Mapping N-Dimensional Gender Space: Crafting a Healthy Masculinity, part ???

Being a cisgender person married to a person currently going through a gender odyssey makes you aware of gender in a way that you tend not to be without a lot of introspection and study. I say this not simply because my partner is recovering from surgery and – consequently – is forced into the depression-LARP of recovery at the same time that I’m on furlough from teaching for the winter break, which has led to a number of conversations about that odyssey.

Don’t worry, though, I’m not going to be doing my version of Maggie Nelson’s the Argonauts anytime soon – the classics reference is, in this case, simply the metaphor closest to the top of the pile – but I am in a reflective mood, possibly something that the recently arrived New Year contributes to.

I am also preparing for a new semester of teaching research writing, something that leads me to think back upon prior years’ student research projects. Part of why I like teaching research writing is that I tend to leave the door open for students to pursue topics of their own choice and – as such – I tend to learn a lot about a wide variety of eclectic subjects. There was, in one of my classes, a recent constellation of gender-related papers, and I’ve been worrying at some of those subjects as a dog might worry at a shoe.

The most consequential of these thoughts comes from a student paper on muscle dysmorphia – what is sometimes colloquially called “bigorexia”. This condition, which is often thought of as the spear counterpart to anorexia, is characterized by the person showing the maladaptation engaging in constant exercise, to the point of being self-destructive. The folk diagnosis is that these young men cannot process objective reality and view themselves as puny weaklings, and so engage in these fitness routines in the hope of getting the “gains” that they so desperately want.

However, as far as I can tell – and perhaps my own research has been somewhat limited – it seems to me to be a cisgender version of gender dysphoria, a condition that a large number of transgender people show where the traits of their body that lead to them being gendered inappropriately become objects of fixation as they attempt to correct it. This is a spectrum that has a pathological and a non-pathological end.

This can look uncomfortably like the sort of autophrenology that you see in incel circles – where people obsess over fractions of a millimeter of jawbone and that obsession turns poisonous. I want to make clear, though, that I am not saying that transgender people or those with muscle dysmorphia are incels, nor am I saying that those with muscle dysmorphia or incels are transgender. None of these groups is a supercategory to the other ones, but the repeating theme of gender-based feelings of unhappiness, inadequacy, or frustration is an interesting correspondence that might point to a higher-order correspondence that isn’t really being examined closely.

The juxtaposition implicit in the “Barbenheimer” meme might, itself, be a comment on this: Oppenheimer cannot be apolitical (I feel it was, actually, a deeply conservative film) by putting the two next to each other a synthesis can emerge.

Another factor feeding into this is the article “Woman in Retrograde” from The Cut, written by Isabel Cristo. The article, while interesting, feels like more of the introductory portion of a longer piece than a completed thought. I became aware of it while riding in the car and listening to NPR, where Cristo gave a rough summation of her thoughts – 2023 was the “year of the girl” to hear her tell it, with its obsession with “girl dinner” and “girl math” and the pre-adolescent imaginary evoked by the Barbie movie (which, I’ll admit, my fever-dream “Theses on Barbenheimer” post is quite positive on). This is also something that came up in my class: two young women wrote papers on gender for my class: one of them brought statistics and one of them brought Barbie and Taylor Swift, and they both arrived at opposite conclusions, which ended up being a point of contention during the end-of-semester presentations.

What Cristo discussed was the infantilization of women over the course of this past year. There was a certain regression in culture, with women being replaced by “the girls,” in a sort of retreat to a pre-adolescent, pre-political imaginary. Cristo rightly calls out a particular bit of the Barbie movie as emblematic of this:

When she’s confronted by a crabby Zoomer who calls her a fascist, Barbie sobs that she couldn’t possibly be one because she doesn’t “control the railways or the flow of commerce.” The joke here is the absurdity of bringing politics into this context, where we all know it doesn’t actually belong.

The upshot here is that retreating from womanhood to girlhood is largely a flinch away from the political. I’m not completely convinced of this, but it does seem to be a shift in gender expression, and it could have larger implications.

What this gestures at is something that not many people tend to understand: while we may have roughly congruent ideas about masculinity and femininity, it turns out that “boy” is a different gender from “man” and “girl” is a different gender from “woman” – similar to how, according to my sister-in-law, one of the Talmudic genders is just “elder” (regardless of what gender the person in question was previously). This suggests that people progress through several gender identities over the course of their life. What is “cisgender” is simply the socially-approved trajectory through possible gender identities.

Given the tightly-constructed nature of gender identities in American culture, this is an important thing to understand: how one acts like a “man” is different at eighteen from how it is at thirty-six and at fifty-four. There are transformations and translations to the identity that are socially mandated, and someone at thirty-six behaving like an eighteen-year-old is socially censured, though someone at fifty-four behaving like a thirty-six-year-old is censured to a lesser degree: these two “stations” in the gender trajectory are considerably closer to one another, despite being separated by the same degree of time (it could be a percentage-of-life issue, I suppose, but someone at twenty-seven is expected to be more like the thirty-six-year-old than the eighteen-year-old).

You know…gender.

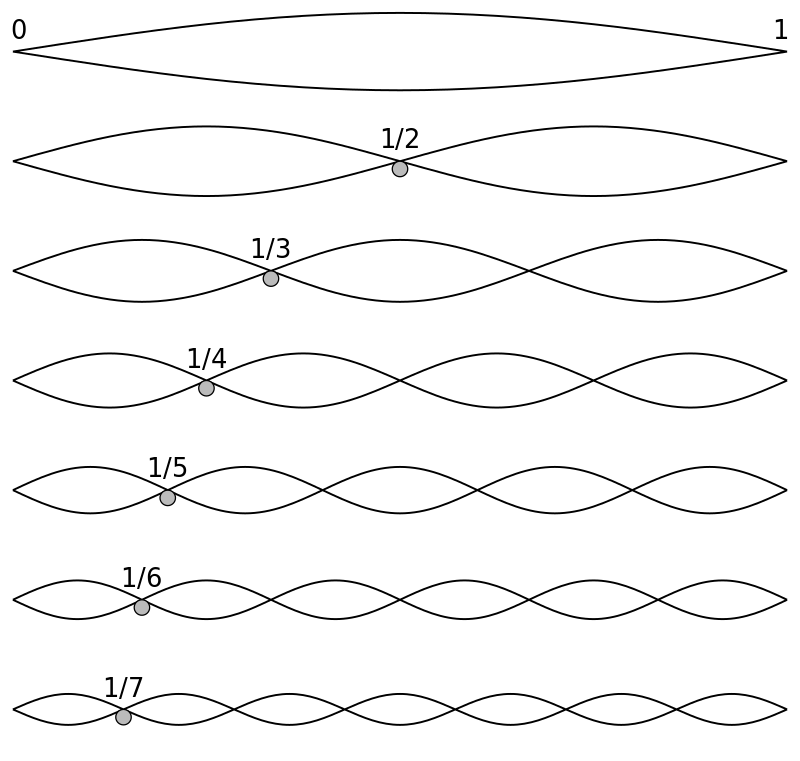

I’ve already used the term “trajectory,” so let me explain that a bit. If we consider every possible expression of gender identity as a point in an N-dimensional volume, with similar expressions adjacent to one another, and the most extreme divergences at the edge, what you would see is two vague clouds – masculinity and femininity – and a large swath of territory that is neither (while most people are statistically masculine or feminine, I’m reasonably certain that, in probabilistic terms, the number of potential non-binary identities is vastly greater).

Because of personal experience, I’m going to focus on the masculine portion of the volume. In this you have every potential expression of masculinity, from Marcus Aurelius to Saint Francis of Assisi to Ragnar Lothbrok to Oscar Wilde to Beau Brummell to Doctor James Barry to the guy down at the gas station who just doesn’t really give it any thought. It also contains all fictitious individuals that portray masculinity – Conan the Barbarian and Tom Joad and Frodo Baggins and Colonel Gentleman from The Venture Brothers, et cetera, et cetera. Needless to say there is a great deal contained in this space – to the point where, frankly, it seems like a set of empty signifiers. But if we put a hold on the whole unmarked default thing we get somewhere more interesting.

Despite the fact that I’m listing off individuals, what I’m really pointing to are specific images of people crystallized in popular culture. Marcus Aurelius was not always the Marcus Aurelius that is remembered by history and popular imaginings. The historical figures, considered this way, are no more real than the most crudely drawn stock character: real people are complex and contain multitudes. Characters – even the most three-dimensional, deep characters – are often the opposite.

But before we get into arguing about the quality of the shadows upon the cave wall, let’s proceed with the first issue.

…see? Gender.

If we accept that each of these individuals, real and fictitious, is representative of certain well-documented points in the volume of masculine Gender-Space, what we also need to understand is that real people are characterized not as points but as trajectories. They change over time, and the way that a male human being acts at ten is different from how he acts at twenty and at forty and at eighty. Each of these may be a “station” upon the journey, a point in the trajectory, but they do not constitute a whole, permanent, and substantive identity. The real identity is the trajectory, the process of living that we go through.

So let’s return to those individuals who show body dysmorphia and gender dysphoria. What is happening here is that these individuals have an idea of their “gender trajectory” that is different from their actual trajectory. Note, however, what I am referring to here is not “““biological sex””” or whatever – what I’m saying is that ones trajectory through gender space is not wholly under their control: it, like many things, partakes in a certain amount of social construction, but it is a negotiation between a minimum of three parties – the person’s conscious self, their unconscious self, and the Big Other of the society in which they live. Much like a body moving through interplanetary space, these three metaphorical bodies exert a gravitational pull that tug on the trajectory, pulling it one way or another.

At times, this may cause someone to slingshot out of the volume of one binary gender, or off into the strange outer reaches of unexplored non-binary gender expression. At others it may lead to a rapid oscillation between points in binary gender expression, straddling the line between masculinity and femininity.

I don’t understand abstract mathematics at all, but it seems an apt metaphor.

What this also suggests, though, and what I want to express, is that this means that even a purely cisgender experience of the trajectory can be just as complicated, it’s simply that it’s stamped with broader social approval. Because it receives approval, it’s often less examined, and so it appears to be simpler. Consider, though: how many people who have a complicated relationship to their own masculinity or femininity, but have even less of a connection to the “other” gender and don’t feel themselves to be strictly non-binary might really be gender-fluid, just with both genders being different kinds of man or woman?

If one has a complicated experience of gender, but is not strictly transgender or non-binary, perhaps there is a tendency to attempt to double down? To intensify their gender presentation by seizing upon a particular signifier of that gender identity and expanding that to be a whole or near-whole of who they are?

How many men with muscle dysmorphia are led to harm themselves with excessive exercise because their masculinity is not allowed to be complicated? How many men have died of overwork because they think of themselves as providers for their family? How many women develop eating disorders or stay in destructive marriages or give birth because they thought that being more feminine would make them more fulfilled?

To bring in an element of ludo-analysis, this might also explain a bit of the hostility that people who fall outside of cisgender identities experience: they are Huizinga’s spoil-sport, breaking the magic circle around each gender identity and thus calling into question the validity of the game. What the conservative ideologues don’t understand is that the game of gender identity is not a machine for producing nuclear families – where the reward for playing the game well is a more attractive partner of the “opposite” sex (which, when you get down to it, is the problem of the incel in a nutshell). It’s a personal journey of becoming, a trajectory through uncharted space toward an imagined destination.

Of course, there’s no problem with being a spoilsport when the other party is trying to make you play a stupid game.

This, I believe, is a theme I’m going to have to return to. For the moment, though, I think that this is a good spot to put a pin in the piece and take the time to think through next steps.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.