In the Empire of Empty Ghosts: On and Against the Emerging New Dualism (Odd Columns, #8)

I've been talking trash on Rene Descartes longer than I have Francis Fukuyama, and I've got a whole tag about dunking on Francis Fukuyama. Most of this stems from a class I took in college about Phenomenlogy that was deeply interesting and effecting, which had a thread of skepticism towards Cartesian dualism. The basic problem is with Cartesian doubt, and the inadequacy of Descartes's solution to it: the logical endpoint of the argument is solipsism, and he didn't want to go there, so he invoked the God of Christianity. A more responsible way to approach issue isn't to just wave the problem away but to step into it and investigate its underpinnings.

If you don't want to be a solipsist, maybe look at why you question your perceptions of the world to begin with. Perhaps there's a problem there. What do you get from questioning your perceptions of the world? Comfort, perhaps, when you're wrong. However, it has little to no predictive power: it requires that you question everything, even the things that work. This is an uncomfortable position, and we lose nothing if we assume that our perceptions reflect something in the world around us.

As a byproduct of this, I'm very skeptical about the dichotomy at the root of this dualism, between mind (or spirit) and matter. I didn't study philosophy deeply, during this period of my life, I studied psychology (as a minor. I majored in English, hence why I'm an English teacher,) and it wasn't easy for me to shrug out of the more materialist stance that was imparted to me by this discipline: the actions of the mind, while not wholly explainable by conditions in the brain, are deeply effected by them. I'm a Traumatic Brain Injury survivor – I know this firsthand: I had an experience in my earliest youth that required that I remap my whole brain, and I still have a bit of a mutant epistemology because of it (primarily, or at least largely.)

Skull and brain illustration, taken from wikimedia commons, originally done by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 License 2006.

Because of my experiences, I believe that there's not simply a physical dimension to the mind, but that there's a biological dimension to he mind: it's not just material, but it's material and wet, rooted in the mass of fat and nerve endings that floats behind your eyes, among other things. This isn't to say that I'm wholly hostile to the idea of something more ethereal or abstract, simply that I do not view it as being a complete explanation for the mind.

This is a bit of a long walk to get to my point: the Cartesian dualism between mind and matter, or matter and spirit, is dead outside of the fact that we still talk about it. It informs our discourses, but there is a new dualism that people operate under that we leave unspoken. I wanted to talk about this dualism and describe it, even though I don't personally view it was any more useful or meaningful.

Let's examine the old one for a moment. I'm going to simplify: spirit and matter. In the older conception, spirit was an ethereal principle that was associated with vitality and meaning, the obsession of the romantics and the spiritualists. The thought was that a person was their spirit, the ghostly thing that inhabited the inert matter of the body like a hand in a puppet.

Matter, on the other hand, was the inert, weighty thing that composed the majority of the world. It was solid, and had substance. Matter, however, was also meaningless unless it was somehow acted upon or somehow impregnated by spirit. It was very much the junior partner in the spirit/matter duality, viewed as less important and more liable to be dismissed.

I stress, this is simply the view that held true for a long period in so-called “western civilization” – I don't know enough to speak of how it's viewed in indigenous, aboriginal, or east Asian cultures. This, however, is the view that I see promulgated by Descartes, and which is definitely the case in Victorian and Post-Victorian Anglo-American culture.

The solid and the ethereal, though, have traded traits, and the result is something new and unfamiliar.

We no longer have the “spiritual” and the “material” – I would argue that what we have is the “informational” and the “totemic”.

When I say “informational” I refer to an ethereal principle that is incomprehensible to the human mind without extensive training. The binary bits and bobs that are fired around the world at amazing velocities through all-to-material infrastructure and more and more come to determine the outcome of human events (through things like algorithmic sentencing, the finance system, social media, and the like.) It cannot be directly touched, and has a materialist priesthood attending to maintaining its infrastructure and handling it as a means of value-extraction. It's packets of information that are meaningless to the human mind.

When I say “totemic” – and I use “totemic” in the most general anthropological sense – I refer to the material objects that have taken on a significant and personal relationship in human affairs. You see this in the way that some people personify their cars, naming them and treating them as living beings. You see this in the fetishization of analog photography and music. You see it in anything described as “vintage”.

Think: around the time that social media became popular is when the “hipster” began to appear. When the simulacra became complete, the subcultural longing for the genuine and the authentic became notable. Of course, it was nascent in earlier cultural moments: the parallel lionization of the “real” in both suburban American and hip-hop culture, the longing for some unquestionable essence. This only became truly important to people when the world became measured and known and parceled out. The original was made into a fake version of itself, and the presence of the fake produced a longing for the real.

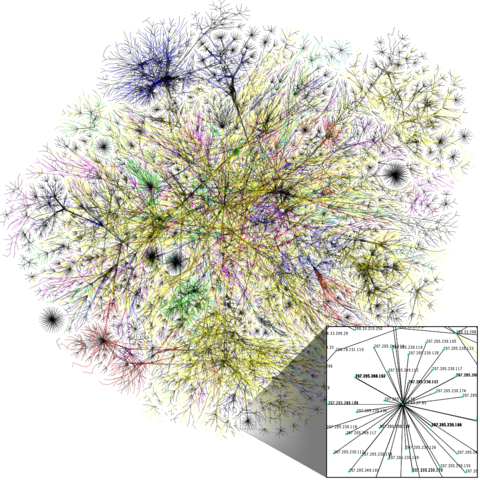

Data visualization of the internet from the Opte Project, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license on wikimedia commons.

Informational reality is the product of measurements and measurements of measurements. It's discourse divorced from the human mind and tongue, three or four moves deep in a progression away from the supposedly natural world that we perceive. As computation increases, there is an exponential increase in the amount of information dealt with. This most likely out-of-date article from LiveScience from 2016 said that there was about 1 Zettabyte of information on the internet, and they predicted it would hit 2 Zettabytes by 2019. A Zettabyte is 1x1024 bytes – if it was converted into unicode characters, and then assuming an average length of four letters per words, this would be about 32 octillion words – approximately equal to 118 quintillion copies of Ulysses worth of words (that's 247 quintillion pounds worth of book, since I've got my calculator open.)

There is no way that all of this information passes in front of human eyes or produces a bloom of meaning in the human brain. The primary purpose of this information is to be read by machines and not to be intelligible to anything alive. It is, in short, inhuman information that we only deal with in aggregate.

This is the spiritual principle of our age: orisons, curses, evocations, and conjurations encoded in patterns of electrons and photons. It's unquestionably material, but invisible to an unassisted human. It may as well be the actions of a friendly (or not-so-friendly) poltergeist for all we can tell.

At the same time, our cultural fascination with the solid and material, the elements of the bygone age of solid technology with switches that audibly click into place with a tactile snap has increased. Consider how much contemporary horror fiction relies upon the trappings of analog technology: glossy photographs, tube television, VHS cassettes, as well as rotary and touch-tone phones all feel numinous, as receptacles for the spirits of an age even further removed from our own than they are.

I view all of this as connected: the emergence of a world-encircling network of information, capable of delivering such immaterial goods as music and movies at will is paired directly with the return of music on vinyl and analog photography. The temptation is to assume that the former produced the latter, but what if both are the product of an implicit shift in ontology? If spirit is emptied of meaning and becomes the machinic discourse of information, would it not make sense that the material goods of older ages would come to seem ensorcelled and haunted? After all, information can be reproduced endlessly with minimal loss to the original, but an analog camera, even if it's one of ten thousand, comes to become a magical item: a device that could, conceivably, produce images without the intrusion of a larger infrastructure. Likewise a vinyl record can produce continuous music, reproducing dead voices with a fidelity greater than the human mind can perceive (see the mention of the Oliver Sachs book in that link for more detail.)

It all makes sense.

Of course, it's also all bullshit.

I mentioned that I've got a materialist bent, but this doesn't mean that I deny that other things might exist. I don't know what the foundational substance of the world as it is given to us is – it may be material, it may be otherwise. I tend to dodge the question altogether, because I'm more interested in what it all does – after all, my mantra in these writings is “a thing is as it does” not simply as a functionalist dismissal of questions of identity, but because my orientation is towards becoming, not being.

What does it do? What's it for? Why are we looking at this?

The Marea cable, going from Virginia to Spain, weighs 10,000,000 lbs. It’s integral to the internet and incredibly physical.

When you get down to it, these analog devices achieve their special status because of how we use them and how we think of them. They're devices made for human hands by human minds – and the informational substance that I've contrasted them with is the exact same: it's simply that there's a few steps of removal between the fog of data and the phone that you may be reading this on. When you get down to it, the internet and other such infrastructure has an amazing physicality to it: you put things in the cloud, but the cloud is hosted in a data center located somewhere relatively out of the way, where land and utilities are cheap, and it's parked there indefinitely, taking up a miniscule but measurable space on a physical disk in a physical device in a physical building.

It only seems immaterial because we have pushed the infrastructure to the margins and do our best not to think about it unless it breaks, and the envelope of information unfolds and we're left with the world of spirit and matter, or spirit-matter that we've lived in all along.

My perspective is that ontologies of being are fundamentally more useful in today's world – questioning not what people or things are but how we relate to them. I feel that now, at this point where we are transitioning from the dichotomy of matter/spirit to one of information/totem that now is the time to give up questions of being and focus on how things actually work.

Not just because it's a better approach, but because, when you get down to it, dichotomies are not just less useful but less interesting. When categories are solid and permanent, there is a tendency to simplify down to just two categories, and this primes us to see things in dichotomous terms. This is why the gender binary exists, this is why we talk in terms of order and chaos, good and evil, dark and light, master and servant.

The dynamics of the world as it really exists are much stranger and more complicated than all of this. Our situation is such that our old modes of simplification just aren't going to cut it.

We need to embrace complexity if we are to survive and thrive in the world that is coming to be.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates, and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference.