Edgar's Book Round-Up, January 2022

It’s a new year! We’re one month in and things are already weird! I read 12 books this month and you can read about them here, and the number is that high because I read four of them in the first week and a half of the year while Cameron and I were in isolation due to COVID! In the throes of my sickness (which was honestly not bad, because I am vaccinated and boosted), I found myself unable to focus on much besides reading, and unfortunately, everyone else has to hear about it. As usual, book title links go to Bookshop.

※

I led off the year with The Twisted Ones by T. Kingfisher. Much like The Hollow Places, which I loved unreservedly, it takes as its inspiration a classic work of now-public domain weird fiction, in this case Arthur Machen’s “The White People.” Needless to say, that title wouldn’t hold, and as in The Hollow Places, Kingfisher ably moves the story into the twenty-first century. A woman named Mouse is called upon to clear out her unpleasant grandmother’s horrible hoarder house after the grandmother’s demise, and she rises to the challenge. After all, who else is going to do it? But while cleaning things out, Mouse stumbles on her grandfather’s notes about an occult ritual, a strange new world, and the “deer” that run by the house in the night. The novel clips along at a brisk pace, but Kingfisher’s genius for creating an adult protagonist who clearly lives in a world we recognize — hauling her battered laptop down to the local coffee shop in between collecting and discarding the trash of the house to work on her freelance jobs, stymied by poor cellular service in rural Appalachia, and that sort of thing — is very much on display here. I personally found more to connect with in The Hollow Places, but between these two novels, I’m very excited to read more of Kingfisher’s work.

One of Machi Abe, the author’s wife’s, illustrations for The Woman in the Dunes.

I followed that with Kobo Abe’s The Woman in the Dunes, as translated by E. Dale Saunders. Being a relatively dedicated watcher of anime, I felt a bit remiss in not knowing more about Japanese literature beyond the works of Haruki and Ryu Murakami, and we already had a copy of this one, which follows an amateur entomologist as he becomes trapped in a nameless town that is being overtaken by dunes without a sea, where he stays with the titular woman. Abe was, I have since learned, very much influenced by Dostoevsky and Kafka, and while those influences are on clear display here, Abe’s approach to, essentially, existentialism is balanced by a sense of incredible embodiment: the protagonist (whose name is, for some reason, stressed in back copy of the edition I have, but which the reader does not learn until halfway through the novel) suffers from skin irritation due to the ever-present sand, and is horribly sickened by the conditions in which he lives. It’s easy to project analogies onto the story — what sprang to mind for me was the social pressure to conform to a given life-path, doing a stupid job day in and day out to satisfy a partner with whom one has been placed more or less at random — but it’s a weird one, and defies a neat filing in that way. It’s worth noting, too, that this translation really leans into the existentialism of the novel: almost self-consciously, the translator has espoused the literary register of mid-twentieth century translations of existentialist texts, to such an extent that, given a random passage, I don’t know if I would have identified the novel as non-European in origin. But that is, I suspect, more the fault of the translator than the author. I’m definitely looking forward to digging into Abe’s oeuvre, as well as learning more about twentieth-century Japanese literature.

Next up was Emily Bronte’s inarguable classic, Wuthering Heights. Having read Jane Eyre and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, I am excited to be able to claim conversance with all three Bronte sisters — but that’s a personal problem. Wuthering Heights finds its center (as I’m sure we’re all aware) in the toxic, overwrought romance between Heathcliff, an orphan adopted by the Earnshaw family, and Catherine, the Earnshaw daughter, as they fuck each other up forever. But I was thrilled to discover that, while the Catherine/Heathcliff relationship forms the burning core of the novel, its effects spiral into injury to everyone who comes near them. Narrated by Ellen Dean, who was raised alongside Catherine and Heathcliff but is resolutely of the servant class, and told to a Mr. Lockwood, who has taken up residence at the Grange, a neighboring house once owned by the Earnshaws as well, the nigh-apocalyptic intensity of Heathcliff and Catherine’s love/infatuation/mutually assured destruction wounds everyone who enters into its orbit. Bronte’s insight into cycles of trauma, and the stark contrast she establishes between the wild moors and the nigh-incestuous, claustrophobic family that treads them, are as striking today as they were when the novel first appeared.

The cover, from Repeater’s Twitter.

Continuing in the gothic vein, while still romantically quarantined, I picked up Darkly: Black History and America’s Gothic Soul by Leila Taylor, which I picked up when Cameron and I ordered a bunch of stuff from Repeater Books during one of their sales. Combining memoir, literary criticism, and sociology, Taylor deftly weaves a dual analysis of goth and the gothic as a subculture, a genre, and an inescapable historical fact of America’s history. Along the way, she treats us to reminiscences of her youth in Detroit, early encounters with goth and being goth, and a truly beautiful reflection on her experiences with the song “Strange Fruit.” I can’t speak highly enough of Darkly, and I hope to see more from Taylor in the future.

Still in isolation but preparing to return to work, I next finished off C. J. Tudor’s The Burning Girls. From a promising premise: Jack Brooks, a single mother and CoE priest, is shuffled off to a remote village where some truly grim protestant martyrdom happened in the 1500s, but Jack herself is pursued by dark shadows, and she and her daughter are immediately plunged into an atmosphere of threat and secrecy as they seek to uncover the truths that the village hides. Unfortunately, the premise is more or less the best thing about it. The writing was fine, for the most part, but at a certain point Tudor began to attempt twists she hadn’t earned, and the whole things ends in with a weird, paranoid white-feminist fever dream. To put it mildly, it was really not great, and I probably won’t be returning to Tudor in future — though I say “probably” because I do like to read bad things sometimes.

The truly lovely cover.

Fortunately, I next picked up The Four Profound Weaves by R.B. Lemberg, which was up for a Nebula and is also — full disclosure — written by one of my younger sisters’ beloved professor. Set in Lemberg’s Birdverse, and following on this story in particular, The Four Profound Weaves centers on the nameless man (who does, in fairness, settle on being called nen-sasair for most of the story) and Uiziya e Lali as they attempt to prevent the despotic ruler of Iyar, known only as the Collector, from collecting the titular woven artifacts and using them to gain god-like powers. Straightforward enough, but I knew Lemberg first as a poet and a keen editor of poetry, and coming to something like The Four Profound Weaves for the plot would be a mistake. The Birdverse is a profoundly queer and unapologetically Jewish setting, and Lemberg is very much working in the register of myth or fairy tale — think of the stories that make up The Mabinogion and you’ll be in the wheelhouse. But quite beyond a real mastery of that register (which is really not as easy as many would like for it to be) Lemberg gives us such deeply compelling characters. Centering a story on relatively aged trans people is a bold move — and in lesser hands, could have been the only move, leaving us with little. But both Uiziya e Lali and nen-sasair come to wear their lives with pride and determination, in part by learning to live with their various griefs, but also to celebrate their various joys — though for perhaps obvious reasons, nen-sasair spoke most deeply to me, especially in his conflicted relationship with the womanhood he chose to cast off. After having encountered their work intermittently for so long, it was a real pleasure to experience Lemberg’s longer-form prose, and I hope to seek out more soon.

Now fully returned to work, I next made my way through the latest in Seanan McGuire’s Wayward Children series, Where the Drowned Girls Go. I’ve made most of my thoughts on the series — very good! I love the many-novella structure! — pretty clear elsewhere, and this one did not disappoint. It does, however, advance the overarching plot of the series, and discussing it absent the others would be less than useful. Moving on, then!

The cover, which is admittedly pretty cool.

Unfortunately, I moved on then to Appleseed by Matt Bell. Blurbed by luminaries like Kelly Link and compared to Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy, I’ll admit I got my hopes up quite a bit: I first encountered Bell’s writing right around the release of his first short story collection, and have been relatively avidly following his career ever since. But I took my time coming to this one, mostly because I recalled being disappointed in his previous novel, Scrapper. Still, I approached Appleseed with interest: I liked the conceit of having several narrators across wildly disparate times, and if nothing else, Bell’s style is reliably fucking fantastic. This paragraph began with the word “unfortunately,” though, because as much as I wanted to like Appleseed, a few things rubbed me the wrong way, and rubbed harder for how much I loved so much of the rest of it. Bell’s nature writing is an unexpected treat, for example, and many of his preoccupations — the last person in an outpost at the end of the world, for example — are fully on display. But character has never really been Bell’s strong suit, and that’s very clear in this novel, where character is really key; somehow, he still managed to be kind of fatphobic for no reason; it strikes me as really weird to mention “genocides” in America, but also have a viewpoint character wandering the land that would become Ohio in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and not once mention Native Americans. Fundamentally, I think, what made Appleseed so frustrating to me was that it was an environmental apocalypse fuelled by devouring capitalism, and there are many ways to render that terrifying (as if like, reading the news weren’t enough) — but Bell wrote a wake-up-call novel specifically for straight white cisgender American men. Which was kind of a weird choice.

Anyway, the next one I read was Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle by Emily and Amelia Nagoski. Since I read it very lightly in one day, I will be brief and say that the secret is to allow yourself an acute release and then get on with it — though I do want to stress that the Nagoski sisters’ writing was fun and easy to read, squarely aimed at more-or-less progressive Millenial women (“Take time in your day for patriarchy smashin’” is one recommendation that they make). Not much new information, then, but well-presented and, perhaps obviously, pretty easy reading.

This is probably about where I started on Tzvetan Todorov’s The Fantastic, to be discussed later; it took me a while to get through, so I’ve got two audiobooks here back to back.

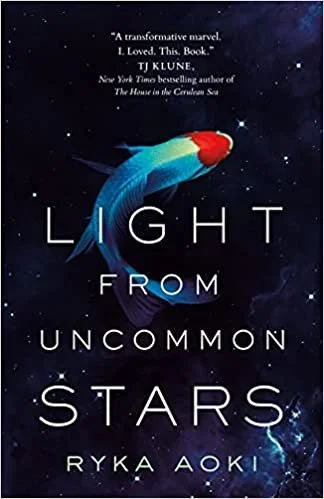

The cover which, while nice, doesn’t really do the novel true justice.

The first of those was Ryka Aoki’s Light from Uncommon Stars. Aoki’s debut novel, it follows — just come with me on this sentence — Katrina Nguyen, a young trans girl running away from an abusive home, as she is taken in by Shizuka Satomi, a violin teacher known as “the queen of Hell,” whose pupils have all been great violinists and who owes one more soul to the demon with whom she made her deal, but Satomi finds herself falling in love with Lan Tran, who runs Starr Donuts with her four children and her aunt as cover for their escape from an intergalactic war that would have killed all of them if they had not fled to earth. None of the plot items mentioned in that sentence is in any way a spoiler; this is all laid out within pages (or, you know, the first hour or so) of the book’s beginning. I’ll admit, I wasn’t sure if such an absolutely kitchen-sink premise could work — but Aoki does it. Not only does she do it, but she does it extremely well: as goofy as the novel could have been, the characters were so tenderly rendered, their relationships so deeply felt, that it absolutely worked. (And was sometimes goofy, but in a good way.) I’m really looking forward to reading more of Aoki’s work in future, and checking out her poetry.

The last audiobook I read in January was a very different story — The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward — but it also has a lot going on in its very premise. Narrated in turn by Ted, a weird loner and put-upon single father, his angry, alienated daughter, Lauren, a frighteningly driven woman named Dee, who is searching for her long-missing sister and thinks Ted killed her, and, of course, Ted’s cat, Olivia, who is a devout Christian and also a lesbian. And Ward, too, manages to pull off a pretty fucking zany premise with relative panache: the characters are drawn with intensity, each as obviously unreliable a narrator as one could want; the pacing is solid, leaving room for weird moments without slacking; Ward has a great eye for the unsettling detail, the horrible things that make me murmur, “hey, now,” out loud while reading. But the novel hinges on a very specific twist, which, though well-executed (honestly, leagues better than many other iterations) was still such a common one, and one that’s so often misused, that it landed more like a half-hearted punchline than a real reveal. I’m not going to spoil it here, but others have, so there’s that if you want. It was good, and with the caveat that it’s the kind of psychological horror novel that really just makes you feel sad, I liked it — but I’m curious to see what Ward can do when she’s not leaning on overplayed “twists.”

The very matter-of-fact French cover which I strongly prefer to the rather uninspired English language ones.

We close out this round-up with a book that hasn’t so much haunted me as appeared at key moments, in a passing citation, but which I never had the presence of mind to seek out until now (or, more specifically, because it was cited in Darkly, discussed above): The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre by Tzvetan Todorov, which I read in Richard Howard’s English translation. It’s hard to overstate, but almost equally hard to clearly state, the influence of this book on discussions of genre fiction broadly, because Todorov doesn’t just outline “the fantastic,” he outlines how genres are built in the first place. I read a library copy, and will almost certainly need to re-read it, but I was mildly disappointed at how much of the book is about genre in general, relative to how much is about the titular genre specifically. Then again, I ran into something similar with Marc Auge’s Non-Places; in any case, what stuck with me the most from this one was the observation that the detective story is the modern (or, you know, mid-twentieth century) iteration of the ghost story.

※

That’s it. That’s all I’ve got for January. As usual, you can find me and Cameron on Twitter.