Kill The Cop On Your Bookshelf: Recommendations for Unbureaucratic Fiction

Which is not to say there’s no place for anti-bureaucratic fiction, where one throws themselves on the workings of a machine to make it stop,

(Note: The reference here is to William S. Burroughs’s admonition to “kill the cop in your head".)

Edgar and I are traveling, and so we’ve prepared these posts in advance. Right now, I want to share with you something that isn’t quite a genre – it lacks the coherent myth-structure of the Woman-In-House novels that I spoke about previously – but which are unified by a particular set of qualities. I don’t have a good name for them, so I’m going to describe this as “unbureaucratic” fiction.

I purposefully went for “unbureaucratic” rather than the more easily-parsed “anti-bureaucratic” because these are not novels about Reaganite/Thatcherite supermen smashing bureaucracy. Instead, they are simply adventure novels where the central characters are specifically not part of a larger organization. This is one of the qualities that I tend to look for most fervently in new reads. As much as I might enjoy The Laundry Files, that is not wholly because the main character is a civil servant – though, admittedly, I like Stross’s handling of that more than most — I feel it’s often (pardon the pun) an unnecessary cop-out.

What I am talking about is a lazy trend that I see in genre fiction spaces: the author wants to write a novel about a particular set of problems, and the solution is to create a fictitious organization tasked with policing that kind of problem. I call this “lazy” because it obviates a number of questions that I personally find interesting, but which are somewhat high-effort to solve: notably, what motivates the characters to attack this problem? Where do they get the information that they use to attack this problem? Why do the characters spend time together.

Have you noticed, for example, that in all of these stories, almost all of the characters only socialize with their coworkers? In an attempt to solve a set of thorny and potentially difficult questions, a number of fantasy writers have created multiple worlds populated primarily by different kinds of cop that only spend time with other cops of the same variety. All of these characters seem to live in segmented wizard-cop-ethnostates, and that’s weird. I find it unpleasant. So when I run to the opposite end of the spectrum, what do I find?

In some cases, I find examples of Woman-in-House fiction. I’ve read so much of it principally because it fits the bill for unbureaucratic fiction. What else is there, though?

The term used to describe this kind of fiction in the TTRPG space, generally to describe the new game Public Access is “adults on bikes” – formulated in response to the common “kids on bikes” description of popular stories like Stranger Things. If that’s what we end up calling it, then yeah, sure. I’m not going to lead the charge on making that list, though.

Note: Spoilers ahead.

※

It by Stephen King

(Review forthcoming, but...c’mon. It’s It.)

This one, despite appearances, is an edge case. While the characters are not part of a formal organization, they are picked by destiny to fulfill a particular role. I am including it here to discuss this.

Oftentimes, bureaucratic fiction is an alternative to the “chosen one” model, though they also often overlap. When it comes to the chosen one trope, I happen to think the Loser’s Club is a wonderful example of how to do it right – it doesn’t make them act, necessarily, not on big issues, but it does grease the wheels in a particular direction. The characters all have their own motivations and their own reasons for doing what they do, but fate tugs at them in a way that is unsettling and eerie.

I will have more thoughts on this in my next book roundup, but you’ll have to wait until then.

Lovecraft Country and Destroyer of Worlds by Matt Ruff.

(First reviewed here, second reviewed here.)

Lovecraft Country, which I’m going to use to refer to the whole series of books, is about a small community of black people living in Chicago in the 1950s who are in the sights of a cult that taps into strange and unknowable powers. It takes the track of inverting the normal racial dynamics of Lovecraft’s fiction and having the white supremacist authorities serve dark powers – something also done in P. Djèlí Clark’s excellent Ring Shout, which I loved but which doesn’t meet the criteria for this list.

The character motivations are perfectly drawn: they all want things and enjoy things, and are drawn into a demimonde of cults and wizards through no fault of their own. They are reactive, but this does not make them weak: they simply want to live their lives and come to understand that dark wizards are a thing that they’re going to have to deal with from now on.

The glimpses of relatively mundane life that are visible at the start of each story and in little islands spread throughout it are excellent additions: while I love blood and monsters and magic as much as the next degenerate gremlin, the contrast between normality and extra-normality really sells this kind of story. In addition, Ruff has clearly done his research, and clearly rooted his perspective in the lived experiences of people who lived under Jim Crow. I can only imagine the amount of background work that he did to make sure that everything fit without warping the source material.

Last Exit by Max Gladstone

This is the big one – my current early front-runner for my book of the year (who cares if it wasn’t released this year; I read it this year.) This story follows a group of people who discover something very much like magic and decide to set out to fix the world – it goes poorly, and they have to reunite ten years later to finish what they started.

All of the characters are motivated by a desire to do good, but there is a texture to their motivations. They are not all in agreement about what good looks like, and conflict emerges among them in reference to how to achieve what shared goals they have.

It is an absolute banger of a novel, in my opinion, and is essential to my formulation of what I’m calling, here, unbureaucratic fiction. It was in reading this novel, and seeing how all of the characters are drawn along and motivated – and how their motivations change over time! – that allowed me to see just how the dominant, bureaucratic, mode of adventure story is being constructed. None of these characters is a “chosen one”, and none of them is ordered to go on this quest. The end result is a deeply moving story about good intentions and how – even battered and broken – they are worthwhile.

The Blade Between by Sam J. Miller

Okay, so admittedly, one of the characters here is literally a cop, but that doesn’t play a major role in his motivation. This is a story about people in a small town trying to resist gentrification. The main character, Ronan, is a burnout and a famous photographer, and is drawn into a supernatural battle that manifests in our world as the conflict between gentrifiers and the natives of a small town in New York state called Hudson.

It isn’t exactly made clear the absolute scope of this battle, only that it is happening and there are clear sides in the conflict. It may be highly localized, it may be one front in a conflict between competing principles, but for the characters it doesn’t really matter all that much. What does matter is trying to come to some kind of conclusion that satisfied the parties involved.

I did like that this book was not dichotomous in nature. The end goal was not the annihilation of the other side of the conflict but a level of compromise being achieved – a dialectical synthesis between the opposing parties. This was not, it should be noted, a bloodless process in the story. One of the three central characters ends up as a ghost by the end of it – but even that is a satisfying conclusion: the dead in Miller’s novel are not the psychospiritual equivalent of William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops, decaying repetitions of a static original, they’re much closer to Billy Pilgrim from Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.’s science fiction masterpiece Slaughterhouse Five, unstuck in time and moving freely between different points, which is a fascinating concept.

The Night Will Find Us by Matthew Lyons.

(Reviewed here.)

Six teenagers enter the woods, and only one emerges at the end of a too-long time, traumatized and bloody. The story, as a whole, happens between these two events. This is a fairly common setup for a horror story: whether we’re talking about Friday the 13th, Evil Dead, or any number of other low-budget films that set us up to hate a group of adolescents and then cheer as they get brutally eviscerated, we all know how it goes. Our setting here is the Pine Barrens in New Jersey, an unexpected wilderness of a million acres set in one of the most built-up states in the US.

But Lyons diverges from the plan and takes us in an unexpected direction. One of the most unpleasant of the teenagers – foulmouthed Nate, whose primary hobby appears to be blowing things up and making jokes at his friend’s expense – does die fairly early on: he’s shot by Parker, one of the other characters, fairly quickly, which is the first moment of real terror and confusion. Parker, immediately after, flees the group, going off to pursue his absent father who disappeared into this area of the pine barrens months and months beforehand. After this, the narrative is split pretty evenly between Parker and his cousin, Chloe, who is a somewhat more generic character.

Things are handled fairly realistically for a brief period, and then the supernatural experiences begin to enter into it. What looks, at first, like a fairly typical slasher setup graduates at the end to a Cosmic Horror story with notes of real tragedy. This is not a novel that kills its characters lightly, but there is quite the body count in these pages.

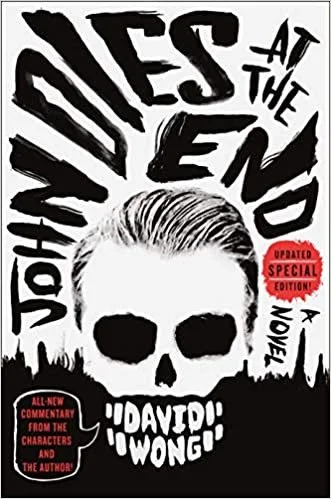

John Dies at the End by Jason Pargin

(Reviewed here.)

Originally published serially on the website Cracked, Jason Pargin’s web-novel-turned-dead-tree-novel is a strange beast, as should be expected from him. It follows two characters, John and Dave, who have an extremely bad night with an unidentified drug they refer to as “soy sauce”. The drug apparently disables some kind of faculty that all people have that suppresses certain information from coming in: the end result is that they have almost total awareness of their surroundings, verging on precognition, and can see and interact with supernatural forces.

They are motivated by the sinking realization that they are the only people who can interact with what they see and hear. Dave, at least, wants to live a normal life, but is burdened with the knowledge that the world will fall to pieces. Part of their new awareness is the understanding that the past is changing, and if they don’t act, the world around them will become an unrecognizable hellscape.

Generally speaking, I’m not a major fan of horror comedy, but Pargin actually manages to make this story both funny (at least, I found it extremely funny when I was in high school and still have a soft spot for it after all this time) and uncomfortable. The best example of this, from the first third of the book, is a possessed individual who looks and acts almost exactly like Fred Durst of the band Limp Bizkit and insists that the other characters refer to him as “Shitload. Know why? It’s because there’s a shitload of us in here.” – and when he dies, a swarm of creatures that look like toothbrush bristles fill the air around him and begin to drill into the flesh of everyone around them, digging in with intent to possess.

Oftentimes, horror is just comedy without the punchline. John Dies at the End proves that you can have both horror and a punchline.

No Gods, No Monsters by Cadwell Turnbull

While not exactly a horror story, No Gods, No Monsters rests on a horrific premise rooted – in part – in reality. A werewolf is caught on video, and all of a sudden the world is confronted with the knowledge that monsters – actual, straight-from-the-movies monsters – are real. Does anything really change?

Not really.

The horror of No Gods, No Monsters isn’t that everything will change. The horror is that nothing will change, even as the scales fall from our eyes. The characters struggle with the emerging knowledge that monsters – and magic – are real. Some of them are monsters, and struggle with coming out of the closet. Some of them are not, and struggle with their fear.

One thing I appreciated about this story is that it is written from an anarchist point of view. Major characters are actually involved in running an employee-owned anarchist bookstore, and they bring the techniques used in that lifestyle to addressing the problem. They discuss, endlessly, they build consensus, they attempt to reach rapprochement.

It’s the first in a series, so it doesn’t end conclusively, but I intend to read the next one when it comes out.

The Hollow Places by T. Kingfisher

I wanted to review this one in the last batch, but it didn’t fit as well as The Twisted Ones. This was my introduction to Kingfisher’s work, and I absolutely adored it (if Last Exit is my favorite-thus-far for 2023, this was my absolute favorite I read in 2021. Still mulling over 2022.)

Kara has recently divorced her husband, and goes to stay with her uncle and look after him instead of returning to her childhood home. While there, she finds a strange portal that leads into another world. However, this is far from Narnia. The world on the other side is a swampy mess filled with the detritus of dozens of other worlds and monsters – both formerly human and otherwise – that can be found there.

This is another story, like most of the Woman-in-House novels and John Dies at the End above where it is necessity that motivates the heroism on the part of an everyday person: they are directly threatened or precisely empowered to deal with the exact problem that has arisen, and they have to just get to it, or else something terrible happens.

I loved Kara as a character, and her entire situation: I would recommend that you pick it up if you can find a copy (hint: the link goes to Bookshop.org: you can get one right there.)

Vurt by Jeff Noon

(Reviewed here.)

The question lingers: is Vurt cyberpunk or something else? There are apparently robots in it – but there are also ghosts and talking dogs and drugs that come in the form of feathers. It follows a feather-junkie named Scribble and his band of friends as they seek to commit petty crimes and get high.

Of course, this isn’t Scribble’s mission: he’s looking for a particular feather. Curious Yellow is a high-level, pure-yellow Vurt that lures the user in and then traps them in a manifestation of their worst fears. Scribble took it once before, with his sister (and incestuous partner) Desdemona. Scribble managed to escape, but Desdemona was not simply mentally trapped, she was physically swapped with a strange creature from the Vurt that Scribble and his friends took to calling “the Thing from Outer Space”, a boneless, six-limbed “living drug” that the Vurt decided was of equal value to Desdemona.

Now Scribble and his friends lug the thing around and occasionally scrape its excreta for a quick high as they seek to find another copy of Curious Yellow, so that Scribble might someday exchange the Thing for his sister. However, it’s been five years, and there’s still no sign of the pure-yellow feather.

It is, quite obviously, one weird as hell book. It’s trite to call prose hypnotic, but Noon’s prose actually feels dissociated as a result of his use of surrealist techniques (notably a pattern of cutting-up-and-rewriting his stories in a process he calls “dub fiction”, in reference to dub music.) It’s also far from the most pleasant book, though I have a deep love for it: there appears to be a deep and intentional attention paid to the setting – the real-world city of Manchester, in the UK – that I could halfway expect to almost perfectly match the city as described in the book, right down to the foul odor. It feels like the novel captures someplace, but it’s impossible to say where. I am left with mere speculation on that matter.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.