Edgar's Book Round-Up, September 2022

The cover of The Pariah, with art by Jaime Jones.

I led off September with the audiobook version of Anthony Ryan’s The Pariah, a novel I read entirely on the strength of its cover. And, going strictly by that metric, it didn’t disappoint: as the cover art promises, it gives us the story of Alwyn, a young man of low station, as he stabs, steals, and, swearing it’s borne from self-interest, saves lives on his way to the top. He is every bit as greasy and thinks-he’s-Deadpool as the cover suggests, so that was nice. A more pleasant surprise was the dense layer of religiously-oriented worldbuilding: Alwyn’s world is in the throes of a once-in-a-generation religious conflict, the details of which emerge slowly, in tantalizing driplets in between Alwyn attempting to be clever and/or badass (and usually failing). It was fine! It was fun! I’m going to read the follow-up because sometimes all you need is something that’s good enough and has some bitchin’ swords.

So we began with pulp, and we followed it with disappointment, which is a long way of saying I finally slogged my way through Alex Pheby’s Mordew. The first book in a projected… more than one, the novel follows Nathan as he tries to survive in a city characterized mostly by being muddy, foul-smelling, and utterly unconcerned with its residents’ well-being. There was a bunch of other stuff, too, but frankly, I found myself increasingly not giving a shit: Pheby wants to be Michael deLarrabeiti or Mervyn Peake, and he’s not; instead, he’s verbose and bad at pacing. Perhaps because it’s the first in a series, none of the reveals seemed to matter, and most were signalled and then discarded until the very end of the book, by which time I was skimming really hard. This was also my second run at it, having attempted the audiobook some time last year, discarding it when I, once again, hit a spot where I just didn’t care about anyone or anything in the story. Part of the problem, I think, was Nathan, who is a distinctly British sort of protagonist, unthinkingly attempting to be decent and eternally ground into moral compromise by his surroundings. I’m sure there’s people out there who liked Mordew, but I was not one of them.

The cover of Space Opera.

Next up, also in audio form, was Space Opera by Catherynne M. Valente (whose Past Is Red I discussed here) which takes as its premise: what if there was Eurovision in space that determined whether newly-discovered species were properly sentient? While there was a plot in there, and it was fine, Valente’s interludes covering past shenanigans and horrors at the intergalactic song contest were far stronger, her rapid-fire invention covering a somewhat mawkish tale of a one-hit wonder getting the band back together to save humanity. Then again, mawkishness is a common trait in actual Eurovision entries, so maybe it worked — but throughout the novel, I couldn’t shake the sense that Valente badly wanted to channel Douglas Adams. For the most part, she succeeds, which is nice. It was, on a fundamental level, a fun romp, and sometimes that’s all you need.

After that, I finished Faithful Place, the third installment in Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad books (the prior entries of which are discussed here and here). Continuing to rotate through the members of the squad, Faithful Place focuses on Frank Mackey, the charming, cavalier undercover guy from prior novels, as he’s drawn back into his dysfunctional family’s orbit by the discovery of his high school sweetheart’s body in a derelict house in their neighborhood. Once again, French’s eye for detail lends depth and weight to the story, which could easily have devolved into something not actually interesting. Frank is a deeply compelling narrator, using flippant charm and a readiness to escalate situations to try to preserve his daughter’s innocence in the face of a family that seems to do nothing but lie to and abuse each other (at least, as Frank recalls it). French also writes with a distinct eye to the class backgrounds and positions of her characters. I did, however, end up starting this one in ebook form and finishing it as an audiobook, because it took me a while for no real reason. Do with that what you will.

The cover of the first US edition of Pale Fire, via Wikipedia.

But now we’re getting into the real-bangers section of this round-up, which kicks off with Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire. The novel offers us the text of John Shade’s 999-line poem, whence the title of the novel, as well as an introduction and commentary by Shade’s ostensible friend, Charles Kinbote. Shade’s poem is a sort of reflection on his life — but Kinbote, it rapidly becomes clear, desperately wants it to be something else, something about the fictional country of Zembla. But honestly, any description elides the fact that this is possibly one of the funniest things I’ve ever read, mostly because it’s an act of both incredible skill and unthinkable madness. To be able to write a poem of the titular piece’s type entirely in character, and then offer a hilariously bad commentary that nonetheless feels as if the person writing it thinks they’re writing a perfectly reasonable commentary requires both elements, and Nabokov makes it look easy. Pale Fire was a true delight.

I next read, in ebook form, A Prayer for the Crown-Shy by Becky Chambers, the second installment in her Monk and Robot series, the first of which I discussed here. In Prayer, Sibling Dex (the monk) and Mosscap (the robot) have reentered human society, as Mosscap seeks the answer to its question for humankind: “What do you need?” And perhaps because there were more characters, and more about the society that gives us small gods and wilderness robots, I enjoyed this one substantially more than the first. When Chambers decides to do plot, she does it extremely well, and the setting details in this book were much more interesting to me than the wildwood of the first book. As a long-time fan of monks and robots (thanks, Ken Scholes specifically), I’m definitely looking forward to further adventures from our protagonists here.

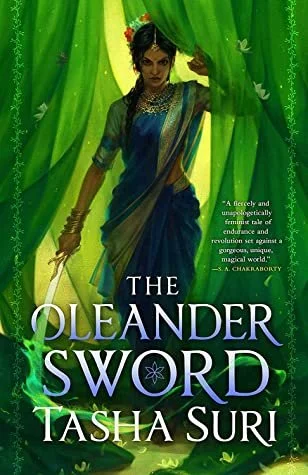

The cover of The Oleander Sword, which I absolutely love.

My next audiobook was Tasha Suri’s The Oleander Sword, the second installment in her Burning Kingdoms trilogy (the first of which I discussed here). Picking up not long after the first novel ended, The Oleander Sword takes up Priya and Malini’s respective political struggles once again: Priya, to gain greater magical power and independence for Ahiranya, her home region; Malini, to wrest the throne from her femicidal zealot brother. But neither of them can gain the power they seek without cost, and both women — and their love for each other — are threatened by the forces that rise against them. As much as I enjoyed The Jasmine Throne, if anything, I felt that The Oleander Sword was stronger still: the battle sequences, especially, were both clear and gripping; the escalation of threat throughout the novel was extremely well-handled and left me wanting more at every turn. I’m very excited for the third installment, which is expected some time next year.

I’ll note briefly that here is where I began reading the Laundry Files novels by Charles Stross in audiobook form, at Cameron’s recommendation. They’re fun! The Atrocity Archives, the first one, fell within the temporal bounds of this round-up. I mention it only in passing, though, because of what I was reading in print for the last couple weeks of the month.

All three books! They’re all really good!

It was Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb books! Which I love! And because Nona the Ninth, the surprise third installment of what is now no longer a projected trilogy, came out this past month, I decided to reread Gideon the Ninth and Harrow the Ninth, but obviously only to refresh my memory a little and not because I’ve been yelling at everyone I know to read them for quite some time now and I’ll take any excuse I can get to hang out in a world I’ve characterized as being like if Zdzisław Beksiński did van art. I’ve discussed Gideon here and Harrow here, and stand by those assessments. It’s difficult to discuss Nona without spoiling either it or one of its predecessors, but I’ll do my best. Nona, like Harrow, takes a radically different tone from its predecessors, following, by turns, the sweet-natured, child-like title character, and two figures in a ruined landscape, talking about the end of the world. The novel also offers us something more like a ground-level view of Muir’s necroverse: Nona and her friends live in a derelict apartment building in a war-torn city, providing a refreshing look at how the other 99.999999% of people live, as opposed to the rarified locales of the prior two books. And Nona’s innocence allows Muir some end-runs around the plot, offering the reader ample opportunities to, for example, hypothetically, scream into a pillow, or whisper, “Oh fuck, oh fuck you, fuck,” in response to them. I will simply close by saying these books are so fucking good that I’m afraid I’m going to have to read Homestuck about it.

※

That’s it for this month. Follow me and Cameron on Twitter if you want.