Edgar's Book Round-Up, December 2021

So 2021 finally ended. I read some more books. Here’s some stuff about them — once over lightly, but it’s not nothing. Links go to our Bookshop, as per.

※

The cover, which, as colorful blob covers go, is pretty nice, I think.

The Death of Vivek Oji, Akwaeke’s Emezi’s most recent adult novel (though not for long — their next adult novel is due out later this year, and that’s leaving aside the forthcoming prequel to Pet and a poetry collection) leads off this round-up. An impulse buy from a beloved bookstore in my area — after, of course, following some of the book’s predictably-stellar critical response, of which this NPR review is representative — it waited on my shelves for a little while before I finally picked it up. When I did, I finished it in about 72 hours (24 of which were spent at work, which might tell the reader something about the novel’s strength). The novel, as the title suggests, finds its center around the titular death: Vivek Oji’s body is returned to his parents’ house, wrapped in cloth and showing signs of a head injury. Narrated, for the most part, by Vivek’s mother and his childhood friend, Emezi disrupts what might otherwise have been a fairly conventional novel, exploring the effects of grief in a community that is simultaneously tightly-knit and riven by disputes by inserting Vivek’s own post-mortem narration of what happened. And the community in which Vivek grew up, the Nigerwives, is itself interesting: a community of women from all over the world who have married Nigerian men. All this is cool, of course, but what truly shines is Emezi’s writing, which moves the novel with propulsive, organic force: like a time-lapse of a flower blossoming, dying, and growing again, Emezi once again shows their incredible skill by making it look easy.

I next finished Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places by Colin Dickey, whose other book Cameron discussed here. Ghostland, which I read as an audiobook, more or less does what it says on the tin, examining not so much whether places are haunted as why we want them to be. Broken down by types of places — institutions, houses, hotels, and even cities — the answers are often very much what one might expect: in America, we want places to be haunted because facing the enormity of the evils carried out throughout our history is even more unthinkable than the concept of the unquiet dead. Dickey marshals a lot of good information and journalistic detail behind his easy style, and though he makes his point repeatedly throughout the book, it never becomes tiresome, and I’m certainly looking forward to reading his other work.

The cover, which is, in fairness, part of why I read the book to begin with.

The only ebook in this roundup is Freya Marske’s A Marvellous Light, the first of a projected trilogy. It follows Robin, an energetic young up-and-comer who finds himself shuffled off to a bureaucratic post that seems to be a dead end. But it is soon revealed that Robin has been placed in charge of a semi-secret department which governs the use of magic in Britain — and not only has his predecessor disappeared under mysterious circumstances, but he has to learn to put up with high-strung, cold Edwin, the liaison from the world of magic, tasked with Robin’s “unbusheling” (the revelation of magic and how it works). This was, admittedly, very much within my wheelhouse, given my love for C. L. Polk’s Kingston Cycle — though perhaps that worked against it. Marske was very concerned with the progression of Robin and Edwin’s relationship, and perhaps a little less with the impact of magic in the world, and certainly less interested in political ramifications that Polk was, which for my money, was a drawback. But it was still quite enjoyable, and I appreciated Marske’s attention to aesthetic: I could very clearly picture her settings, which was oddly refreshing.

Next up was what I assume was the final book in A. J. Hackwith’s Hell’s Library series, The God of Lost Words, which finds the heroes — and, of course, Hero — of the previous books attempting, this time, to save not only the Unwritten Wing, but every library in the vast, dimension-spanning network of libraries of things lost, undone, unspoken, and unspeakable. To be quite honest, the best thing I can say of the series is that it’s good fun: the cosmology is nonsensical; the characters vivid but often lacking depth; the prose — especially in this volume — good enough to be getting on with, but often given to digressions on Story, Humanity, and other title-cap Concepts that I could have done without, or at least with less of. This is not to say that this book, like its predecessors (which I discussed here), is anything less than enjoyable, only that it’s better enjoyed than thought about deeply. That said, I’ll be keeping an eye out for more from Hackwith, because sometimes it’s nice to have a little romp.

Another audiobook followed that one: Jess Kidd’s Things in Jars. I think I heard about Kidd’s work via one of my favorite Bookstagram accounts (run by a personal friend), and had, as I often do, backburnered it for when I was in the mood. And Kidd certainly builds a mood: Bridie Devine, an under-the-table detective for the burgeoning Scotland Yard, is asked to investigate the kidnapping of an aristocrat’s secret daughter — which is already a lot, but she’s accompanied in her task by the ghost of a heavily-tattooed boxer, and also the missing child seems to be preternaturally gifted at killing people. Kidd revels in the grotesquerie of her period and her setting: London under Victoria’s reign wasn’t exactly a safe or hygienic place to be, and Kidd lingers on the smells of the city, the grim brutality of it echoing the worst excesses of Gormenghast without any of the fun or the whimsy. Frankly, I found it delightful, and I’m excited to read more of Kidd’s work.

The face of a man who may or may not have invented Wordle, via Wikipedia.

The next print book I finished was a birthday gift from my perhaps-too-encouraging parents: the revised fourth edition of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. While I am not educated enough on things to get too much mileage out of the facing-page German, the translation offered here was clear and energetic. It’s definitely a book I’ll need to read again — there are too many lengthy descriptions of language “games” that seem less like games than pure torment — but I knew I would enjoy it when, on reaching the end of Wittgenstein’s preface, arrived at the following lines:

I should not like my writing to spare other people the trouble of thinking. But if possible, to stimulate someone to thoughts of his own.

I should have liked to produce a good book. It has not turned out that way, but the time is past in which I could improve it.

Same, Ludwig — same.

The last audiobook I read in 2021 was a full-cast recording of Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, the ten year anniversary edition. And it’s hard to know what to say about it: I read American Gods for the first time when I was maybe 14 or 15, I think? I then proceeded to read it three or four more times, at roughly six month intervals, after that, and returned to it a time or two subsequently, but — key, here — haven’t gone back to it in at least ten years. Returning to it now, in my 30s and twenty years out from the novel’s publication, it feels simultaneously fresh — Gaiman’s style, while admittedly almost insufferable in the introduction to this edition, still feels as gothy-bright and chthonically-tuned-in as ever in the novel itself — and like a time capsule or a time traveller. Its influence is hard to calculate or overstate; its lacunae feel obvious now but weren’t, I think, anything like as clear at the time; its impact on me personally was so profound that, rereading it again, I was stricken repeatedly by how much of that book I stole wholesale to build a personality out of. I still like it, which is a relief, but I think if I had somehow only read it for the first time now, I might not be as blown away by it as I was as a kid in the early ‘aughts. But now here I am, for better or worse!

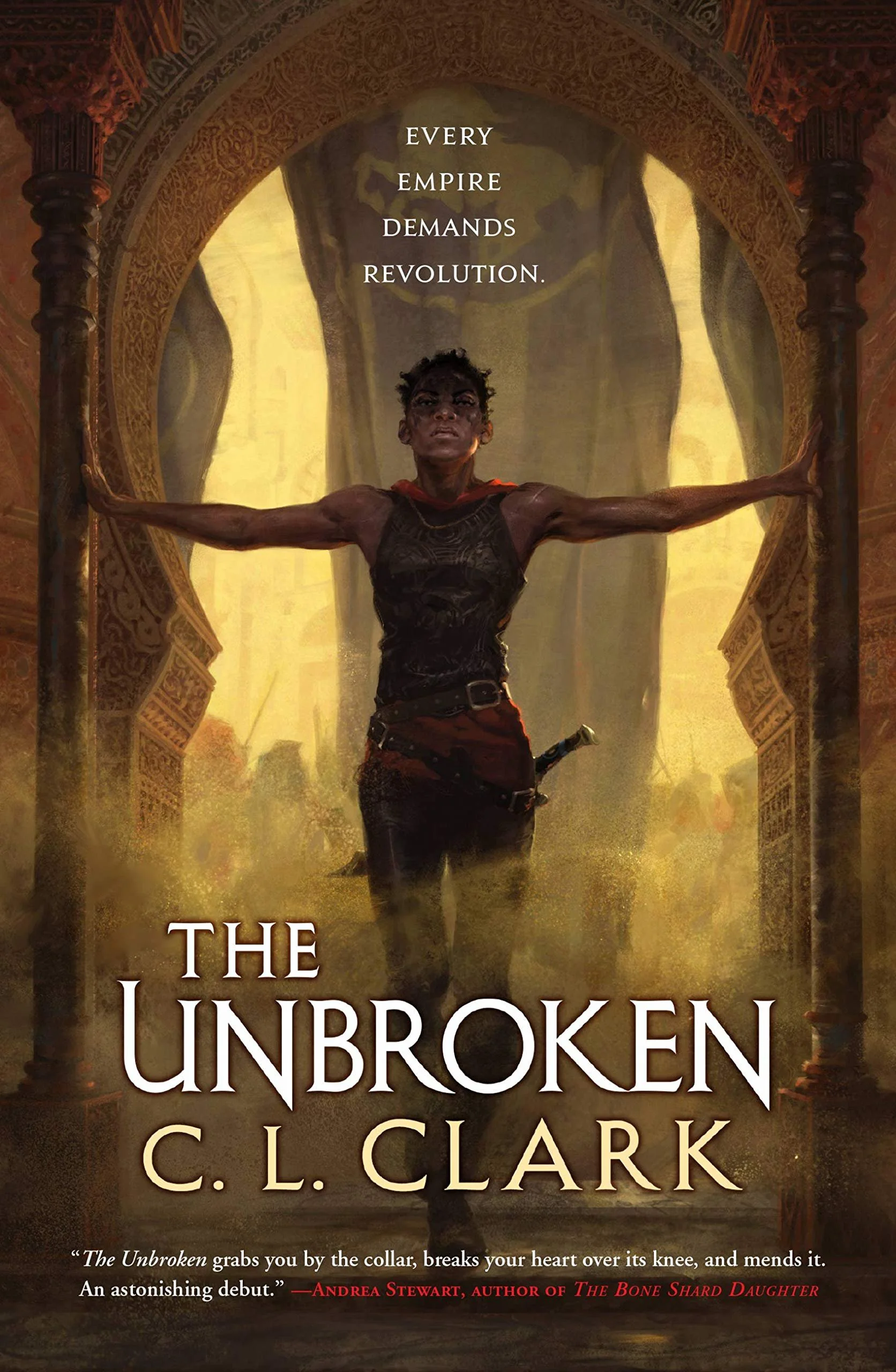

The cover, featuring Touraine’s arms; I recall Clark detailing what Touraine’s arm routine might be on Twitter, but cannot find it now.

I closed out the year with C. L. Clark’s The Unbroken, which I knew I would like from the opening image of Touraine, one of our two narrators, leaning over the bow of a ship, wrapped in a black military coat. Touraine is one of a cohort of colonial forces, arriving as part of the military retinue of Princess Luca to reassert her imperial power over Qazal — from which Touraine herself was kidnapped as a child. But just as Touraine is scrambling to protect those close to her, Luca is scrambling to prove her own ability to rule to her uncle, who has claimed regency of the throne of Balladaire, which she believes should be hers — as well as the secrets of Qazali magic. Needless to say, none of this goes well, and the novel roars along with the terrific energy of political instability, magical contrivance, and, of course, queer women with swords, which I, at least, always love. It was a phenomenal novel — simultaneously exciting, richly-constructed, and thoughtful in its approach. I also appreciated Clark’s awareness of her characters’ embodiment: Touraine, a hardened soldier, is very aware of her body and its limits and how to use them to her advantage; Luca suffered an injury as a child that left her with a bad leg, but nonetheless trained to learn to duel. Given Clark’s own background as a personal trainer, I wasn’t surprised by this, but it definitely helped to keep the story grounded. Also, having the rapacious imperial power be French-coded was a refreshing (and equally-accurate) change from the norm.

※

That’s all. I’m clipping along at a solid pace, still, so these will probably remain monthly columns. If you’d like an intermittent void-scream from me, I’m very occasionally on Twitter; for more frequent contributions, I suggest following Cameron.