We Have Always Been Postmodern.

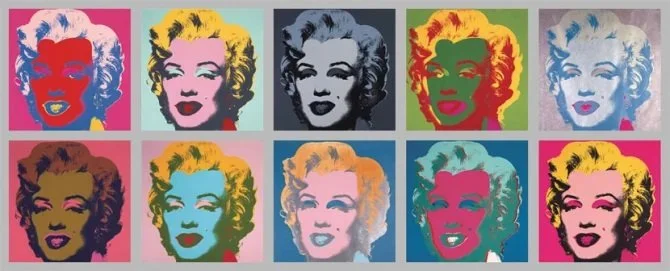

Andy Warhol’s painting of Marilyn Monroe, in a number of variations — the practice of iterating on a theme is key to the concept of simulacra, which is neither original nor copy, but occupies a confused area between the two. The Postmodern Period is characterized by the disappearance of the original and the proliferation of mutant simulacra.

[This piece should be thought of as a companion to my much earlier piece “No One Ever Chose To Be Post-Modern”, though I haven’t taken the time to read that and as I write this it is both very early and I must leave for work soon; I imagine I’ll have to break in the middle of writing this and return to it later.]

I recently read Otaku: Japan's Database Animals by Hiroki Azuma – the University of Minnesota Press was having a sale, and it came at a time when I had the money to grab some things, so I behaved unwisely – and it served as a catalyst for altering my understanding of Postmodernism as a whole. I’m still grappling with the implications of some of the ideas presented, but it all seemed fairly cogent: it’s simply the cascade of changes I’m working through.

Early in the book, Azuma lays out two principle questions that he wants to answer:

The two questions are:

1. In postmodernity, as the distinction between an original and a copy are extinguished, simulacra increase. If this is valid, then how do they increase? In modernity, the cause for the birth of an original was the concept of “the author.” In postmodernity, what is the reason for the birth of the simulacra?

2. In postmodernity grand narratives are dysfunctional; “god” and “society,” too, must be fabricated from junk subculture. If this is correct, how will human beings live in the world? In modernity, god and society secured humanity; the realization of this was borne by religious and educational institutions, but after the loss of the dominance of these institutions, what becomes of the humanity of human beings? (p. 29)

Azuma’s answer to it lies in what he thinks the “meta-narrative” or “grand narrative” has evolved into – he speaks almost solely about the Japanese – and specifically the otaku – conception of it, but I think the idea has broader applicability.

I won’t summarize Azuma’s whole argument, but the basic answer to the first one – which is a necessary precondition to his answer to the second one – is that the “grand narrative” has become a sort of database; a “grand nonnarrative”. There are small narratives that we encounter in the world – media properties, flash fiction we found online, inside jokes with our friends, so on and so forth – exist as neither copies nor original works: they are simulacra built up from a storehouse of common features that Azuma likens to a database. For those familiar with Japanese pop culture, the example that he uses is the production of “Moe” characters, who are (principally female characters) simply assembled from series of tropes that have been successful in the past in capturing audience attention – maid uniforms, large socks, cat ears and tails, emotional coldness, so on and so forth.

What is notable here is that the addition of a new element to the database leads to a cascade of remixes and quotations and parodies and variations whereby the new element leads to an explosion of new mutations of the form as it is juxtaposed, incorporated, parodied, and otherwise used. This means that, more so than having a coherent story, the producers of narratives want to capture attention and do so by rapidly incorporating anything that seems successful (in this way, the logic of markets is imposed on aesthetics: every Dr. Pepper calls for a Mr. Pibb.)

I don’t know about you all, but this immediately put me in mind of TV Tropes – the absolute black hole of the internet – where every element of culture is broken apart and dissected and pinned like a butterfly so that it can be examined, with an attempted collection of all references to that particular trope laid out.

If you float around writing spaces on the internet long enough – and I’m sure that you find these in other spaces, not just those frequented by writers – you will find people dropping the “names” of tropes into conversation, even to the point of some people insisting that the term used on TV Tropes is the “proper” name of the trope.

Moreover, these discussions almost always come about in discussion of the production of narratives, as if a story can be made by stringing the correct tropes along in order. As if there is a formula for the perfect story that could maybe be one day discovered.

This, of course, feels like a mistake. I like TV Tropes just fine, and it’s great as a descriptive tool, if you’re trying to find a particular sort of work. I’ve certainly discovered books and films on there that I later enjoyed. However, people often confuse descriptive with prescriptive: this works to describe, so maybe I can reverse engineer this into the creation of a work? Perhaps I can make these tropes into an erector set?

This is a variation of the Is/Ought problem, which is frankly one of the most frustrating things in the field of philosophy, and something that postmodern philosophy in general suffers from. I’m writing, of course, about the phenomenon where a writer will sit down and describe what is the case with something, and readers, critics, and commentators will then insist that the writer is describing not what actually exists, but what ought to be the case. You can see this with the reception of Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy, as well the reception of the work of Gilles Deleuze. Because they were describing the victory of capital, the establishment thought that these philosophers were cosigning what had happened in May ‘68 instead of having an earnest conversation for how to come up behind the victorious state with a foreign object and make it bleed like a stuck pig.

I contended in my prior piece that this was the issue with postmodernism. The philosophical descriptions of postmodernism were not “ought” statements but “is” statements. I’m gradually becoming convinced that they’re not just “is” statements, but also descriptions of what always-already was the case.

It’s not just that the Grand Narratives have lost legitimacy, it’s that – as described – there never were Grand Narratives to begin with.

This may seem to be paradoxical: obviously, there was a thing called Christendom and a thing called the Eastern Bloc, and these things were examples of societies driven by Grand Narratives. However, can we say that these Grand Narratives held sway – that there was a time when one could hold up the Bible or Capital and say, passionately but without hope or aspiration that “this is the truth”?

Or did they just mean “this ought to be the truth”?

Look, just as nation states supposedly hold a monopoly on the use of violence within certain geographic borders, so to do ideologies – and religion is a form of ideology – supposedly hold a monopoly on the production of meaning – narrative – within a certain space. Oftentimes, there was an imperialist angle: it was necessary to expand the space in which a particular narrative is produced. This is written into the foundations of Christianity and, if my understanding is correct, of Islam. This does not mean that it is an inherent trait of all religions: Jewish people do not proselytize, and I believe the Parsis of South Asia discourage people from converting to their faith. Just as some states can be imperialist, some ideologies proselytize. I think that, in the Imperial Core, there is an expectation that ideologies seek to proselytize because we’re heavily influenced by our history.

But you might note that these Grand Narratives are always contested. Those who contest the state’s monopoly on violence are labeled criminals, and those who contest an ideology’s monopoly on narrative are branded heretic and revisionist, and oftentimes are subjected to violence as a result. These are people who promulgate divergent narratives, treated as foreign objects to be expelled.

Clearly, this had a historical start. We can point to times in Roman History, for example, when Roman soldiers left and joined barbarian tribes, and times when barbarians marched under Roman banners. There were even, if memory serves, people that did both at various times. The lines separating groups of people in those days were less strict – however, we can also point to the treatment of Alaric the Goth (the masterful book by Douglas Boin was reviewed by Edgar here and myself here) who betrayed Rome specifically for its treatment of his people, for their not being “Roman” enough, despite his prior loyalty.

And we can say that we live in a postmodern society, sure, but we must also acknowledge that this means we live in post-post-Christendom, and post-post-post-Roman world. These old ways of living are not wiped away, they’re overwritten, and these old ideas haunt the modern world until we specifically exorcise and expunge them. Perhaps the origins of heresy – at least in its secular form – lie back then. Perhaps earlier, I’m merely speculating.

The idea of the Grand Narrative has always been fragile to increases in communication. The Gutenberg press delivered a fatal blow to Christendom by making access to the Bible more general: this broke a portion of the narrative around the Catholic Church in Western Europe, leading to the various European Wars of Religion. This wasn’t the end of Christendom as a unified force, these were its death-throes. After this, various ideas – Liberty, Progress, the Working Class – were substituted for Christianity as the Grand Narrative. None of these are necessarily bad, mind you: I like the ideas of Liberty and Progress, I think we should try them, and in a thoroughly early-mid-21st-century way I am a member of the working class (though not, I should note, a member of the industrial proletariat).

As Grand Narratives, though, all of these failed. They may not have lasted as long as Christendom as a central idea, but they had more and more heresies popping up each time. More and more communicative technologies that hasten their ends.

So, could we look at the postmodern condition as being a sort of generalized, secular condition of heresy?

Not quite.

While I am postulating that the condition described above – that there never has been an authentic Grand Narrative (hence, the ugly assertion that “we have always been postmodern”) – might be true, I think it is important to realize that there is a difference between this fact and recognizing this fact. Social realities exist because of belief. As belief is invested into narratives and institutions, they appear to grow more powerful. As they actually do things, they legitimately grow more powerful. This confusion of image and reality, gesture and act, is precisely why the modern nation-state (specifically and especially the United States) is so sclerotic and useless. We have confused the gesture for the act.

Of course, one might argue that this is the logical outcome of postmodernism. If everything is a simulation, then it isn’t necessary to do anything, you just simulate it. This is precisely backwards.

Alongside Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals, I also acquired a copy of Saito Tamaki’s Beautiful Fighting Girl, a Lacanian media critique of a common character archetype found in Japanese Media. Alongside descriptions of the motivations behind using statuary as an onanistic aid (put in my best high academic to discourage people from googling things. Protect your eyes), there is some very insightful explanation of how Lacanian psychoanalysis can be used to analyze fiction, including the statement from the author that

media have no other function vis-à-vis experience than to provide this kind of consciousness of being mediated. Or to put it the other way around, “everyday reality” is nothing more than a set of experiences that emerge from a consciousness of not being mediated. This difference between a consciousness of being and not being mediated, moreover, is only an imaginary one. Let me emphasize this once more. For us neurotics “everyday reality” has no essential privilege. This is also evident from the fact that patients suffering from dissociative disorder (a neurotic pathology) experience everyday reality as if it were fiction. (p. 24)

In short, from a psychological perspective, reality and fiction exist on a continuum, and that there is a disjunction between the two when it comes to verisimilitude. As he notes slightly earlier in the book “One can easily imagine a paradoxical situation in which an autobiography overflowing with empty rhetorical flourishes might seem less realistic than a piece of honest metafiction. But the problem is more complex even than that. It may be, for example, that the rhetorical flourishes of that autobiography actually say something very real about the desires of its author” (p. 21).

Taken in alongside what was said previously, this suggests to me not that everything being a simulation (a vulgar read of postmodernism) that a simulated response to a real situation – a gesture as opposed to an act – is at all legitimate, but rather that we must understand the simulated as partaking in a measure of reality and reality always has a thin coating of simulation.

This is getting into the weeds.

What I intend to say is that it is not that nothing matters because there’s no meaning in the world; it’s that there is no transcendent meaning that organizes the world. No grand story of history that will play out to a logical end. Instead, what we have are the immanent, local stories that we encounter in our day to day life. Some of these – the story of Christ, the story of Liberty, the story of Progress, the story of the Working Class, the story of the Market – we elevate to a hegemonic place and act as if they are transcendent. What we ignore is that all of these gods have their feet in the mud, the same as the rest of us.

This fills many people with a sense of loss. Without a fixed point by which to navigate, how will we find our way through the vast and hostile wilderness of the future? If there is no story, simply a database of tropes that are expressed in epiphenomenal stories, how will we make sense of the world?

Ask yourself, instead, why you would impose the same story on every event you encounter. Let’s take it the other direction, let’s borrow some Deleuzoguattarian wisdom and accelerate the process. Take apart the tropes and pare them down to just moments of emotional intensity, vectors of feeling and meaning that encode nothing, and see what we can create from these elementary components.

What if we’ve just been playing in the shallow end of narrative, this whole time?

What if there is a deeper end of the pool that we could be exploring?

Where might we find meaning, if we decide to stop looking for it where we always have?

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.