"Where I'll Be, Not Where I Was": Ezra Furman's Transformations

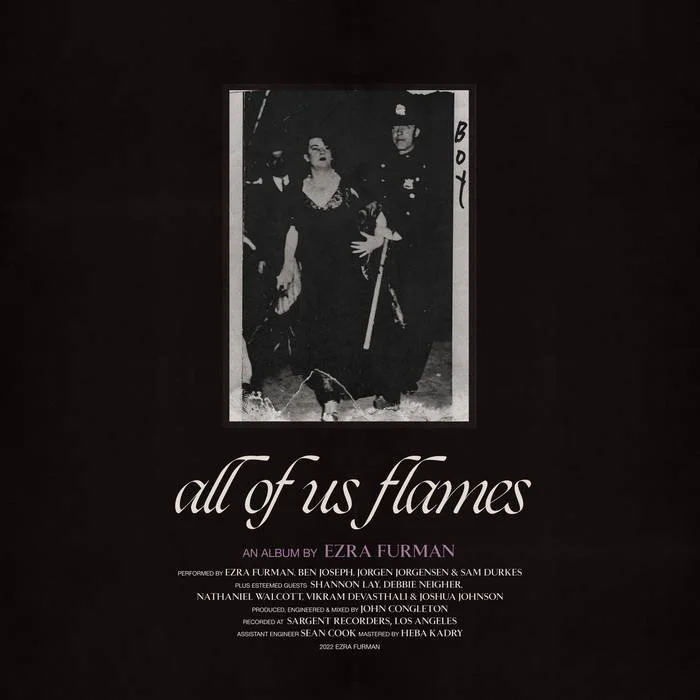

The cover of All of Us Flames, which I took from Furman’s Bandcamp, along with the other album covers shown in this piece.

For dumb bullshit reasons, I didn’t get to listen to Ezra Furman’s latest album, All Of Us Flames, until it had already been out for almost a week. I was excited, not only because Furman’s recent output has been increasingly stellar, but also because a number of people whose taste I trust praised it highly: poet Hanif Abdurraqib described the songs as “touchable” in an Instagram story post; Holly Hazelwood, in her review for Spectrum Culture, wrote, “… the listener can feel like their queerness isn’t a death sentence — but, rather, it’s something that you can grow old with.” Needless to say, I was excited.

But I sometimes get a little too caught up in whether I can actually how much better something sounds from my ten-year-old computer speakers than it does from my cheap headphones or — horror! — jangling out of the built-in speaker on my phone, so I didn’t get to listen to it right away. Also I had to work. Also also I’ve been increasingly overbooked, but that’s neither here nor there. Also also also I try not to get too excited about new stuff, if I can help it: there are let-downs, and times when I’m just not in the mood for the energy of a given album (or book or movie), and it’s not fair to me or the thing to push through when I’m not feeling it.

So excitement and trepidation! A heady blend, and one that Furman understands well: it’s been a major theme of several prior albums, and that carries on in to All Of Us Flames. But isn’t that the proper affect before any transformation?

※

I write this having yesterday appeared in court to effect a legal name change. The laws surrounding this process are antiquated, largely hinging on ascertaining whether or not you’re doing it to escape your creditors. I’ll have to put a notice in a newspaper, is how antiquated we’re talking. I started taking testosterone earlier this year. My hair — the parts I haven’t shaved, at least — is longer than it’s been in years.

Obviously, none of this happened overnight: contrary to what transphobes will tell you, “rapid-onset gender dysphoria” doesn’t exist. What does exist is learning words, and understanding how they may describe feelings that you have — feelings otherwise swept to the side, characterized only as, say, “bad” or “weird.” And even when you have the words, understanding how they apply is a step still further.

Had you asked me, when I was first coming to accept my transness, if I had dysphoria, I would — and did — waffle a bit and say, “No, not really.” I thought I was telling the truth, too, and that many of the feelings, or lack thereof, that had characterized my life were due entirely to other things. It is only as I’ve been able to reconcile my physical being to my experience of my gender that I’ve come to know how much I was setting aside neatly, meat in a cardboard box, deliquescing.

And that sensibility, that feeling that you’re fine, really, just that you feel bad all the time and sometimes it just feels like the walls are closing in and you’re doing to die, but it’s okay — that feeling, or set of feelings, made pretty frequent appearances on Furman’s albums. Songs like “I Wanna Destroy Myself” from 2013’s Day of the Dog and “Watch You Go By” from 2015’s Perpetual Motion People dress up despair and abjection in, respectively, a catchy, garage-y tantrum and a mild-mannered doo-wop torch song. The hopelessness evinced in both songs exemplifies a kind of blind grappling with feeling, with the sense that something is wrong here.

But when those songs came out, Furman seemed to still be arriving to herself: she fronted Ezra Furman and the Harpoons until 2011, and then began releasing solo albums, solidifying the touring band that has been with her since Day of the Dog under various cheeky names (the Boy-Friends, the Visions). That touring band is credited on the front cover of All of Us Flames under their own names, along with the producer and many of the other personnel, and I think there’s something in that — something that points to what All of Us Flames is doing, and why, and how.

※

The perfectly evocative cover of Transangelic Exodus.

Furman named the great terror and the great joy in 2018’s Transangelic Exodus. I, personally, did not shut up about it for months, and settled in to describing it as an album that vibes like the Frankie Goes to Hollywood cover of “Born to Run.” I stand by that descriptor, but in hindsight, with the lenses of Furman’s two subsequent albums, it’s easy to see the terror of being out — like, out-out — and the way acceptance of the self is almost always attended with total flensing of the self. While much of Transangelic Exodus is joyously defiant — “Suck the Blood from My Wound,” as an opening track, no less, comes immediately to mind — others are almost excruciating to listen to. “Come Here and Get Away from Me” is a tough sit, a vicious little song that speaks very directly to a need for connection coupled with absolute internal hell: “There’s a plague in my head,” she sings, a bitter hiss to her voice, over a sneaky little guitar line, and, later —

I believe in God

But I don't believe we're getting out of this one

Before somebody pays for the things I've done

I did some terrible things it's true

But even terrible-r were the things I didn't do

And that’s not even touching on “Maraschino Red Dress $8.99 at Goodwill.” I saw Furman when she was touring this album; she seemed sad-nervous and kind of stoned, which did not at all detract from her or the band’s performances. She introduced “Maraschino Red Dress” as being a song about hating yourself — she put it more eloquently than that, but that was several years ago, and I’ve done my share of self-destruction in the interim — and that came through both in the performance and in her lyrics: “Sometimes you go through hell and you never get to heaven,” delivered in a shivering, spiteful voice that lingers on the never, hits like a slap, and the musical bed is jaunty to the point of being frantic.

Furman’s rage turned outward, though, in the follow-up to Transangelic Exodus, 2019’s Twelve Nudes. Furman was relatively circumspect in interviews, though as Paper magazine put it:

The frankly distressing cover of Twelve Nudes.

Furman didn't set out to make a protest album. Rather, she says she tried to think about "what is concerning me on the deepest level and make an album about that." As a trans woman and observant Jew, Furman's daily anxieties have political implications.

Fader adds: “Twelve Nudes posits that being in pain just sucks — not so much an escape as a confrontation with how everything is not OK and that it's OK to say that out loud, too.”

So let’s take as an example “My Teeth Hurt” (which just so happens to be my favorite song on the album). Over a crisp, jangly musical bed anchored in a simple but precise drum line, Furman sings about the all-consuming quality of tooth pain when you don’t have insurance, allowing the sentiment to metastasize into a broader — but no less catchy — reflection on pain along the emotional and social axes, as well as the physical: “I refuse to call this living life and I refuse to die,” at the close of the first verse; “the ache inside reminds my mind my body's really there,” and, “when pleasure lets you down you learn to lean into the pain,” in the second; “I don’t know how I’m doing lately / Fuck you if you ask,” as a sort of bridge. It’s a deceptively straight-forward tune that expands and twists under contemplation.

※

So that’s the first two installments, following the trilogy-structure advanced by Hazelwood — and I do love a narrative arc to an artist’s oeuvre, so I’m inclined to stick with it. What’s up, then, with this third part, so new to the world and my personal rotation?

Sonically, it’s much more laid-back than either of its predecessors: while Furman is scarcely a chill artist, she seems more self-assured, less nervy than on prior albums. In the slow horns of “Point Me Toward the Real,” the subdued throb of a finger-picked guitar in the intro of “Temple of Broken Dreams,” in the reverberating piano notes of “Book of Our Names” — musically and lyrically, there are fewer spitting hissy-fits and more crooning, a shift from I to we, as noted in The Guardian. Elsewhere, the same article offers:

“I was trying to [say], there is no end of the world,” Furman explains, sipping a small beer in a quiet garden in east London. It is a few days after the UK’s first bout of extreme heat, when record-breaking temperatures left parts of Essex on fire and bin bags melted on the pavement, and a sense of doom hangs in the air. “Your rights being taken away by the government is not the apocalypse. Not being able to buy food at the supermarket any more is not the apocalypse. Or maybe it is – but then we’ve got to figure out how to grow food ourselves and bring it to our neighbours. We’ve got to keep taking care of each other.”

The cover of the single version of “Point Me Toward the Real.”

And here’s the plot twist in this one: where Transangelic Exodus and Twelve Nudes offered a very inward-oriented approach, All of Us Flames focuses much more on deep friendship and community. As others have noted, Furman explicitly labelled herself a mother as a community gesture when she came out as a trans woman last year, and did it explicitly to offer an example of possible futures for other trans people.

That is, I think, a key part of what All of Us Flames seeks to do, as Furman has noted. What’s absolutely thrilling is how very, very well she does it. In these songs, she offers dreams the Furman presented in Transangelic Exodus couldn’t have named, deep connection and care that the singer of Twelve Nudes wouldn’t have dared to hope for. Many of these songs are defiant, many are sad, but All of Us Flames is focused very intently on trans life, in all its beauty. It’s a gift of an album, firm and tender, and I’m so happy to get to listen to it, and to get to celebrate my own transness, my own queer community, as Furman celebrates hers.