Gunpowder Mithridatism

An image of a fireworks display, uploaded by wikimedia commons user ParentingPatch and used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

So, Sunday was the Fourth of July – it was that everywhere, but it means something different in America – and I’m still unpacking what the holiday actually means. Over the past year, we have seen the government grow somehow even more sclerotic and incapable of doing anything, to the point where there was an attempted fascist takeover in January. We have seen our northern neighbor begin to reckon with what it did to the indigenous people of this continent (and, of course, we have ignored what we, ourselves, have done.)

What, in the twenty-first century, is the meaning of the Fourth of July?

According to wikipedia, the first celebration was in 1777, before the revolutionary war had yet ended. It wasn’t made an official holiday until 1870, and wasn’t a paid holiday for federal employees until 1938. Fireworks have been part of it since the beginning, and it’s mostly the fireworks that I’m interested in.

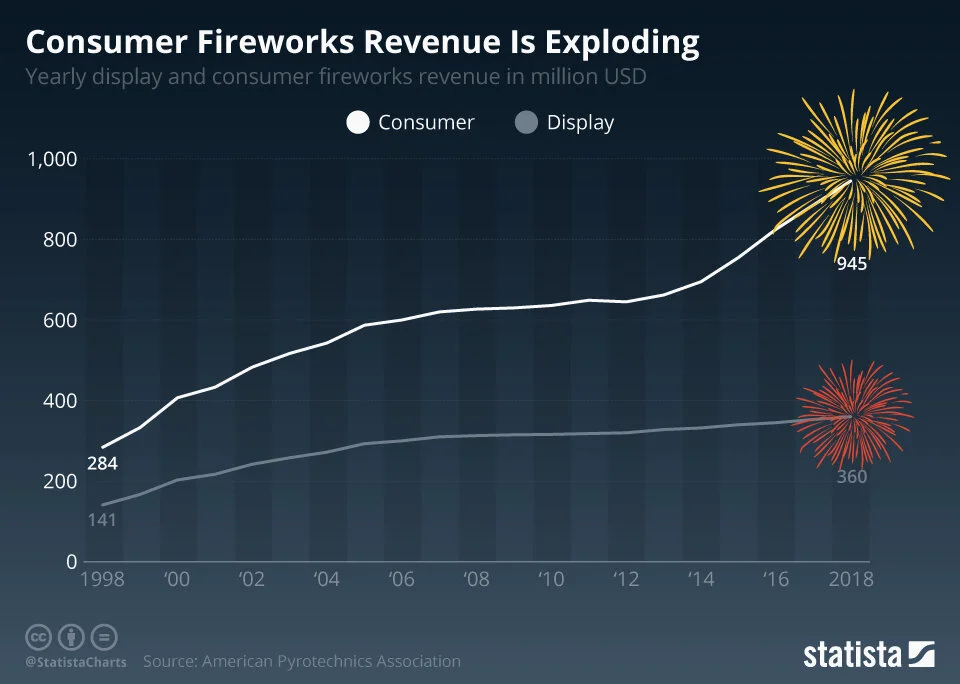

I could only find a graph for consumer fireworks sales by year, going from 1998 to 2018 – a period during which consumer fireworks sales ballooned from $284 million to $945 million (a 332.7% increase), while professional grade fireworks went from $141 million to $360 million (a modest 255.3% increase.) Notably, this amount increased from 1998 to 2005 and then plateaued until about 2014, where it began to increase again.

Last night (and I write this on Monday – I have a new work schedule to navigate, and I’m trying to stay ahead of things,) a friend of ours from California pointed out that, in his experience (which is not universal, but is a data point,) fireworks aren’t really a thing. Which suggests that fireworks consumption isn’t evenly distributed. If you look at this 2018 map of per capita fireworks spending, assembled by CNBC, you see that most of the $945 million USD was spent in Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Mississippi, and South Carolina, followed by Wyoming, North Dakota, Nevada, Indiana, and Ohio. This is, of course, per capita – there are almost five times as many people in Texas ad there are in Missouri, but they spend fifty cents per capita instead of $3.50 (meaning that their total spending is roughly on par with that of Indiana, if my math is correct.)

And, of course, there’s the issue of illegal fireworks, represented by this tasteless ethnic caricature from the Simpsons.

So this brings us to an interesting problem: why are fireworks so much more prevalent in the three center-most states in the United States? Were they settled exclusively by pyromaniacs? It can’t simply be the vast emptiness – New Mexico, Arizona, and Oklahoma are all likewise quite empty-seeming, and their sales are approximately zero dollars per capita, and of these only Arizona has a total ban on fireworks that I can find. Statewide excise taxes are imposed in Georgia, Indiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia – but residents of Indiana are still near the top of the list for fireworks consumption while it’s at $0 per capita in Georgia.

It seems that there is something almost peculiarly midwestern about the jouissance of fireworks (for more on jouissance, see my piece about online discourse.) Something that is shared by one Deep Southern (Mississippi) and one Southern-Atlantic (South Carolina) state.

I do not have enough information to make any guesses about states apart from Missouri. There are, however, things that I suspect.

My suspicion is that, over the past twenty years, there has been a shift toward social conservatism in what we could call the “Deep Midwest” (Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska, as well as immediately adjoining areas, of neighboring states) that shows a particularly American character. American conservatism, for all of its talk of community and family, is first and foremost an individualist ideology. Consideration for others tends, in my experience, to be out of a desire to avoid personal trouble, rather than actual consideration for the needs of others, for example.

An advice duck meme about fireworks — note the bottom text.

The best sign of this, I think, is in the fact that many veterans actively dislike the use of fireworks. It’s a common PTSD trigger, and the same people who for decades have been discussing the importance of supporting “the troops” would scoff at the idea of going without fireworks on the Fourth of July. Of course, this might boil down to the fact that – while they love and support the troops, – many of these people actively dislike veterans. Freedom might not be free, but god forbid you actually give something like honor or respect to the people that supposedly secured it for you. A big part of this is most likely the fact that a veteran is a person, while “the troops” are a convenient fiction that works as a thought-stopping cliché.

And remember, in the Deep Midwest, it’s not about considering others, it’s about avoiding trouble. And when enough people are being inconsiderate, it begins to look an awful lot like being considerate. Which brings us to my second main point about this holiday.

The Fourth of July, as a holiday, is a ritual to give a hit of communal jouissance that we deny ourselves – or are expected to deny ourselves – at other times. Consider, we have no holidays that allow us to interact with strangers without the fear of danger: it’s basically just the Fourth of July and Halloween (a fireworks holiday in British Columbia and Ireland, notably,) for Americans, and for residents of the USA, Halloween is basically always going to have a certain stank of stranger danger. Fourth of July allows you to feel yourself woven into a community – and there is danger, but it is a danger that you are expected to, as a group, conquer and enjoy.

Untitled by Barbara Kruger.

I am reminded of Barbara Kruger’s piece in her series of untitled works that includes the text “you construct intricate rituals to allow yourself to touch the skin of other men” – an image and statement that have attained an iconic meme status on Tumblr but haven’t seem to have escaped the gravity well of that particular platform. It is a statement about toxic masculinity – a subject I’ve written on several times – and it’s very true. Contact sports, especially combat sports, the rituals around alcohol consumption, and other such stereotypical masculine activities are designed to “safely” allow physical touch between cisgender straight men (as if the skin of another is in any way inherently dangerous.) The Fourth of July is a similar ritual – it is a ritual to allow people to exit the oedipalized space of their individual home and enjoy watching an explosion in relative safety. It gives a hit of community, and allows the destructive urge to be boiled off.

In short, it’s sort of a tame riot, and avoiding participation is seen as strange and unusual.

A homemade assault rifle casing for roman candles. Why does this exist?

Consider: it’s a temporary community, briefly erected to simulate the effects of a black powder-age battle. Or, it was. I noticed on Sunday a fair amount of roman candles put in casings that made them look like the sorts of weapons the armed forces are deployed with, complete with stocks and cardboard magazines. Now you, too, can be a troop. At the end of it, we clean up, and go back into our houses, and act like what just happened was completely normal.

I feel like, as the past twenty years have rolled on, the destructive urges meant to be burned up by this have built up – more and more has been left to mature and fester, and it’s not been completely used up in the course of the holiday (consider how many people have begun to add fireworks to their New Year’s celebrations, for example.) As people want to see more and more destruction, they buy up more and more fireworks.

This might possibly be due to the fact that we’re at war but none of us feel like we have the experience of being at war. And because of the tendency of contemporary people to cast themselves as the protagonist, no one wants to sacrifice or give anything up as was done in World War II (our last successful moment of full mobilization.) No, they want to feel as if they’re present in front line conditions.

So, we have changed the holiday to more accurately reflect what we feel is appropriate. It has evolved through stages over the centuries, becoming something different for each generation to use and understand. It began as a simply memorial for something that has happened. It then evolved into a collective statement of purpose. As time went on, the statement became less important, worn away through reiteration, and it evolved into the fact that it was being said together.

I think it is important to note that this is all something of a thought-stopping cliché. Even citizens who question – or outright despise – the American project for one reason or another seem to put this on hold for twenty-four hours and take part in the performance of collective patriotism and, in certain parts of the country, take the time to blow up a small portion of it, if only for the crack heard in the ears or the shudder that passes through the diaphragm.

Looking at all of this, I have no prescription or final thoughts. I think that, when you get down to it, it’s a fairly stupid holiday and when I have been roped into celebrating it, it’s taken on a perfunctory air. Sort of like being convinced to go to church on Christmas or Easter, but with slightly more chance of losing a finger.

※

Here’s what you need to know about Georges Bataille. He founded a secret society called Acéphale because he was fascinated by human sacrifice. Everyone who joined agreed to be the sacrifice in such a ceremony, but none of them agreed to be the executioner. They tried to hire one, but then World War II happened.

After completing this and reading back over it, I’m also reminded of another idea from theory that could also have some currency here: the “accursed share” from Georges Bataille (a writer I need to read, but whose ideas I have encountered secondhand). This is the idea that a portion of what every society produces is expended in an act that is neither productive (making more material goods) or reproductive (feeding the growth and continuation of a society.) In Ancient Egypt, this was the construction of the Pyramids and other elaborate tomb-complexes. In societies that practice sacrifice – human or otherwise – it was the act of sacrifice. In modern America, it is sending billionaires to space or whatever it is that Softbank does. Probably both.

We spend hard earned wages to buy explosives to set off in such a fashion that we get a momentary enjoyment from the detonation, when we could save that money and buy nourishing food or pay for housing or fuel. But then we would lose out on jouissance or social capital, because we did not engage in the conspicuous destruction that the holiday demands.

Imagine if, instead, we had a holiday where every person was encouraged to publicly burn a fifty dollar bill while loudly proclaiming that they loved their country, and those who didn’t – or who burned a smaller denomination bill – were considered suspect. This is, fundamentally, what this holiday is: a means of disposing of excess money in a lavish, and ultimately temporary, symbol of fealty.

In all honesty, I’d personally rather do without.