The Turing Fallacy: On Art in the Age of Its Algorithmic Generation

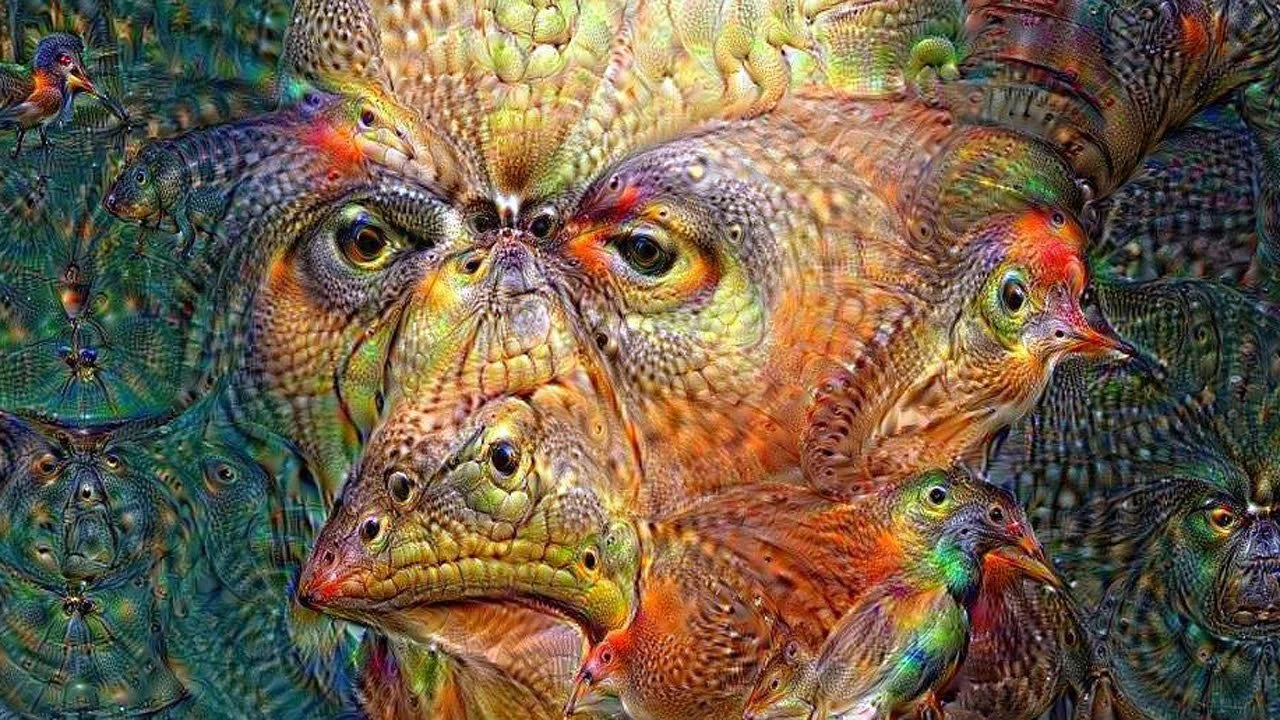

We could have avoided this if we’d all just decided we didn’t need to mess around with Google Deep Dream.

I’m taking a break from prepping this coming semester to write this, though I know that – if I do such things – I need to get away from my computer and look at something that isn’t a screen. Still, Wednesday is Wednesday, and I’m doing better than I really have any right to be as far as prep goes.

I wanted to talk about what I previously referred to as “the Turing Fallacy.” This was – it seemed to me – a snappy way to summarize something that I touched upon very briefly a long time ago. Needless to say, hack that I am, I took the time to google the term and found that there was a real thing called the “Church-Turing Thesis” and a corresponding “Church-Turing Fallacy.” I saw it explained a number of ways, and I’m not really interested or qualified to talk about the mathematics of it – what the hell is a Turing Machine? I don’t know, my reading the past week has been largely dominated by Terry Eagleton’s How to Read a Poem, which I think should exempt me from mathematics-related discussions, but I’m forcing myself into this one.

Still, the most cogent explanation I’ve found is from Neurocognitive Mechanisms: Explaining Biological Cognition by Gualtiero Piccinini, found in Chapter 10 of that book. In the abstract of this chapter, Doctor Piccinini wrote that:

The Church–Turing thesis (CT) says that, if a function is computable in the intuitive sense, then it is computable by Turing machines. CT has been employed in arguments for the Computational Theory of Cognition (CTC). One argument is that cognitive functions are Turing-computable because all physical processes are Turing-computable. A second argument is that cognitive functions are Turing-computable because cognitive processes are effective in the sense analyzed by Alan Turing. A third argument is that cognitive functions are Turing-computable because Turing-computable functions are the only type of function permitted by a mechanistic psychology.

Fundamentally, this means asking whether a mechanistic computation and a biological thought are the same thing. I have some issues with this, but let’s take it at face value for a moment.

I don’t know how big this is, but it looks really big. The fact that it takes about enough electricity to power 10,000 suburban homes says a lot. You can read more about the simulation here.

The most impressive brain simulation I was able to find any mention of was performed in 2013, using the K Computer, the world’s (then) 4th fastest supercomputer. The operation took 82,944 processors and 40 minutes of time to simulate 1.73 billion nerve cells connected by 10.4 trillion synapses. This yielded one second of usable simulation of one percent of a human brain (and leave aside that “you only use X percent of your brain” bunk – you use the whole thing, it’s just that “using” it requires a lot of it to be doing sub-conscious activities most of the time. Or do you really want to always be thinking about the position of your tongue in your mouth?)

So, even if we accept this as a valid simulation (it mapped physical changes within the neurons and the pattern of activity between them), it’s 1% of 1 second of brain activity. If Moore’s law held true, and we accept the most vulgar read of things, we could expect a similar modern simulation to be about 32% of the human brain and happen much faster – which I’m pretty sure is incorrect.

I’m not convinced though, that thoughts are necessarily just the activities of the brain. Leaving aside the role of the whole human body in the course of thought, this could be something like assuming that you can tap into the wifi with a transistor radio or power your car with crude oil. How do we know that the neural event isn’t just a carrier for another phenomenon that the neurons can interpret as a collective, but which would be opaque to an MRI or PET scan?

Perhaps I’m being too much of an idealist here, but it really seems to me that thought and computation aren’t necessarily the same thing, and it would be a mistake to confuse the one for the other. I’m not saying this to say that we’ll never create a sentient or cognizant machine – I’m saying this to explain that we haven’t done this, something that is obfuscated by the insistence that we call algorithmic applications “artificial intelligence.”

As an aside, the way we talk about these machines is largely the source of our confusion. We say that Alexa or Siri or similar devices are “talking” to us, but the most fluid and interesting things they produce are assembled by people in call centers from a list of pre-written responses: It’s just the Chinese Room argument with greater lag.

And perhaps, as Peter Watts suggests in Blindsight and Echopraxia (review forthcoming), there’s no real difference between us and a Chinese Room, but I think that most of us are unsatisfied with that answer, and it seems undecidable with the world as it is now.

I want to turn my attention here to the issue of ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, and similar applications. For those unaware, these are programs that can create strings of text and images that are often treated as valid reflections of human effort – writing and art.

Realizing that I need more information, I decided to open up ChatGPT and look at what kind of results it produces, it kicked out a message that it was at capacity, in the form of a “sonnet”:

Amidst the rush of curious minds,

The chatbot ChatGPT stands strong and true,

Withstanding the influx of requests,

Working hard to fulfill each one's due.

But alas, the server cannot cope,

And the error message rings loud and clear,

"Please check back soon," it gently hopes,

As it begs for a moment's reprieve, to reappear.

As the chatbot works to restore its might,

We wait in anticipation, with hopeful hearts,

For the chance to chat and learn, with delight,

And see what knowledge and wisdom it imparts.

So hold on tight, and wait for its return,

For ChatGPT will soon be back, and your patience will be well-earned.

Look, I’m still not done with How to Read a Poem, but this is a pretty dreadful poem. Sure, it’s got the most basic part – it’s a poem of fourteen lines, with a regular rhyme scheme. It looks like it attempted a Shakespearean sonnet (you can tell because it’s got four parts instead of two. These parts are supposed to have the rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG). I say attempted because it didn’t get the rhyme scheme quite correct (“minds” doesn’t rhyme with “requests”) and it scans strangely because the machine doesn’t know where stresses fall and doesn’t know what a syllable is.

Now, all that being said, it’s impressive that this tool is able to get this close without supervision – and that is what it is. It’s a tool. It isn’t making decisions, it’s predicting what the most likely next letter is. “Art AI” are similar – they’re predicting what an image should look like based on the prompt and the library of images they have on hand.

Look, if placing a urinal in a gallery can be artistic, then placing this terrible string of text on a landing page can be poetic.

The bolded letters “Write a sonnet about the status of ChatGPT.” appear above that poem – as if that’s the prompt it was given – and this is the result, which I fully expect is what it is: someone who had taken enough college English classes to know what a sonnet is got this response, said “yup, that looks like a poem” and put it on the landing page, and to a lot of people looks like a poem. But the most poetic act here was placing it in the context of the landing page. They took these words and put them in a particular context, as one might with black-out or cut-up poetry. However, you should not be fooled: this is not a poem. This is a lazy attempt at a poem: not by the machine, but by the person that entered the prompt.

All of these algorithmic tools are not AI, they’re labor saving devices, and the labor being saved is something that people actually enjoy: in a sense, in addition to being labor-saving tools, these are also leisure-saving tools. Why bother writing a story idea to put up on AO3 when you can just enter a prompt and get something like a comic by the end of the way?

With things like ChatGPT and Stable Diffusion, it will be much harder for writers and artists to make a living off of their work – which is just fine for the people putting it together.

Art and writing are, after all, expensive, and we’ve been taught to think that they should be cheap.

Explain to me, again, why the same software innovations that power these tools not used to put people in spreadsheet mills out of work? Why can’t they write a legal brief or a business plan or a press release?

Why are things that people enjoy doing being automated?

This, above is one of the moral arguments against them. There is also a practical argument against the use of Algorithmic tools for the generation of text and images: it represents a narrowing of horizons to rely upon them.

Labor-saving machines tend to be capital-intensive and labor-light. They cost more money up-front, but don’t cost as much money to run. Thus, long-term there is a tendency to replace labor with machines when the costs reach certain points. This is the nature of all automation within a capitalist system.

However, because these machines can only remix what already exists, producing variations on what has been done before, it stifles future innovation. Let’s say that ChatGPT somehow managed to produce a technically perfect screenplay – sonnets being notoriously unprofitable – and showed that this was repeatable. All of a sudden, we could expect to see all big budget films adopt this software.

The end result, however, would be that no really new movies could ever be produced, because the only new data being added to the library after a while would be its own products. Say hello to everything suddenly being the narrative equivalent of a room painted cosmic latte.

Here it is, the average color of the universe.

This would be cataclysmic for the arts, primarily, and the rest of culture, secondarily. Innovation requires variation, and you can’t simply crank up the noise in the generator to simulate this. You need real people working on the project and you need their own personal idiosyncrasies to show. Real art is made by people who have hangups and hidden talents and problems and perversity.

Even if there is a convincing use-case for these machines, I cannot help but feel that an over-reliance on them is a trap. Perhaps collaboration between a skilled artist and the machine would be better than anything produced by either on their own: but to develop those skills, the artist will need to practice and work and make mistakes and have problems away from the machine.

I realize that one of the most-repeated phrases on this website is “a thing is what it does” – but you cannot convince me that what these machines do and what an artist does are the same thing. It is, at best, an imperfect simulacrum and while it might be fascinating or aesthetically interesting, I maintain that human-produced art is always going to be better.

And I can state this without fear of it coming to bite me in the ass, because “better” is undefined and largely subjective.

※

As with most things, a conversation with my partner – whose latest round of book reviews went up last week – has shed some more light on the topic and, though I stand by what I said previously, I had more that I wanted to add that diverge a bit from the points I made.

The real allure and tragedy of the algorithmic tools that I am discussing in this piece – and which are a topic of discussion elsewhere – is that it allows everyone to live out a fantasy that they might not have all the time, but which regularly recurs in many people: the fantasy of being an artist.

Look, it seems significant to me that many great artists – whether their medium is visual, textual, musical, or otherwise – are the children of the wealthy. A vast number more of rather terrible artists are, too. Sure, we could dip into the so-called “nepo baby” discourse that’s been ongoing for a long time, but the nepotism in question isn’t really located at the point where the people discussing it are locating it: the nepotism is the same as with all artists who are the children of wealthy parents – they are the people who have the opportunity to be artists.

Now, it’s terrible and wrong that, in a very real sense, they’re the only people who have the chance to explore the arts in our contemporary era of hyper-extraction. However, I don’t blame these artists (well, not all of them, some of them are squandering their ability to do interesting things by being utterly boring, but that’s a conversation for another time), I actually find the existence of this block of people to be rather heartening: when given the space and resources, people choose to make art.

The problem is that we live in a world that doesn’t see the immediate benefit of this, because something that can’t generate more money in the next three months than it did in the last three months is thrown out and devalued.

If you don’t have the time and freedom to suck at something new, how will you ever get good at it? Especially with the utter fear that people have of appearing to suck at it? Why not get really good at writing prompts for an algorithmic tool that generates images or text? You can claim some measure of ownership over what it produces (though, of course, it’s not real ownership, and the algorithmic tool only exists because it stole information from a vast number of sources as training data).

Turns out the “AI” can’t do hands either.

But it’s a lot easier to master writing a prompt than it is to learn perspective, and how to shade, and how to draw hands or horses. It makes the fantasy feel somewhat achievable, even if it remains a fantasy: it’s something you can never really obtain, even if you can maybe hold it in your hand for a moment.

If arts education were properly funded, would we have this disagreement about “AI art?”

I mean, probably.

But it would be a different conversation, and there would be less investment on arguing for it. That’s all really the problem with it: I get it. I get the desire to make the images that you come up with visible to other people. I want that sort of thing too. However, I also know that I’d like to be a working author one day, and I know people trying to be working artists, and this sort of thing makes that inaccessible to them specifically by stealing their work and profiting off of it.

I’m not about to say that there’s no moral valence to the things that we build. Quite clearly, the construction of a tool – whether it’s an electric chair, a bioreactor to make insulin, or an SUV – has a moral dimension, and arguing otherwise is simplistic and thoughtless. There is a moral dimension to algorithmic artistic tools, but I also think that it might be possible to create a permissible way to use them: perhaps as a way to allow a budding young author to “co-write” with Shakespeare, Dickens, or Joyce, using it as a way to collaborate with a simulacrum of an author now long-dead, learning the things that these algorithmic tools might preserve (such as rhythm and word-choice), and then – importantly – putting the tools away after a time. Such a system would be an augment to the development of a writer, not a substitution for their own effort.

I would’ve killed for a chance to work with Roger Zelazny, personally, even if it would be much funnier to work with an AI simulacrum of Frank Herbert.

That, at least, seems like it would be fine to me, and the existence of such a permissible use-case means to me that there might be arguments for it.

However, it would be the involvement of a conscious mind that makes it “art,” in my opinion. Without choices being made, I don’t believe it would qualify.

※

I had no place for this one, and discovered it in the course of typesetting this article, but have an example of cursed British reflections on gender and sexuality, from the island that invented tablecloths to keep table legs from making men too horny to exist in polite society.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.