Edgar's Book Round-Up, September 2023

In the immortal words of a Tweet that lives rent-free in my brain, “Ah, September. The first of the final four months. The big boys,” et cetera. Unfortunately for me, it’s still been extremely warm in Kansas City, though that seems to be breaking now (but I’ll believe it when I feel it, or rather, when I cease being able to feel much in my fingers and toes due to the cold). Politically, the situation continues to be bad, but you can benefit some dear friends of the blog by contributing to this GoFundMe, which will support a space that looks incredible and where I personally want to spend my time and money. Links in this piece go to our Bookshop, as per.

※

First up this month was Nicholas Eames’ Kings of the Wyld in audiobook form. The first book in Eames’ Band series (recommended to me by my sister) introduces us to Clay Cooper, former member of a group of adventurers known as Saga, now a humble city guard, until Saga’s charismatic frontman – sorry, magic-sword-wielder – comes to beg Clay to help him get the band back together to rescue his daughter, trapped in a besieged city after she attempted to follow in her father’s adventurous footsteps. The conceit, if it weren’t abundantly clear, is that D&D-style adventuring groups are treated in their world much the same way rock bands are treated in ours. It’s to Eames’ credit that this doesn’t become tiresome, and in fact stays fun and funny throughout. More troubling is Eames’ continually referring to the innate prowess at violence of Saga’s sole Black member, which feels dangerously close to Tarantino-and-the-“N word” territory. Like, are we making references to, or are we repeating gross things from, you know? Ultimately, for me, Eames stayed on the right side of the line enough that I will probably be reading the sequels, and if anything, he puts rather more thought into justifying elements of his fantasy settings than others operating in similar territory.

My copy, purchased used from my local friends.

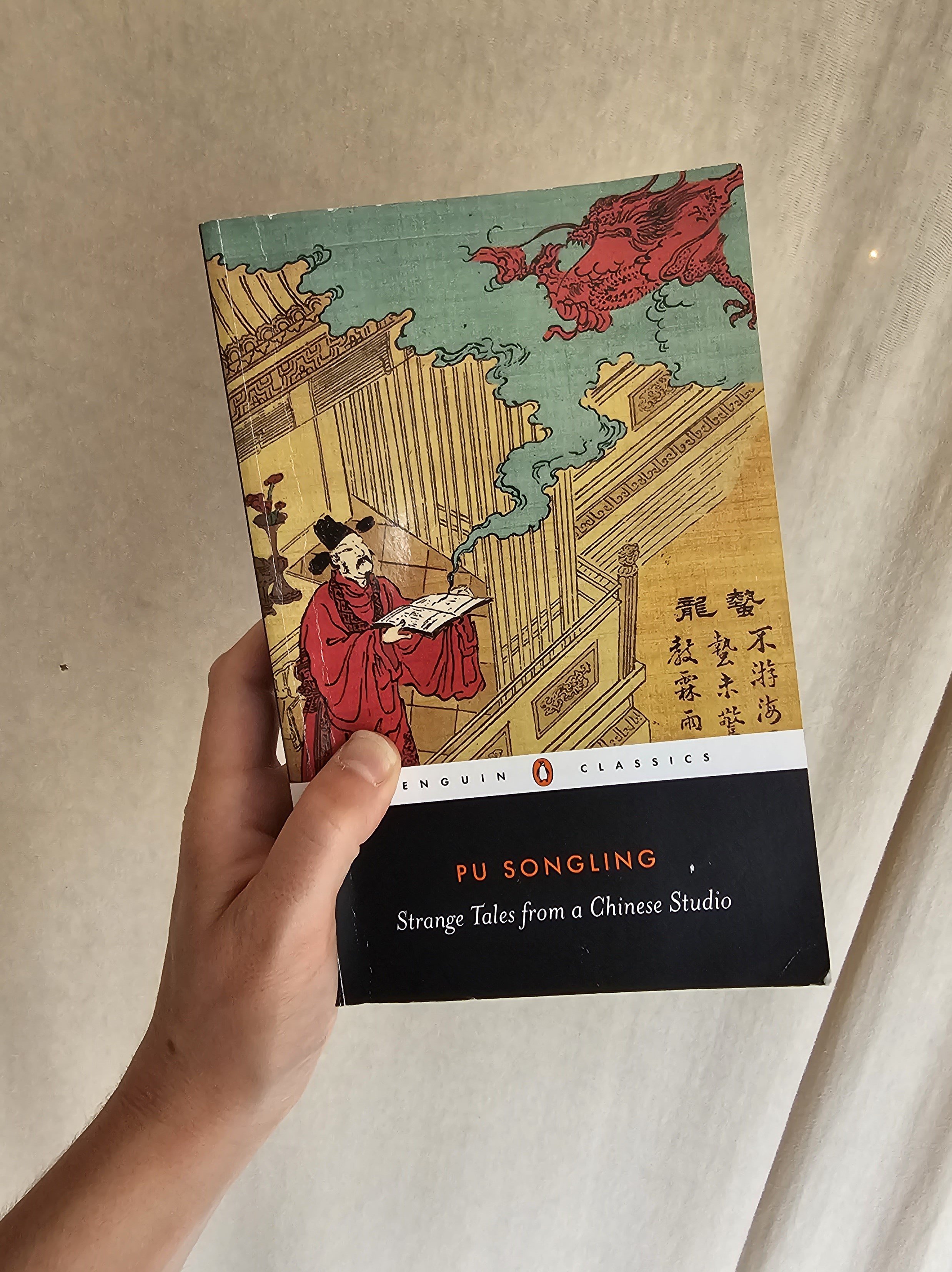

I next finished Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio by Pu Songling, selected and translated by John Minford. Drawn from the magnum opus that is Pu’s complete tales — which runs to something like eight volumes — the stories selected here seem to attempt to capture the breadth of the work by example, and, at least as far as I can tell, they do a pretty good job: ranging in length from one to 12 pages, the reader is treated to tales of trickery, transformation, and the supernatural. Sexual escapades, hallucinatory illusions, and plain old weird shit abounds, and it’s a delight. Minford, in his introductory material and the notes on the stories, does an admirable job of providing context where context is available; I wish there had been more indication of where the stories came from in the broader work, but it’s a version aimed at a popular readership, and as such, it succeeds. While I know very little about seventeenth and eighteenth century China, I am very interested in learning more, thanks to the joys of these Strange Tales.

I then proceeded to burn through a couple of recently-released novellas very quickly, the first of which was Cassandra Khaw’s The Salt Grows Heavy. Set in a war-torn nation that sort of feels like Russia, maybe, the novella is narrated by a man-eating mermaid as she journeys through a violent landscape, accompanied by a gender-neutral plague doctor. But to describe Khaw’s work by its plot is to do it an incredible disservice: Khaw’s language is where their work truly shines, and The Salt Grows Heavy is no exception. By turns spare – much sparer than some of their other work, which Cameron and I have both discussed elsewhere – and glisteningly viscous, the horrors the characters encounter are rendered in whatever way will make them the most unsettling. It’s delightful, and I burned through it in an afternoon.

The cover of Thornhedge, which is fine, I guess.

Next up was Thornhedge, the latest from Broken Hands favorite, T. Kingfisher – or rather, the most recently published. The back matter suggests that it was written and sold some time ago, and this comes through in Kingfisher’s new version of the tale of Sleeping Beauty. Told from the perspective of an ambiguously-immortal changeling as she by turns aids and attempts to prevent a Muslim knight from breaching Beauty’s tower, Kingfisher’s trademark charm and pacey qualities are here muted, in favor of a rich melancholy and an attitude of dismay at how things have turned out. While it’s quite different from what I’d expected, and certainly sits closer to Nettle and Bone and her versions of classic Weird Fiction, it was nonetheless a swift and pleasant read.

After that we have, in audiobook form, Charles Stross’ Glasshouse, which Cameron discussed here. In this more-or-less standalone novel, Stross gives us Robin, who is living it up in the fully automated luxury space communism that has grown from a horrific war – in which Robin participated, and of which most have excised their memories. But when it starts looking like someone wants Robin dead, he flees into what is billed to him as an anthropological-historical study, the participants of which will live the way they did in “the dark ages,” i.e. the mid-late twentieth century. Furthermore, their “starting points” in the study will be randomized, so Robin’s a girl now. Honestly, Stross’s send-up of “normal life” in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries is hilarious, though I’ll admit, Robin’s frustration with and confusion at the demands of femininity in the period were relatable to the point of painful hilarity to me as a transmasculine person from the same era. The ending felt a little rushed, but overall, it was very enjoyable, and while elements of it felt dated, I frankly didn’t expect such a sensitive handling of issues of gender and sexuality from Stross.

The cover of The Darwin Affair, which I rather like.

I followed that with another audiobook: Tim Mason’s The Darwin Affair. The novel finds its center in Chief Detective Inspector Charles Field, the real-life model for Charles Dickens’ Inspector Bucket, here tasked with discovering the truth behind what seems, at first blush, to be an attempt on the life of Queen Victoria. But the plot thickens – as it must – and Field must contend with the luminaries of the scientific world as much as he does the scrabbling poor of Victorian England. While I’m not sure I would have picked this one up had my mother not recommended it to me, I ended up enjoying it quite a bit: looking past the copaganda – albeit with a little difficulty – Mason has structured the story extremely well, and clearly revels in the grotesquerie of the period, both in its social inequities and its gruesome facts. I enjoyed it enough that I may seek out the sequel, and if you’re down for a period detective story, you could certainly do worse.

Next up was another library acquisition: Boys in the Valley by Philip Fracassi. Blurbed by such luminaries as Stephen Graham Jones and enjoyed by my friend and favorite Bookstagrammer, I had high hopes, and was deliciously not disappointed. When, on a winter’s night in 1905, the local sheriff brings badly-injured man to St. Vincent’s Orphanage for Boys in the hills and hollers of rural Pennsylvania, no one anticipates the literal hell that breaks loose – but break loose it does, and now the boys must choose sides in a battle between the forces of hell and all the holiness of the Catholic church. Fracassi handles a large cast well, and the novel zips right along: the only reason it took me more than a couple days to finish it was because I had to work, and it was a rough weekend. But – and I’m going to I guess spoil a little here, maybe, vaguely – I thought it was a very bold choice on Fracassi’s part to position Catholicism as being synonymous with goodness, especially in a story set in a boy’s orphanage, especially in a story written now. Which is not to say that every Catholic character is a paragon; far from it. Certainly a bold choice, but to his credit, Fracassi commits to his bit. It was, ultimately, good in the sense of enjoyable, and good on the level of its prose, which was quite tight without being overly spare. I’ll be seeking out more of Fracassi’s work, for sure.

The Spirit Bares Its Teeth also brought back Evangeline Gallagher for the cover, which was an excellent choice.

I packed The Spirit Bares Its Teeth by Andrew Joseph White when Cameron and I left town for the weekend to go to a wedding, and brought along another book, thinking that I surely wouldn’t get to it. But what actually happened was that, over the course of sixish hours in transit, I swallowed Spirit whole. We follow Silas, a young trans man with the misfortune to have the violet eyes that signify extrasensory powers in an alternate version of the 1880s in which the veil between the living and the dead has grown very thin indeed. Doomed to be married off, after a grievous social misstep, Silas is shipped off to a sort of finishing school for wayward girls with violet eyes, where all is most certainly not as it seems. Longtime readers may recall how much I enjoyed White’s Hell Followed With Us, and I certainly enjoyed The Spirit Bares Its Teeth: White’s characters shine, his prose is both pacey and delightfully gross, and his character relationships are fraught and tender in unexpected and well-observed ways. My issue with The Spirit Bears Its Teeth was, frankly, one of language: goofy as it is, so many things were “fucked up” or “going to be okay” that I struggled to buy it as a story taking place in late nineteenth century England when the characters placated and validated each other using such distinctly American turns of phrase. More than any other element – including characters’ transness, which felt organic and valuable in a way I really enjoyed – it made the setting feel like set dressing more than a specific place and time. But, again, I still enjoyed the fuck out of it, and I’m already awaiting White’s next outing with great anticipation.

We close this round-up with another item from that same library trip, and the continuation of a series discussed previously: The Mystery at Dunvegan Castle by T. L. Huchu, the third installment in his Edinburgh Nights series. Our beloved heroine, Ropa Moya, has been dragged along to a major magical conference in her role as an intern for the head honcho of Scottish wizardry. As egos, traditions, and blood feuds clash, Ropa will have to determine who stole an incredibly valuable work of Ethiopian magic, brought to the isle as a loan, and taken almost as soon as it was unveiled. This is not a standalone story, and definitely depends on characters and elements introduced in prior novels; it is to Huchu’s credit that, despite not having gone back to read the earlier entries in the series, I was able to recall the elements that reappeared here with clarity. Ropa’s narrative voice, too, is completely charming, her changing attitude towards her own powers and traditions well-rendered. In an unusual feat, she genuinely feels like a fifteen-year-old, with all the self-assurance and conviction that entails. These books are a continual delight, and I am already hoping for more.

※

That’s all for now, friends. We’re on Tumblr and Cameron and I still maintain accounts on the social media platform formerly known as Twitter.