A Close Read of The Ecology of Freedom, Part 2

The sunflower, a symbol of Green Politics in general, and of social ecology in particular. Generally speaking, it is also used as a symbol of solidarity with Ukraine, which is a connection we are aware of and generally comfortable making.

I am far from an expert on international affairs, and I’m not yet ready to do a book roundup of my own – which will be heavily featuring Japanese literature in translation, in pursuit of a semi-scholarly project I’m working on – so I’m a bit at a loss as to what to write. Hence, I’m going to be continuing my series on Murray Bookchin’s Ecology of Freedom, reviewed by me here, and the first part of this close-reading series can be found here.

As with the prior entry, this will largely consist of quotes I pulled from the book and wrote down, inter-cut with meditations on the text.

In the last piece, I finished on a passage where Bookchin begins to describe his conception of post-scarcity. As a reminder, this was less about the presence of infinite abundance, but about moving beyond the framework of thinking in terms of the world – nature in particular – being stingy. Given that this book was published a decade after Limits to Growth, a report commissioned by the Club of Rome (the international organization that similarly inspired John Brunner’s The Sheep Look Up, reviewed here,) which Bookchin, given his interests, could not have been ignorant of. This report conjectured, using computer modeling, that we would hit the limits of the Earth’s ability to support capitalist civilization within 100 years of the report’s compiling, which assumed that population, consumption, and production would remain static at then-current levels, which not only haven’t remained static but which could not remain static if the system hadn’t been changed.

One can easily see Ecology of Freedom as being a left-libertarian answer to the problems advanced by the Club of Rome – it’s easy enough to see the Authoritarian answers to the issue, but there is no ethical way to pursue those answers. It is only through re-envisioning the relationship between humans and our world that any way forward is possible.

So, let’s jump in to the text.

Bookchin continued this line of reasoning by explaining that:

In summary, it is not in the diminution or expansion of needs that the true history of needs is written. Rather, it is in the selection of needs as a function of the free and spontaneous development of the subject that needs become qualitative and rational. Needs are inseparable from the subjectivity of the "needer" and the context in which his or her personality is formed. The autonomy that is given to use-values in the formation of needs leaves out the personal quality, human powers, and intellectual coherence of their user. It is not industrial productivity that creates mutilated use-values but social irrationality that creates mutilated users. (emphasis added, p.70)

In short, he is discussing how many of the so-called “needs” that people try to fulfill are, in fact, socially constructed. For example, one of the main points of anxiety I hear people – including myself – discuss is fuel prices. However, this anxiety is the product of a mutilation at both ends of the equation.

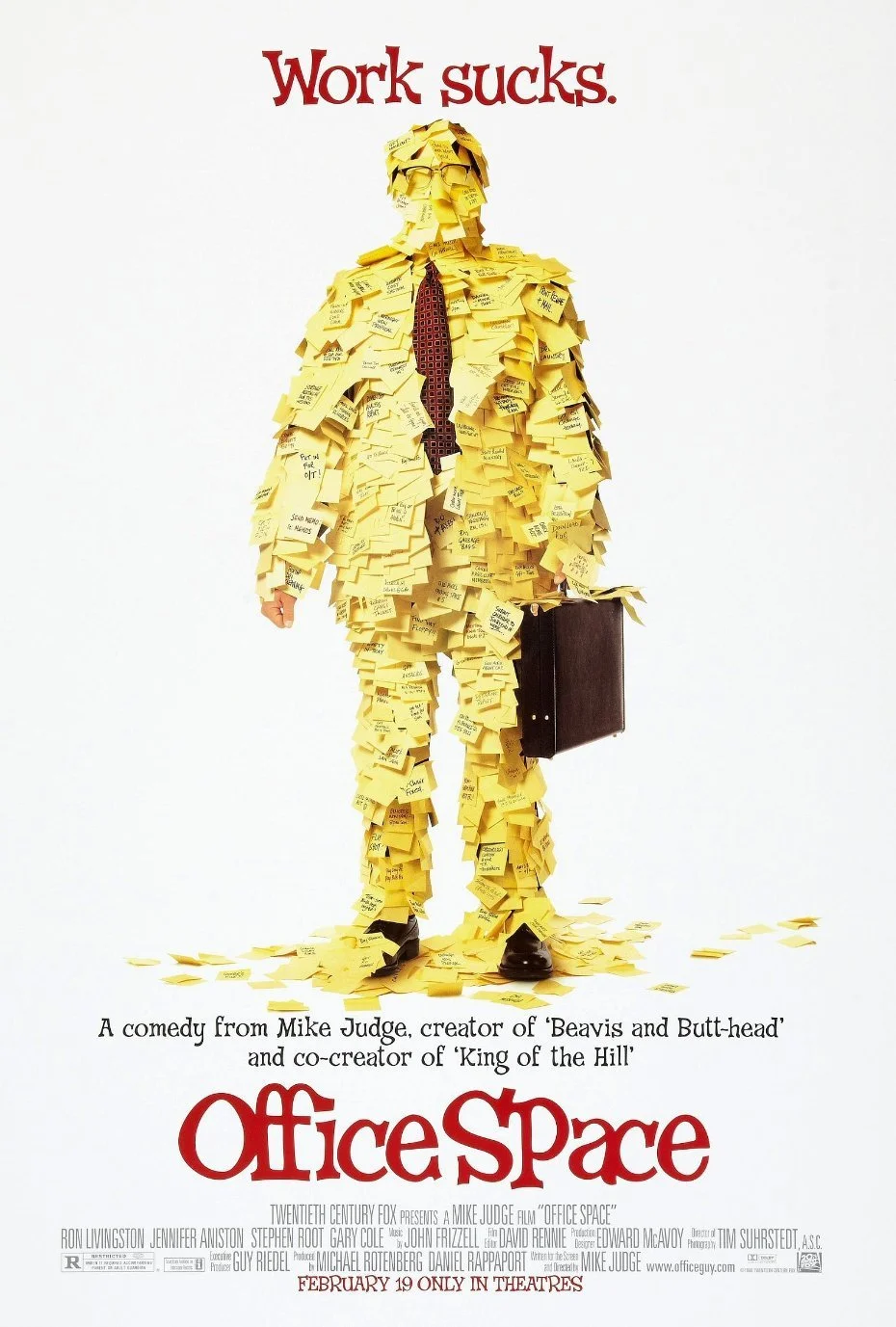

This whole situation is parodied in the movie Office Space, which is the Mike Judge movie that I’m still on board for. Idiocracy is a little reactionary.

Let’s limit our discussion to America, because the mutilation in question is most extreme there: the working culture of the United States is toxic for a variety of reasons, but one of the central ones is that absence from the location of work is in no way tolerated. This makes sense for some jobs – you can’t exactly be a bricklayer from home – but office workers are forced senselessly to be present in an office where they can be monitored, and service workers largely don’t have the ability to take time off and still support themselves: perhaps they might have sick days, but the likelihood of them being paid sick days is low, and if the worker relies on tips, then there is no possibility that they can survive an absence.

So, this means that they are required to be present, which necessitates travel. For many, this requires either the expenditure of a great quantity of time, or the expenditure of money and a smaller quantity of time. Given the limited conjunction of functional public transportation and need, largely this means buying gasoline to drive to work. However, gasoline is not the only thing one needs to pay for to drive to work – there is all of the regular maintenance and the various fees that surround driving that one needs to engage with to drive a car.

We are bringing back alternatives, but they’re generally novelties — Kansas City has a streetcar, for example, but it traverses a 2.2 mile North-South route that is not only reasonably walkable, but is already serviced by a free bus. It’s being expanded, but East-West expansion is not in the cards.

But on the other end, there is also the fact that we are not given suitable options to choose differently. How many people would prefer to bicycle to work, but lack the ability to due to local infrastructure making this a suicidal proposition? It is not industrialized society that has made the urban landscape the habitat of the automobile; that choice was made by actors within our society and has simply become so entrenched that we are prevented from choosing differently. This is what Bookchin means, I think, when he discusses “mutilated users” – people who are locked into one particular framework of assessing use-value. It is, in short, problem of inflexible – perhaps mutilated – epistemology.

Bookchin offers his own epistemology, which is perhaps the principle subject of the book, in all honesty. Let’s skip backwards in the text from the finishing point a bit and look more closely at it:

That nature is all that is nonhuman or, more broadly, nonsocial is a presumption rooted in more than rational discourse. It lies at the heart of an entire theory of knowledge — an epistemology that sharply bifurcates into objectivity and subjectivity. Since the Renaissance, the idea that knowledge lies locked within a mind closeted by its own supranatural limitations and insights has been the foundation for all our doubts about the very existence of a coherent constellation that can even be called nature. This idea is the foundation for an antinaturalistic body of epistemological theories. (p.38)

So here, I’m going to take a break and discuss knowledge – this will loop back around to the discussion of mutilated users, as well as the quote above, don’t worry. Aristotle defined knowledge as a “Justified, True Belief” (JTB), though I won’t be getting into the issue of Gettier Problems. Look into that issue on your own time.

The establishment of the Renaissance paradigm of knowledge can best be seen in the late medieval period, when Paracelsus rejected tradition as a source of authority in the interest of examining other sources — exemplified by publicly burning the works of Galen and Avicenna.

The issue here is that the Aristotelian construction of what knowledge is – which is very closely aligned with the “knowledge lies locked within a mind closeted by its own supranatural limitations and insights” description provided in the prior quote – doesn’t make a distinction between constructed and unconstructed knowledge.

You know that if you do not eat you will starve. You also know that if you do not show up for your shift on time you will be fired. Both of these are, perhaps JTBs, but the second one must be acknowledged as contingent: if all clocks in the world stopped working, there simply wouldn’t be a 9AM to show up for anymore. As much of an edge case as this is, clock-time doesn’t actually exist in nature. Perhaps this isn’t a useful thing to think about, given the prevalence of clocks, but one must acknowledge that one thing is socially constructed and the other is not.

Which brings up an issue with social construction: it doesn’t mean fake, it means emergent. Things that are socially constructed are not inherent to nature, they are emergent properties of nature, because human beings are – and stop me if you’ve heard this one – not separate from nature. The issue is that we can easily construct these things differently. It’s simply that those who have social and economic power instantiate hegemony: they arrange things to benefit them, generally to the detriment of others (see the above links, describing the GM Streetcar Scandal).

In short, we have justifications for false beliefs foisted upon us, but the justifications take place on what we might call the “supply side”: it’s not that taking public transportation to work is a bad idea, it’s that the people who control the public transportation infrastructure make it as hard as possible for you to use it. It’s not that riding your bike is a bad idea, it’s that all of the infrastructure is built for machines that can and will kill you if something goes wrong. It’s not that there is no alternative, it’s that all of the other alternatives have been sabotaged.

Let’s jump ahead. Bookchin writes:

As I have argued for years, the State is not merely a constellation of bureaucratic and coercive institutions. It is also a state of mind, an instilled mentality for ordering reality. Accordingly, the State has a long history — not only institutionally but also psychologically. Apart from dramatic invasions in which conquering peoples either completely subdue or virtually annihilate the conquered, the State evolves in gradations, often coming to rest during its overall historical development in such highly incomplete or hybridized forms that its boundaries are almost impossible to fix in strictly political terms. (Emphasis mine, p. 94)

Chinese economics was chartalist from almost the very beginning — hence the development of paper money in the 11th century.

As a brief aside: there is a tendency in the neoliberal period to articulate an opposition between state and market, but this opposition rests upon the largely discredited metallist theory of money – the thinking that, to put it vulgarly, that there is an inherent “money-ness” to things like gold – as opposed to a potentially more accurate Chartalist theory, which argues that the state of being a currency comes from the use of a certain commodity to pay taxes (this is part of why cryptocurrency isn’t actually currency, but simply a pyramid scheme – there’s no differential pressure on the system to make the currency circulate.)

This means that one can see the actions of the state and the market as being different but entwined – there’s a strange sort of correspondence, a recursive puppetry to the behavior of state and market where the one influences the other. So, to continue with the example used previously, one can see the GM streetcar scandal issue as arising from the fact that the laws were established in such a way to allow this situation to unfold in the fashion that it did, which means that it’s result of the actions of the state-market complex.

An early shipboard clock.

However, what this means for us as individual people is that certain habits of mind are inscribed upon us, etched into the folds of our brains. Things like the value of the dollar, like clock-time, and like the importance of the price of gas are inculcated in us as we grow, because while these things are not inherently important, a failure to abide by them will result in great difficulty at some point or another. In short, though invented, awareness of these things is made into knowledge by the presence of a coercive apparatus: a machine of human will that mutilates us into the shape we are “supposed” to take. Of course, one could see a class differentiation present here that maps loosely on to the Marxist one, though I’m personally inclined to see it in different terms: those of agency.

Let’s jump further ahead:

With the hollowing out of community by the market system, with its loss of structure, articulation, and form, we witness the concomitant hollowing out of personality itself. Just as the spiritual and institutional ties that linked human beings together into vibrant social relations are eroded by the mass market, so the sinews that make for subjectivity, character, and self-definition are divested of form and meaning. The isolated, seemingly autonomous ego that bourgeois society celebrated as the highest achievement of "modernity" turns out to be the mere husk of a once fairly rounded individual whose very completeness as an ego was possible because he or she was rooted in a fairly rounded and complete community. (emphasis mine, p. 137)

This is, in many ways, the counterpoint to the Lyotard passage that loaned its title to my last Mark Fisher piece “Hang on Tight and Spit On Me”, which I will quote here for its use as a counterpoint:

[T]he English unemployed did not become workers to survive, they – hang on tight and spit on me – enjoyed the hysterical, masochistic, whatever exhaustion it was of hanging on in the mines, in the foundries, in the factories, in hell, they enjoyed it, enjoyed the mad destruction of their organic body which was indeed imposed upon them, they enjoyed the decomposition of their personal identity, the identity that the peasant tradition had constructed for them, enjoyed the dissolution of their families and villages, and enjoyed the new monstrous anonymity of the suburbs and the pubs in the morning and evening. (Libidinal Economy, p. 111)

There is a part of me that wants to write a monograph putting these two passages into tension with one another and exploring the interplay between them, because the tension between them isn’t simply an opposition, it is, I think a dialectical tension: there is a synthetic combination between the two concepts waiting to come about.

Because the bourgeois ego that Bookchin describes (see the bit about Odysseus later) is a mutilated thing, disembedded and subjected to horrible mistreatment. But, at the same time, it was not resisted except by isolated anomalies. By and large, the ex-peasants of the early industrial era did not engage in outright revolt, but leaped into the jaws of Blake’s “Dark Satanic Mills” to become the industrial proletariat.

My own understanding here is that, with the loss of the Feudal medieval logic and the implementation of such social institutions as mercantilism and early capitalism, it was assumed that anyone could become wealthy like a feudal lord; all that was needed is the acceptance that many would die of social murder. But all that was needed was for a generation to be educated with this system naturalized.

Consider:

The nobles of the Odyssey were an exploitative class — not only materially but psychologically, not only objectively but subjectively. The analysis of Odysseus (developed by Horkheimer and Adorno) as the nascent bourgeois man is unerring in its ruthless clarity and dialectical insight. Artifice, trickery, cunning, deception, debasement in the pursuit of gain — all marked the new "discipline" that the emerging rulers imposed on themselves to discipline and rule their anonymous underlings. "To be called a merchant was a grave insult to Odysseus," Finley observes; "men of his class exchanged goods ceremoniously or they took it by plunder." Thus was the primordial code of behavior honored formally. But "valor" became the excuse for plunder, which turned into the aristocratic mode of "trade." Honor had in fact acquired its commodity equivalent. Preceding the prosaic merchant with goods and gold in hand was the colorful hero with shield and sword. (p. 146)

A Roman-era bust of Odysseus.

I read this in conjunction with The Dawn of Everything by Davids Graeber and Wengrow, which examined the origins of heroic societies and proposed that they had a separate origin in the hinterlands of earlier, more libertarian city-states, attaching themselves like the cordyceps fungus to these other social formations. The heroic figure of Odysseus might have been adopted as a sort of totemic figure by the bourgeois: the cunning hero that raids and takes what he needs, translated and transposed to the industrial world, becomes the model of the contemporary bourgeois ego.

However, what you also have is the democratization of tyranny as a concomitant development – best exemplified by the farcical recapitulation of the Odysseus-figure in modern society, the small business tyrant. These people, the owners of small businesses who have supposedly achieved the American Dream, are an expression of this transformation, all wound-down and lacking in the heroic dimensions attributed to them by the mythic origin, but fully claiming the honor supposedly due to them – the resistance to lockdown and mask mandates in the United States are largely the result of these people, who saw themselves as an army of heroes standing against tyranny. It all boils down to a warped assessment of the value of human life, where they are viewed as the “most human” and thus, whose lives are somehow the “most valuable”.

Bookchin writes:

It is not the ethical calculus that comprises the most vulnerable features of utilitarian ethics but the fact that liberalism had denatured reason itself into a mere methodology for calculating sentiments — with the same operational techniques that bankers and industrialists use to administer their enterprises. Nearly two centuries later, this kind of rationality was to horrify a less credulous public as a form of thermonuclear ethics in which varying sums of bomb shelters were to yield more or less casualties in the event of nuclear war. (p. 165).

Image taken from a Vox article on the issue — note that this sort of expensive gear is generally too expensive for an hourly worker to afford. These anti-lockdown protests are thus best understood not as a “working class” protest, but as a revolt of petite-bourgeois, based on a perceived threat to their status.

This is the apotheosis of the “mutilated user”. The person whose ability to assess the value of human lives is reduced down to their assessment of the use-value of those people. Because these people are viewed as the normative individual, all other people who haven’t achieved this status are viewed as somehow the larval form of this type of individual. However, if the mutilation is incomplete then it leads to failures: many small businesses are, of course, failures due to maladroit management, but it also stands to reason that a fair number of them failed because the mutilation was incomplete, because they couldn’t simply reduce their employees to numbers on a balance sheet.

The answer here is to alter our relationship to our wants and needs, to move into a post-scarcity mindset and take ownership of our relationship to the world. The particulars are still unset, and need to be measured and weighed, but the question is not whether this should be done, but how.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates, and a bookshop, where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)

If you’re interested in reading more about Murray Bookchin and his thinking, and don’t want to wait for me to gather more quotes, you can learn more about the concepts here by visiting the website for the Institute for Social Ecology.