Testosterone is a Hell of a Drug: Masculinity and Authoritarianism

Oh, how exhausting it is to live through history. Shinzo Abe shot in the back, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa of Sri Lanka flees the country because of unrest, and Boris Johnson overseeing the largest mass resignation in the British government, ever. All in all a bad week to be proximate to power in an island country with a history of nationalist and colonial violence. Closer to home, there was a major gun violence event in Kansas City recently (a shooting at a bar in one of the entertainment districts). Slightly more broadly than that, the United States overturned Roe vs. Wade, and we continue to be a seething mess of gun violence and climate change.

Now, there are many possible causes for all of this unrest. I am not going to claim that there is a singular definite cause for everything happening right now: however, I do think that there is an accelerant that all of the sparks of these various problems are landing upon.

Leaving aside the various heads of state, the issues of gun violence and abortion access might not seem connected, but it seems to me that both hinge upon the way that masculinity is constructed in the hegemonic culture.

I’ve written a number of pieces about masculinity in the past. However, it seems to me that masculinity is extremely hard to pin down an actual definition of: what is masculinity? How do you define it?

This is a nearly pure example of what I’ve called the “Unmarked Default” in the past. Because masculinity is positioned as the thing from which other gender expressions are deviations, masculinity gets away with being fundamentally without definition. It’s somewhat like saying that masculinity is blue, while defining other gender presentations as being periwinkle blue, sky blue, navy blue, Prussian blue, cobalt blue, cornflower, cerulean, zaffre, ultramarine, and indigo. Of course, in the dominant construction, there’s just two options, and only one of them gets a definition.

So, while it might be possible to describe what color “navy blue” is, it’s much harder to describe what “blue” itself is.

There is, however, one generally acknowledged trait of masculinity: there is an inherent connection between masculinity and authority. While it isn’t impossible for a feminine individual to wield authority, in the eyes of most (or the big other), this happens in spite of that person’s femininity, not because of it. With a masculine leader, it’s commonly seen as more congruent.

Pictured: leadership, decisiveness.

Some might see this as natural: testosterone, the “male sex hormone,” supposedly associated with an increase in status-seeking behavior. The more “manly” one is, supposedly the more obsessed with one’s place in a perceived pecking-order, and seems to have a greater effect on those with an unstable or low social status. In the vulgar understanding that most have of the issue, greater levels of testosterone translate 1:1 with greater “manliness,” which is associated with strength, aggression, stoicism, decisiveness, and leadership. Hence all of the people out there looking to make a quick buck selling means of increasing testosterone, especially attempting to appeal to the audience for AM radio pundits.

These same traits, as many have noted, are associated with “bitchiness” for women. I’m not going to rehash the feminist critiques of patriarchy, but I do think it is useful to understand what they are: especially because insisting that men need to display the traits that are associated with masculinity effectively requires young boys to amputate their emotions, leaving behind a stump of anger and similar negative emotions.

We should note that Foster Wallace was credibly accused of stalking and harassing women. Genius in one area doesn’t make you good at being a person, and we have to acknowledge what he did wrong to use his work.

(Image taken from wikipedia, originally uploaded by user Steve Rhodes. Used under a CC BY 2.0 license.)

The masculine ideology, when made explicit, becomes a treadmill: you must always be stronger, more stoic, more decisive, more of a leader. However, no one really knows what leadership is. By pursuing these things, you end up trapped inside your own lack. Consider what David Foster Wallace – himself a man trapped by his own demons and appetites – said in “This is Water,” a commencement speech he gave in 2005 to the graduates of Kenyon College:

This, I submit, is the freedom of a real education, of learning how to be well-adjusted. You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t. You get to decide what to worship.

Because here’s something else that’s weird but true: in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship–be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles–is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally grieve you. On one level, we all know this stuff already. It’s been codified as myths, proverbs, clichés, epigrams, parables; the skeleton of every great story. The whole trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness.

Worship power, you will end up feeling weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to numb you to your own fear. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart, you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out. But the insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful, it’s that they’re unconscious. They are default settings.

I tend to make my students read this at the end of each semester, to send them into a restful period with something to think on. What we obsess over is what we inevitably find ourselves lacking in, because that’s the nature of obsession – of worship – even the wealthiest person, should they worship the dollar, will feel insecure in their billions; even the most intelligent will be tortured by their ignorance; even the most prestigious will hear a derisive laugh aimed at them.

The character of Ron Swanson (Nick Offerman), from Parks and Recreation, paddling a canoe. Swanson is an interesting character — he’s an affectionate parody of hypermasculinity, and in reality would probably more closely resemble Jordan Peterson than anything else, but it’s the character’s status as a parody that allows him to be beloved: the contradictions in the character don’t cause discord, they’re the point of the character.

So, those who worship manliness, it seems to me, feel their grip on that identity is too loose. It is not enough for such people to perform manliness, they feel that they must consume it, and let it consume them from the inside out, subsuming everything they are to what they believe it to be.

Consider the stereotypical cismasculine obsession with manliness uses technologies perfected for transgender people, while also tending rather strongly to fear and loathe transgender people. I’m sure that there are gay men who have other experiences of it, but from where I’m sitting, the people most likely to be obsessed with manliness are those most likely to hate queer people, and yet they now use those tools to try to increase the intensity of this thing that they think is most important.

But none of them can offer a coherent picture of it, because to say it out loud is to kill the thing you’re pursuing. The experience of masculinity is disavowed vulnerability. You’re always worried about losing the status of being “a man,” but you can never say as much.

I had this theory I developed in college, when I noticed those around me behave like idiots after drinking three beers, even though I only ever seemed to get clumsy and unselfconscious. Because we had these images of how “the drunk person” behaves, people would adopt these images as their guidelines when they drank. They would play the part of the stoner when they smoked cannabis, or the part of the cokehead when they did a rail. This is not to say that these drugs had no effect, but they leaned in when they consumed the narcotic.

These days, I live with a transgender person – Edgar is on hormones, and I’m not going to pull an Argonauts and talk as a cis person partnered to a trans person about the trans experience, but I am going to summarize what they said about their experiences and invite them to write on them in the future – and in our discussions, we’ve noticed something. Testosterone hasn’t produced wild personality shifts or increases in aggression and status-seeking behaviors. There have been some changes, but these changes are largely the result of physiological shifts making certain patterns of behavior more comfortable or rewarding.

So here’s my theory: people behave as they do on narcotics partially because they have an image of how people on that narcotic act; for purposes of this discussion, sex hormones function the same way.

Simply because our bodies already produce testosterone, estrogen, oxytocin, and other hormones doesn’t mean that they can be considered inherently differently from other things that work on us – after all, for a narcotic to have a short-term effect, it has to work on organs already present and which have evolved to respond to certain stimuli. Famously – and purportedly – the hallucinogen DMT is produced endogenously by the human brain when dreaming or dying.

What does this mean?

Simply speaking, gender is an ideology that people follow. It is also a role that they perform and an image that they attempt to match.

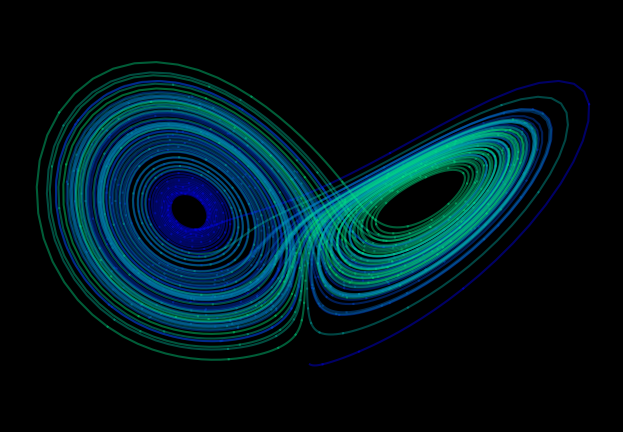

The Lorenz Attractor, viewed from a variant angle.

Everything considered “unmanly” has been foisted off into femininity – caring for others, for example – and with the procession of women’s rights and queer rights more and more has been peeled off from masculinity, until we’ve been left with what’s at its core: a disavowed vulnerability, shielded by a capacity for violence and little else. It is a strange attractor, invisible, but bending the course of our desires around it.

This emptiness doesn’t just play out in the dialectic between the sexes, it also reaches beyond it. This may be the most contentious point that I’m going to make here: the hegemonic construction of masculinity – and those deriving from it – are inherently authoritarian.

Consider Cara Dagget’s piece “Petro-masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire,” which attempts to describe one strain of reactionary masculinity that has become dominant on the American right wing. She writes that:

Psychological studies of authoritarianism in the 20th century are best taken as narratives of specific historical movements, rather than as universal scientific truths. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify patterns. One of the most consistent themes that runs across Western authoritarian movements is a widespread sense of gender anxiety – especially having to do with masculinity. Patriarchal ideals are manically proclaimed (by adherents who identify as women, too), but beneath the obsession with hyper-masculinity reveals an underlying fear of the social fragility of masculinity, as well as a shared sense among members of each having personally fallen short of that ideal. Capitalist crises, such as the worldwide depression of the 1930s or the 2008 financial crisis, do not help; they only make it more difficult for many to achieve that essential emblem of modern masculinity: a breadwinner job. The Authoritarian Personality notes that ‘high-scoring’ men (those with more authoritarian traits) ‘show deep-seated fears of weakness’ in themselves. The meaning of weakness to these men seems to be tied up with intense fears of nonmasculinity. To escape these fears they try to bolster themselves up by various antiweakness or pseudomasculinity defences, where pseudomasculinity means ‘boastfulness about such traits as determination, energy, industry, independence, decisiveness, and will power’.

Gender anxiety – or a sense of masculine weakness – is intertwined with another common trait of the authoritarian character: sadomasochism. After all, masculine displays of strength and independence would seem to be at odds with unquestioning submission to an authoritarian leader. But as Fromm argues, ‘the lust for power is not rooted in strength but in weakness … It is the desperate attempt to gain secondary strength where genuine strength is lacking’. In other words, sadomasochism reflects a desire to overpower others that is aroused by, and at the same time stymied by, one’s own sense of impotence. The failures of fossil capitalism to sustain its white masculine order, which it helped to erect, with wages and commodities, only exacerbates the sense of collective impotence. In order to manifest power, the impotent, authoritarian personality is forced to subsume its urge to dominate within submission to a stronger external force, be it God, the laws of the market, the military leader, or a tyrant. Or fossil fuel burning.”

(footnotes from the original have been removed; I highly recommend reading it, it’s an absolute banger of an essay.)

Personally, I don’t get the attraction. Uploaded to wikipedia by Salvatore Amone and used under a CC BY 3.0 license.

I’m going a step beyond what Dagget said in her piece, though: while, as she notes, masculinities are always multiple, she claims that what she refers to as petro-masculinity – a heavily masculinized fascist ideology obsessed with fossil fuels – is a masculinity, contrasted to its close cousin “ecomodernist masculinity” among others – I would argue that the difference between these is the same as between a coal-rolling truck and a Prius. One’s obviously less harmful, but they’re fundamentally the same and run off the same fuel.

A long time ago, I pointed out that I’ve never heard of an individual who was both an anarchist and an incel – to be an incel, I think, is to have a heavily gendered and heteronormative authoritarianism as your north star – and what I’m saying here is an extension of that. There is a fault in our construction of masculinity that leads to authoritarian thinking.

Now, before you scroll down and start leaving angry comments, let me add a wrinkle: I don’t think this is inherently the case. I think that it is entirely possible to be masculine and anti-authoritarian. I see this tendency in my transmasculine partner and friends, for example, though I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s inherent to people who adopt that identity – my constant discussion of the dangers of essentialism should convince you of that.

What is necessary here is eliminating the disavowed vulnerability: dragging it out into the light, and letting it burn like the vampiric lack that it is. I don’t think that I’m leading the way here, instead I want to try to point at places where this is already being done.

The first album of theirs that I listened to, People Who Can Eat People are the Luckiest People in the World. An excellent entry point.

While their music isn’t for everyone, I do think that the music of the band AJJ (formerly, and thankfully no longer, called “Andrew Jackson Jihad”) shows some of this in the lyrics of front man Sean Bonnette, who vacillates between a kind of abject masculinity, seething rage, and an exhausted care for those around him, as if he’s triangulating the boiling point between two ways of performing masculinity and trying to draw the line so that others can step over it.

Matt Bell’s Appleseed (reviewed by Edgar here) and which will be showing up in my next book round up shows some of this in the portions written about the character Chapman, who is meant to be the historical Johnny Appleseed: as time passes, Chapman learns that the natural world is not infinite and that his appetite to transform it into a site for the fulfillment of his own desires is a misstep and a tragic overreach. Chapman’s regret and reflection upon this suggests the beginning of a move towards a different, divergent state, which is an important thought experiment: if he had survived, and embraced the wild nature he spent so long denying, how might he have been different? The reduction of the natural world into a mere means, based on an ideology of utility was the cornerstone of settler masculinity, and its ghost still haunts us.

These alternative and variant masculinities that are in conversation with the central lack, the self-destructive core of what I’ve been calling hegemonic masculinity, can serve as tools to map where we are, and hopefully help find where we can go to escape it.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.