Edgar's Book Round-Up, March-April 2021

Christ, there’s always so much work to do, and so much weather to contend with (it snowed the other Tuesday and it’s already been hitting 80 Fahrenheit pretty reliably), and just… So much. All the time. Anyway, I’ve been reading a bunch of books to try to make sense of it and/or get away from it, so here there are. As of this post, links should go to our Bookshop; if you plan to buy some, consider doing it through them. We get a kick-back and you support the indie bookstore of your choice. If you’re local, consider selecting, or purchasing directly from, the Raven in Lawrence, KS, or Wise Blood in Kansas City, MO.

※

We begin this round-up with a book I wasn’t necessarily planning to discuss, since I read it at my therapist’s behest and I don’t like to admit that I occasionally read a self-help book. But honestly, The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk isn’t so much a self-help book as it is an interdisciplinary work of nonfiction, useful to professional and layreader alike.

The Body Keeps the Score in several languages, from the author’s website.

Van der Kolk is past master when it comes to the study of trauma, and the many ways it impacts people’s lives. From the start of his career, working at a VA hospital in the wake of the Vietnam War, to today (or at least, the time of the book’s publication), he’s seen pretty much every kind of emotional and physical trauma people can experience. From self-destructive veterans to near-catatonic children, if it’s the result of trauma, he has probably dealt with it, and helped others deal with it, too. He’s also pushed for the inclusion of something like what I’ve heard referred to as Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for years — to no avail yet.

But van der Kolk’s bona fides aren’t the star of The Body Keeps the Score, though of course, they inform it. The surprising allure, for me, was van der Kolk’s ability to almost seamlessly weave together elements of psychiatric history, biography, case study, and cultural analysis to discuss the pervasive traumas of the late 20th century, and then to lay out a variety of treatments, most of which are grounded in bodywork as much as in conventional therapeutic interventions, that have been shown to be effective in treating the aftereffects of trauma and traumatic experiences. The broad scope of the work could have become overwhelming, but it never does: van der Kolk has an eye for the cinematic detail, the compelling personal history, and the surprising twist that keeps the book engaging and, often, almost thrilling. Not to oversell it, but the last nonfiction work with implications this far-reaching I read was After Babel — both struck deep chords in me, and I’ve been imploring most of the people I know to read both of them for some time now.

The next two books I finished, A Darker Shade of Magic by V. E. Schwab, and Stormsong by C. L. Polk, will be discussed later, with their respective follow-ups, which brings us to The Office of Historical Corrections by Danielle Evans.

The cover, via Amazon.

I picked up this collection, comprised of several short stories in addition to the titular novella, at the recommendation of a friend, and admittedly, it falls a little outside the speculative fields I tend to prefer. I’ll admit, I was at first unsure — but maybe halfway through the first story, I was no longer worried. Evans’ literary style, coupled with an approach to story construction that reminds me of none other thank Kelly Link (a more-or-less life-long favorite of mine) sold me quickly on the collection.

The stories range in theme and setting, though most are roughly contemporary, and roughly focus around the complexities of modern relations — between women, women and men, and about race. But of course, these are some of the bread and butter of contemporary literary fiction; where Evans surpasses much of what I’ve read in the genre is her dreamy ability to weave past and present together, to present a situation and offer, in place of solutions, a dangling question, an ellipsis laden with implication. Many of her stories end in the moment before or the moment after a decisive action, leaving the reader to consider what might happen next, or what should happen or should have happened already, the stories offering no easy answers, and no absolution for those who seek to look away. The collection has been highly-lauded by organs more prestigious than this, and I have to say: it thoroughly deserves the acclaim.

The cover, once again via Amazon.

The next book I finished was Robin diAngelo’s White Fragility, mostly because the first few chapters were suggested as pre-work for a series of diversity, equity and inclusion workshops at my job, and by the time I’d read the assigned part, I was over half-way through it anyway. While diAngelo’s place as a racial-equity advisor, and by extension, the book’s utility, has been called into question, her writing is unquestionably solid. She offers useful examples, both from her personal experiences and from her workshops, of what white fragility is and how it serves to center whiteness in discussions of racial equity, and does so in a very approachable way.

Is it an end-all be-all? No, and it’s certainly not a stopping place in antiracist reading. But it is a capable introduction to the topic, and offers some frameworks for thinking about, especially, anti-Black racism in the American context. Basically, it’s an introduction to thinking about racism for white people, and as such, it felt pretty accessible. That said, I’m hoping to get my hands on Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, which I understand is much more in-depth and examines not only the state of things with respect to the American white supremacist society, but also how it got like that.

But this brings us to Soulstar by C. L. Polk, the phenomenal third book in the Kingston Cycle. As I mentioned previously, the first installment of the trilogy blew me away. It’s been a long time since I read something and thought, “I wish I’d written this”; it’s been even longer since I dragged my feet on the last book in a sequence because I didn’t want it to end: both of these came to pass in the course of reading Soulstar. Where the first book covered the revelation of a deep-seated social inequity, and the second book covered attempts to rectify it through conventional means, this third book takes a thoughtful and clear-eyed look at a moment of multifaceted revolution, the characters seeking to avoid heaping even more suffering on those already ground down.

The covers of all three books, in a photo I took because I was so excited about them I had to gush about them on social media and you need pics for attention.

Polk’s approach to social change is, as mentioned, thoughtful and intense — they remarked that, in spite of an affection for the romance of monarchy, that affection was at cross-purposes with their own political views, which guided the course of the series — but the politics of the thing would be adrift without compelling characters and a richly-built world. And Polk more than delivers, on both counts: much like Yoon Ha Lee’s ever-deepening setting in the course of Machineries of Empire, Polk establishes something that feels like an Edwardian-ish gaslamp fantasy in Witchmark, only to continue to draw out the implications of the setting from there, into territory that is simultaneously much richer and much stranger than it at first seemed. And the characters both the icing on the cake and the meat of the story: Witchmark and Stormsong followed the Hensley siblings, two scions of Kingston’s uppermost class, as they revealed and came to terms with the sins of their father (who is a real fucking bastard, not to put too fine a point on it); Soulstar follows Robin Thorpe, introduced in Witchmark as a nurse at the veteran’s hospital where Miles, the estranged son of the Hensley family, works. But where Miles and his sister, Grace, are hopelessly entangled in the familial web of Kingston’s upper echelons, Robin is not — and it is Robin who, ultimately, is able to begin to rectify the sins of the past.

Of course, she’s also doing this while trying to reunite with her long-lost spouse, and that’s the other side of Polk’s genius here: against this backdrop of political instability and social upheaval, Polk forwards deeply, tenderly queer love stories. Be it Miles, falling swiftly for Tristan (beautiful, mysterious, magical), Grace seeking to pursue Avia (fiery, passionate, class defector), or Robin, gently rekindling her relationship with her spouse (traumatized, brilliant), Polk’s eye for the details of the beloved and the lover both are really perfect. I often find myself put off by too much romance, but in the right hands — like Polk’s — I found myself yelling internally for the characters to kiss already, good god. And the twin engines of the plot combine in a way that felt very, very real. I cannot speak highly enough of these books, and I am very excited to get my hands on more of Polk’s work.

The UK cover, via its publisher.

The next book I finished was another assignment from my therapist, Breath: the New Science of a Lost Art by James Nestor. As a single-topic piece designed for a popular audience, it’s quite good: Nestor frames his research with his own involvement in a test designed to see what, if any difference, there is in quality of life based on breathing through the mouth or through the nose. At least anecdotally, it seems to be pretty substantial, and this provides the springboard for Nestor’s thesis — we’re all breathing wrong, and it’s fucking up our lives.

Needless to say, that’s a pretty broad claim. It’s clear that Nestor has done his research, citing classic texts on yoga, contemporary studies of many kinds, and, of course, personal experience and interviews to support it. And he brings a sense of humor to the proceedings: in discussing the jaw-strengthening techniques of “Mewing” exercises, he does note that doing so makes the person doing it look like they’re about to hurl. But, like many contemporary pieces on health and well-being, Nestor’s writing is plagued by sweeping generalizations about “ancient times” and “long-lost arts” (hell, the latter is right there in the title), a rhetorical crutch that sets my teeth on edge (and is discussed, in a slightly different context, in this piece, for which I offer a CW: diet talk). It was, nonetheless, interesting, and I’ve definitely found myself self-consciously breathing through my nose more, so there’s that, I guess.

In any case, right after that, I got sucked into Martha Wells’ much-lauded Murderbot Diaries. Here is where I finished the first one, but I’ll discuss them as a group later. This is also, however, where I wrapped up the audiobooks of Patricia C. Wrede’s YA classics, the Enchanted Forest Chronicles.

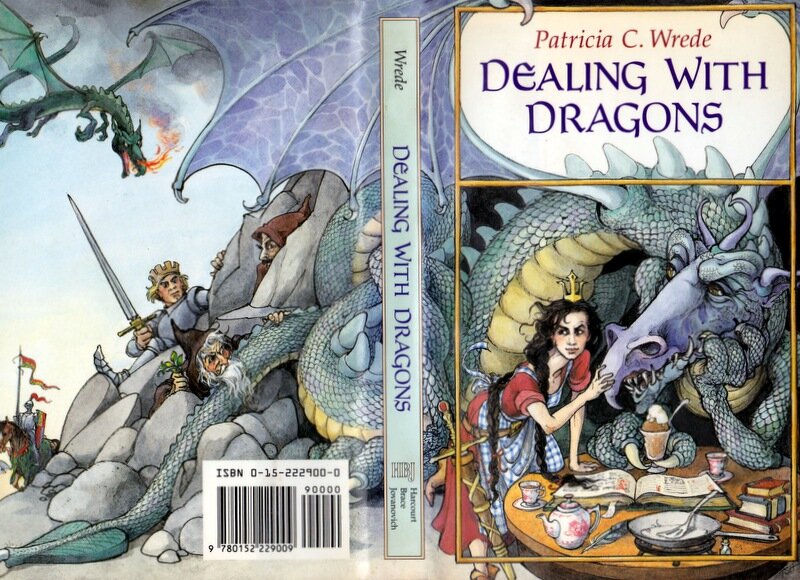

I read and reread Dealing with Dragons, the first book, when I was a child, and I think I made it through the second installment, Searching for Dragons, at some point. Look, I like dragons, and Princess Cimorene, the central character, was very compelling. She still is: engaged to an obnoxious princeling in the first book, she runs away to become a dragon’s princess, and is taken in by Kazul, a misanthropic but largely genial dragon who mostly wants someone to make strawberries jubilee for her. Cimorene is amenable, and being a dragon’s princess is a good way for her to get out from under her family’s expectations and do what she wants: study magic, practice swordplay, and cook. As the novels progress (though apparently the fourth one was published before the others, which is a bit of a mindfuck for me), Cimorene makes friends, gains agency, and melts evil wizards with soapy water and lemon.

The full-wrap cover of the first book, which I share here because I love Trina Schart Hyman and will take any opportunity to share her work, and which I found at this lovely review.

Frankly, it’s delightful, if unchallenging to the adult reader: exactly the kind of good, clean fun that I think was largely expected from YA fantasy at the time. And while the novels lambast a lot of broader swords-and-sorcery tropes (while also reproducing some shitty ones — a side character’s name features the g-slur, for example), it also subverts a number of them. When others dismiss princesses as being “silly,” Cimorene often points out that they’re taught to be, and given no other option; while Cimorene herself is not a fan of courtly etiquette and needlework, her own twin affections for cooking and swordplay provide a richer foundation for her character. They’re fun and light-weight — and absolutely full of dragons, which is always a selling point for me.

The cover, via Amazon, to which I am not linking ‘cause fuck ‘em.

I followed these, or rather paired these finally (I tend to read multiple book simultaneously), with something a little more serious: Han Kang’s fraught and, often, frightening thriller, The Vegetarian. The story follows Yeong-hye — or focuses around her, rather, since the three sections of the book are narrated by her husband, her brother-in-law, and her sister — as, in the wake of a series of troubling dreams, she forswears all animal products. This wreaks havoc on her life on every level: her marriage, loveless and rote, collapses; her parents refuse to speak to her; her brother-in-law suffers a nervous breakdown; her sister is, finally, left to care for her as her health spirals downward.

I’ll admit, I was a little caught off-guard by how intensely and intimately the story focused on what rapidly transpires to be Yeong-hye’s severe eating disorder; having flirted with disordered eating for most of my life, it was often on the triggering side, and potential readers should probably be more aware than I was. That aside, Han Kang has drawn a truly compelling, even fascinating, portrait of a woman bound up in others expectations and desires and ideas about her being, and Yeong-hye’s quest to escape this binding is impossible to look away from. The rest of the family, too, is drawn with depth and a sort of grim empathy: their own blinders and drives are just as richly-mined as Yeong-hye’s own, and the shifting narration lends energy to the plot. Well-received on its appearance in the English-speaking world (this write-up in The Guardian is pretty exemplary), its translation by Deborah Smith seems to be ripe for discussion, to put it mildly. In any case, it certainly earned its acclaim, and I hope to read more of Han’s work (probably in Smith’s translation).

Got another Murderbot Diary in here, and then The Rage of Dragons by Evan Winter. I’ll say more about Winter’s fantasy epic when I’ve finished the second one, which will probably be in the next round-up, but I do want to take a moment here to encourage anyone seeking out a really, really, really good fantasy bildungsroman, revenge-flavored, to seek out Winter’s Burning series. It’s great. And, of course, there’s dragons.

Which brings us to Talia Lavin’s Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacy. Covering much the same territory as my beloved Neoreaction a Basilisk, as well as Dark Star Rising by Gary Lachman, which Cameron read a while back, Lavin charts how various, largely-online subcultures — pick-up artists, TERFs, et alios — draw people into white supremacy as an over-arching web of horror. But where Sandifer works in a philosophical mode, charting the ancestry of the beast, Lavin is a journalist at heart, interested less in where contemporary white supremacy originated and more in its current propagation — and, of course, seeking to prevent it.

The cover, from the TLS bookshop (but you should get it from ours, actually, if you’re ordering it.)

I didn’t really expect to learn anything I didn’t already know from Culture Warlords, but I’m chronically online and have Seen Some Shit; I vividly remember inadvertently arriving at a neonazi website in my late teens and nope-ing right the fuck out of there. And one really doesn’t have to be from the internet to know that there’s all kinds of awful things out there. But, to borrow Sandifer’s analogy, it’s a basilisk, and Lavin — noted sword-owner that she is — came to fight. With snark and aplomb, Lavin chronicles her activities undercover on the far-right web, catfishing Ukrainian white supremacists and infiltrating incel boards (where, weirdly, “Mewing” came up again), but also more public activities, like being chased from a “free speech” colloquium that hosted the public faces of racism and misogyny, or visiting Charlotteville in the wake of the Unite the Right rally. And even if Culture Warlords brought me little that I didn’t already know, Lavin’s explanations of how and why people are drawn into the vortex is clear and charming (if a little prone, as many books partially composed of essays published elsewhere are, to occasional repetition). It’s exactly the book I’d want on hand if someone who isn’t terminally online needed a breakdown of the situation.

Burned through another Murderbot Diary in here — I promise I’ll actually talk about them at some point — and thence to A Gathering of Shadows, the second book in V. E. Schwab’s Shades of Magic series. The first one, as mentioned above, received a fair bit of hype on release, and the second one is a worthy successor. Although the third one came out in 2017, my library’s app doesn’t have a copy yet, and given my mixed feeling son these two, I’ll take the time to discuss them now.

Here’s a box set of all three, once more from Amazon and with the caveat that I haven’t read the third one and it’s not super high on my priority list.

The series largely focuses on Kell, who is an antari, one of the few remaining magic users with mastery over all four alchemical elements, as well as the ability to travel between worlds. There are four Londons, in this setting: Black London, long ago consumed by the raw force of magic; White London, from which the magic is draining as its people scrabble to gain as much power as possible, and cling to it with raw force; Red London, whence Kell hails, and where magic is everywhere, but also carefully held in balance; and Grey London, which maps roughly onto our world, circa the early nineteenth century, and where we meet the deuteragonist, thief and scapegrace Delilah Bard. In his role as emissary between the various Londons (except for Black London), Kell is given a powerful magical artifact which could rend apart the worlds. He’s also got a really cool coat, and one eye that is completely black, and does blood magic to travel between the worlds.

If this seems like a cursory examination of the setting and set-up, it’s because that’s about all I can muster. Basically, these books were fine — the writing was fine, the setting had its moments, the magic was cool, I guess, but throughout, I struggled to give a shit. This may be a personal antipathy towards London (I am very cranky about major cities), or it may be because these books slightly predate the various Tor imprints’ queerer turn, or maybe because the language of magic never quite made sense to me as its used in the books, but neither Darker Shade nor Gathering of Shadows really clicked for me. There was a lot of flourish, and a lot of generally Cool Stuff (including the book packaging, which is really quite nice), but I just never managed to care.

And it’s not like I’m allergic to fun, since this is about when I finished the fourth installment of Martha Wells’ Muderbot Diaries, Exit Strategy. I’d been hearing about Murderbot for some time, and I now regret that it took me so long to get around to the series — though, in fairness, they’re all novellas, and it was easy to get almost all the way caught up on it. The books follow our dear friend, Murderbot, a SecUnit with a cracked governor module who, as of the first book, has been continuing to do its job and trying not to get caught (and keep watching The Rise and Fall of Sanctuary Moon, its favorite serial drama). But it doesn’t take long for its behavior to begin slipping, and pretty soon, the humans it has been ordered to protect are on to it — if something else doesn’t kill them first.

I could have put the covers, but this little meme, featuring an edit of one of the covers and a play on the William Carlos Williams poem and used in a brief Tumblr interview with the author, really just sums up the vibe.

That’s really just the first book, and the subsequent installments follow pretty closely from the plot established in it. Wells does an excellent job of balancing Murderbot’s delightfully snide voice against the movements of the plot, and the action sequences — which are many — are concise and easy to follow, two qualities that are somehow often lacking in literary fight scenes. And I’ll admit, as someone currently working in security (albeit the most Wes-Anderson-esque version of security), Murderbot’s annoyance at, like, doing stuff was very relatable. I also loved Murderbot’s approach to gender and sexuality: adamantly asexual, Murderbot also is less gender-fucked than gender-fuck-you. I’m very excited to see where the series goes.

The cover of Crier’s War, from Amazon.

Which gets me, finally, to the end of this rather lengthy round-up, culminating in Crier’s War and Iron Heart by Nina Varela. I was pointed to the duology by my younger sister, and I would have finished Crier’s War a lot earlier had my loan of the audiobook not been forcibly returned, leaving me to wait to get it back with one single chapter left. The books follow Crier, an Automa (basically a robot powered by alchemy and magic) noble with high ideals, and Ayla, a pro-human revolutionary, as their paths collide. The two girls, drawn together through the unwitting machinations of the charismatic leader of the Automa Anti-Reliance Movement, are both seeking some kind of justice, some kind of reckoning, but they also, ultimately, find love with one another.

The cover of Iron Heart, also from Amazon; I put in both of them because I think they’re pretty.

Varela set herself a high bar here: the worldbuilding is intricate, to put it nicely, and the setting, which features both robots that are almost indistinguishable from humans, and what seemed to me to be almost eighteenth-century European design aesthetics with respect to clothing, furnishings, and most of the rest of their technology, was kind of a to unpack. But I never felt adrift in it, and the novel is fueled by the complexity and growth of the central characters as they are embroiled in political machinations and social evils that run deeper than either had imagined. Both Ayla and Crier were extremely compelling and, unusually for the kind of YA fantasy that I like, never felt as if they were written older than they are. Both have had terrible experiences at the hands of a fundamentally fucked-up society, but both also feel like girls in their late teens. It’s a hard balance to maintain, but Varela does it beautifully. I am excited to follow Varela’s career as it unfolds, for sure.

※

That’s it! That’s all! I’ve read more stuff than I can comfortably fit in a book round-up, but I refuse to learn from this experience and will probably continue to consume literary content at a horrifying pace! Cameron and I are both on Twitter now, and can be found here and here respectively! Have a nice day!