disagree with this position, but I don’t think the argument is being made in bad faith. I do think that it’s based on faulty premises, but I’m not about to say they’re necessarily bad people because of that. On one condition: if you hold this position, that you should be allowed to “secure that bag”, you can’t hold it against other people for doing the same.

This should be an uncontroversial corollary: in my opinion, no ethical system that has asymmetry built into it seems worth considering.

This means that it isn’t permissible to prevent someone else from getting their fair share. Knowingly infecting someone else with a virus that’s going to knock them on their ass is as unacceptable as saying that someone shouldn’t be able to work and get the paycheck they’ve agreed to work for.

(Again, there are some issues with this that I am leaving aside for purposes of discussion here.)

Do you have any idea how much bacteria, cocaine, and fecal matter is on the average bank note? And that’s not even getting in to the hand-washing standards of the average men’s room.

In the service industry in America, there is a culture of not taking days off: it forces others to pick up your slack, and it cuts into your own paycheck. It hurts the group, and it hurts yourself. The people handling your food, the people working the cash register, the people stocking the shelves have both economic and cultural obstacles to taking time off.

These are also the people who are most likely to come into contact with an infectious disease.

This set-up is also why infectious diseases spread in America like wildfire.

With a frightening looming epidemic like Covid-19, it is not these people but this culture that will result in the infection spreading.

Think about it: you order a pizza, and there are three people who are not just culturally discouraged but strongly economically discouraged from taking time off. Many of these people are in the demographics that are at lower risk from the disease: they are not prevented from working by their health – it is consideration for others that would make them stay home.

If we can’t reasonably prevent them from working, and can’t reasonably let them work, then we have a paradox. It’s a Catch-22.

This article from the BBC was one of the few talking about face masks that didn’t have a dog whistle quality to it. So…yeah.

The only possible answer is to think beyond the current moment. The best thing for everyone is if this person doesn’t have to be expected to work while they’re sick, and shouldn’t be expected to put themselves in the poor house doing the right thing.

Now, you might argue that unscrupulous people might take advantage of this. Clearly, the proper answer is that a worker taking a sick day might be required to get tested. At the current moment, testing costs more than $3,000 dollars – or slightly under one-fifth of a full-time minimum wage worker’s years wages after taxes. This fee represents a barrier to the worker doing the right thing, meaning that it won’t be used, which means that the disease will spread.

The only possible reasonable answer here is to lower the cost of the testing. Perhaps, because it benefits everyone in the society, everyone in the society should pay a portion of the cost, whether they are tested or not. After all, if it leads to the quarantine of infectious individuals, then the uninfected benefit: they remain uninfected. Keeping this same infrastructure in place in the future will prevent – or at least discourage – this situation from emerging again.

What I’m dancing around here is that everyone should have paid sick days and there should be some kind of public health care. This is based on old adage that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. That is, preventing a problem from emerging is better than dealing with it after the fact.

This wisdom is lost on many Americans. Many of us gamble on the solution never being needed. There are 300+ million of us, the chances of us getting the disease are low.

Based on demographics, sure, but if it means death, it seems like it shouldn’t be something that we risk.

The fact of the matter is that there’s no such thing as a closed system. You can say that you’ll not eat out, you’ll work from home, you’ll cook all your own meals with delivered produce, handle all necessary transactions with credit and debit cards and bank transfers.

But are you disinfecting your mail? What if you get called for jury duty? What if your roof develops a leak? What if your phone breaks? What if a thousand and one things go wrong?

Doesn’t all of this sound exhausting?

Why not just keep it from being an issue?

Because the best way to take care of yourself is to take care of those in your community. And your community is everyone, including the people who make your food, work the cash register, and stock the shelves.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference.