Cameron's Book Round-Up, Starting 2024 (Reread-a-Palooza, part 1)

As always, before continuing, we would recommend that you think about giving something to help with the ongoing attempted genocide in Palestine and elsewhere in the world. Our recommendation is something like Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières or eSims for Gaza, though, as always, follow your conscience. It often feels like there’s not much we can do here, but it’s still important to keep it in mind: we can’t allow ourselves to forget what it happening in Palestine, in the Congo, or elsewhere in the world

※

This is something that’s been percolating for a bit: the piece I wrote on criticism a while back, which is different from the one I wrote on the hate-consumption of media (something I am compelled to clarify every time it comes up because of how the word “critique” has pejorated in the American vernacular), included a discussion of how re-experiencing something lends new insights into it. I began to wonder what I might have missed in a number of my favorite books — from both the time I’ve been writing reviews and from before.

I decided to jump back in to them. This proved to be a weirdly controversial move. At least one friend whose opinion I respect told me that he never rereads anything: there are simply too many books to work through, how can anyone waste time backtracking? And I’ll admit, to a certain extent that makes sense. None of us will ever read the whole corpus of the English language, why intentionally limit yourself? Why narrow your horizons in such a way?

Of course, it could be that rereading is a fundamentally different act from the initial reading. By returning to a text with a memory of it, you can discover parts of it that you failed to see on initial — or second, or third — readings. I hesitate to suggest that you “decode” texts when you read them, or something to that effect, but it is my belief that the act of reading is a collaboration between the reader and text, and so the results will be fundamentally different if you are fundamentally different. You can never really “read the same book again” because much like Heraclitus’s river-crosser, you’re not the same person.

※

The Hollow Places by T. Kingfisher.

(First reviewed here, reviewed by Edgar here.)

One of the earlier horror books I reviewed for this website, and still one of my favorites. Kingfisher — a pen name used by Ursula Vernon — has written a number of novels for younger audiences and a handful of more traditional fantasy novels. This was her followup to The Twisted Ones (reviewed here by me and here by Edgar) and is a fix-up or pastiche of Algernon Blackwood’s The Willows (sigh…reviewed here as part of a collection. I’m going to be putting a lot of links in these re-reviews, aren’t I?) in the same way that earlier book was a fix-up of The White People (which…I haven’t read. I probably should at some point.) Of Kingfisher’s trilogy of works that fall into a Post-Feminist Gothic — what I tend to call “Woman-in-house” books — I think this one still hits the best, and I would still recommend it without reservation.

Kingfisher writes excellently about adults just shy of middle age, using the same skills that enable her to write compelling YA fiction. There’s something both surreal and satisfying about this transposition of style or trope onto a different kind of protagonist. It remains light and engaging even when the contents of the story are anything but.

Having now read Blackwood’s original — and, inexpertly, having used it to teach the beginnings of literary criticism to a college classroom — gave me a new appreciation for some aspects of the novel. The recurrent use of otters as a motif, for example, or her handling of the strange noise that plagues the original story’s narrator and his Swedish traveling companion (cleverly called, just “the Swede”.)

The plot is fairly simple, with most of the joy of the story coming in on a stylistic and character level. Kara, a woman in her 30s moves in with her Uncle Earl, the proprietor of the Glory to God Museum of Natural Wonders, Curiosities and Taxidermy after her marriage falls apart — imagine the Mystery Shack from Gravity Falls, but it’s played earnestly and located in Hog Chapel, North Carolina instead of the Pacific Northwest — and begins to help him run the place as his knees begin to give out. After he has to go in for surgery to deal with them, she discovers an impossible hole on the second floor of the building, leading out a concrete hallway in what should be empty space. She proceeds to explore it with the help of her friend, Simon, who mans the espresso machine at the Black Hen Coffee shop next door. They discover horrors they aren’t prepared for on the other side of it.

Season of Skulls (the Laundry Files, #12) by Charles Stross.

The one new book on this list, brought about by a hold on Libby coming due. Stross continues to be a wonder: a mashup of Regency Romance, spy fiction, Lovecraftian horror, gothic fiction, The Boys from Brazil, and British popular psychedelia in the vein of the Prisoner.

Stross somehow manages to alchemize all of these into a pastiche of such complexity that it approaches something new. This is the third of the “New Management” trilogy, in which the ancient horrors have returned and turned the modern world into a dystopian hell, complete with public executions and (even more) for-profit policing.

While the hell depicted isn’t quite as chilling as something less pulpy — Claire North’s 84K comes to mind — the admixture of pulp allows for some rather amusing variations on the theme. While I much prefer the simpler, original flavor of the Laundry Files found in The Atrocity Arvchives and the earlier entries in the series, I think that I’ll probably leap to read the next entry, nonetheless.

The Filth by Grant Morrison.

(Link goes to Bookfinder — it isn’t available on Bookshop.org)

And so we enter a peculiarly Scottish stretch — or continue it, more properly, as Stross is Scottish — with a foray into several of Grant Morrison’s standalone works. The Filth was actually my first exposure to Morrison, whose Doom Patrol run Edgar and I are so keen on: I first read it while in high school, and my last trip through was in graduate school, about six years after. Now, I look back on it from the first month of 2024 and can’t help but feel that it is a much more incomplete and disconnected work than it first seemed.

The Filth moves by dream logic. Each panel is rather coherent, but when you expand it outward, the story-lines are fractured, limping things, reflecting the brokenness and alienation of the characters in a kind of internal disconnection. There is still a unity to it, but it is a unity that centers around an absent logic, the way a doughnut centers around an absent center.

It is a psychedelic superspy comic (and here I note that I should also make the time to re-read Matt Fraction’s Casanova, which I’m not sure is necessarily in conversation with this one, but which I greatly enjoyed and which can be described similarly), centered around a man named Greg Feely who is assumed to be a pedophile by his neighbors and who has only his cat to give him comfort. Except that sometimes people in day-glo bondagewear show up and insist that Greg is actually Ned Slade, top negotiator for the Filth, an organization that is often described as the garbagemen of reality and are tasked with cleaning up rogue Anti-Persons who threaten “Status: Q”. The relation of these two levels of reality is a complex thing, and while I’m not entirely certain that this is the genesis of Morrison’s tendency towards parallel and mutually exclusive flows of reality, it is an early and strong answer.

Annihilator by Grant Morrison.

A decade after The Filth came Annihilator, a gothic haunted mansion in space. It centers around a devilish Arsene Lupin pastiche, Max Nomax, who has been banished to a prison orbiting a supermassive black hole, a former monastery whose prior inhabitants committed mass suicide. The only other entities there are Baby Bugeyes, a kind of living or robotic Teddybear left behind who is intended to offer comfort to those it finds, Olympia, the dead or comatose daughter of VADA (who is both God and Nomax’s arch-enemy), and Oorga, a kind of virulent anti-life imprisoned in the basement.

Except that it’s also the story of Ray Spass (pronounced “space”) a screenwriter who has just moved into a cursed house to work on a screenplay about Nomax that he is struggling to write, probably because he has a massive tumor in his brain. This tumor is, according to the hallucinatory figure of Nomax that Spass sees, a “data bullet” that contains the story of how Nomax escaped from his prison and came to Earth.

It’s a fun little story. I feel like it is easily overshadowed by the next one, but there is a kind of thematic resonance between the two that I think provides a good argument for reading them together. There are parallels to the plot, and I can’t help but feel that — unknown to me, at least — there is a third component in this hypothetical trilogy, a synthesis to the thesis that is Annihilator and the antithesis that is Nameless.

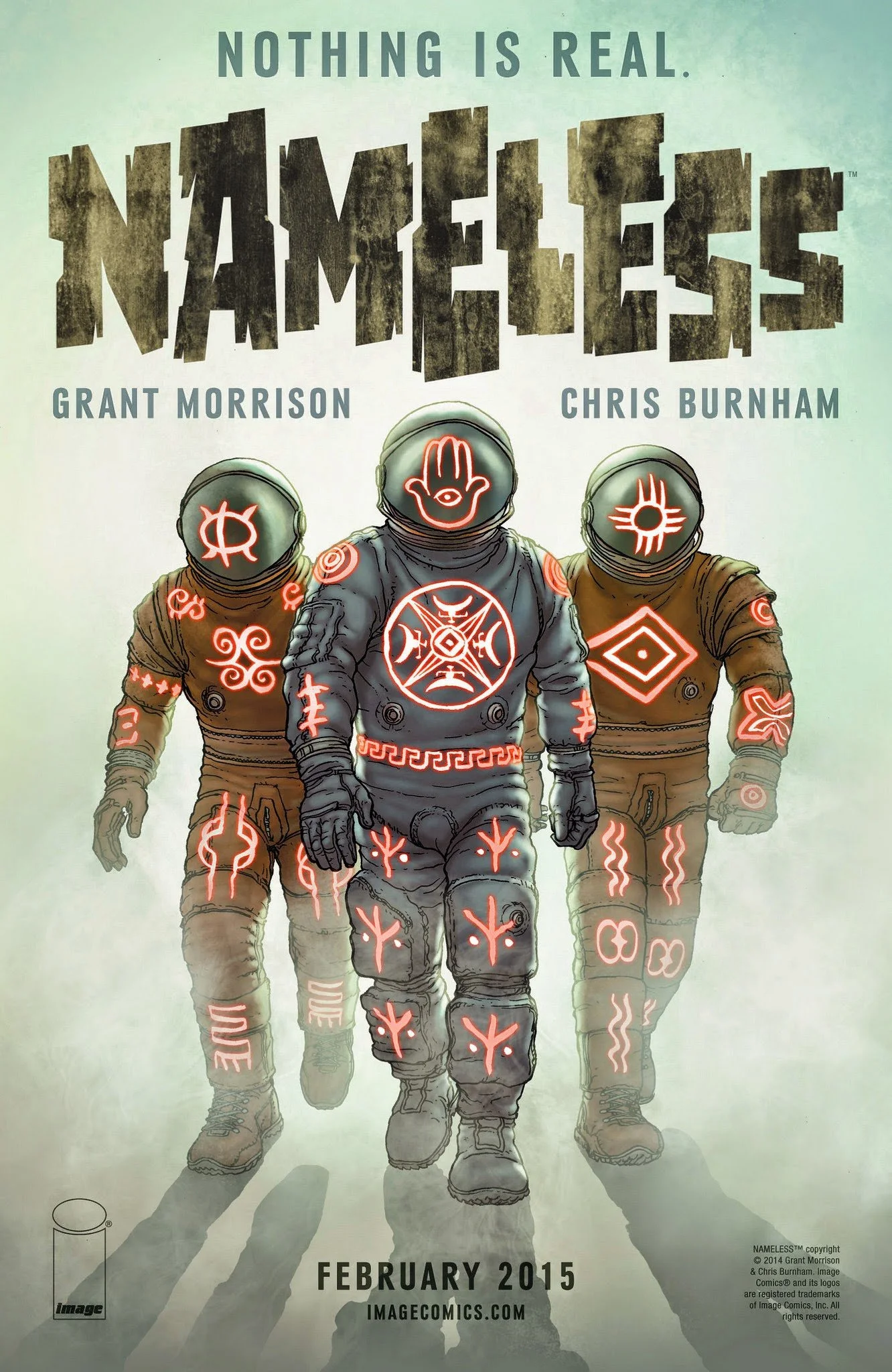

Nameless by Grant Morrison.

What to say about Nameless? It’s the story of a criminal ritual magician hired by a billionaire who is totally not Richard Branson to help deal with a massive asteroid that has a dread magical symbol carved into it by inhuman hands. It’s the story of that same ritual magician being recruited by that same billionaire to participate in a seance in a serial killer’s home as a kind of media stunt and being possessed by a violently insane entity that claims to the the god of the Christian bible. It’s also the story of that same ritual magician stealing an artifact from the ruins of Nan Madol and being captured and interrogated by Moray Eel cultists.

It’s a lot of things, and the plot lines are not neatly distinct or separated out from one another in a clean and simple way. Morrison builds up a mythology that is drawn in equal parts from Typhonic, Polynesian, Mayan, and Hebrew beliefs, in an attempt to create something that feels Lovecraftian without regurgitating another string of consonants and apostrophes. Part and parcel of this is the idea of many worlds stretched between the material world and the kind of absolute source of existence that one finds articulated in the Kabbalah.

So each of these stories, interweaving and intermixed are all metaphoric “faces” of some many-dimensional object, mutually exclusive but filtered through different genres and all discussing the same plot, sketching it out in a complex and multivariate shadow upon the comics page.

It isn’t that this story is happening now and that story is happening then. They are two shadows of the same inaccessible story at root that we have to derive and reconstruct as we move on, and there’s going to be a metaphoric remainder that can’t be easily reduced.

Last Exit by Max Gladstone.

(Reviewed first here, and by Edgar here.)

Honestly, this list is a set of poor reviews — there’s not one here I wouldn’t recommend, and as much as I enjoy looking at other’s enthusiasm, I can’t help but feel that discernment requires a certain amount of cutting. There are some here I enjoyed less than others, and then there is the opposite situation, exemplified by Last Exit.

I have wanted to reread this book since I finished it, mostly because there was no way to continue to read it and still be reading it. It’s the story of five friends who set out to fix what they see as an increasingly broken world, having learned to tap into a special power that allows them to hop from one possible world to another. They failed. Ten years later, one friend short but supported by the absentee’s young cousin, they go back and attempt it again. It’s a joyfully fun story that makes you feel genuine sorrow for the characters — where they fail, where they fall, and where they die — without being cloying.

This remains one of my favorite recent reads — free from the tendency of a lot of contemporary adventure fiction to make its protagonists agents of a larger organization, and putting genuinely interesting people in interesting situations where they grapple with the forces that make their world what it is.

In the Eyes of Mr. Fury by Philip Ridley.

(Reviewed by Edgar here.)

Edgar was, if I may be so blunt, far too brief with this book. I’d read the original version, but this one is the expanded, 2016 version, which is almost completely rebuilt from the ground up, made into something entirely different. It was excellent, but I had been expecting the original version, while this one is a different beast entirely.

The reconstruction of the text wasn’t bad, but it hits a different note from the original. It is more complete and more expansive text, dealing with the history of a small street in the East End of London and the lives of the people who live there, stretching from the earliest life of the aged Mama Zepp to the 1980s, shortly after the viewpoint character, Concord Webster, turns eighteen.

In the original version of the narrative, it felt to me that Concord was more of a protagonist, but in this version, he is much more a simple viewpoint character. Just about every chapter is an extended story told to him, relating events that happened long before his birth, in the unfolding life of his parent’s generation and the tangled love lives of his mother and the people she spent time with when she was Concord’s age.

I will happily recommend it, but I cannot recommend it over its original version: the two books are so different that it seems best to treat them as variations on the same fundamental set of characters and themes, separate from one another and reflecting different ideas of what the story should be. Both are worth reading, though I think that I might have preferred the original version to the second one very slightly.

The old edition, the one I have signed, not the new one.

American Gods by Neil Gaiman.

(Reviewed by Edgar here.)

Another expanded and updated version of a book previously read, but one that I haven’t touched since it was formative to me in my adolescence. I still have the mass-market paperback that I originally read the story in, dog eared, beaten, and signed by Mr. Gaiman at the Sigma Tau Delta conference in Minneapolis in 2009 — I came to support classmates then, and was spending a fair portion of my time holed up in my hotel room, using my headphones to blast my brain with the Mars Volta’s Frances the Mute and trying to pound out my senior thesis, attacking my laptop’s keyboard like it owed me money. Still, though, I took the time to come down and listen to Mr. Gaiman deliver his talk on his life as a writer and accept honorary membership in the organization. The copy of the book was already dogeared at the time and I debated not going up and getting it signed — I was embarrassed that I didn’t have a more pristine copy. Of course, it didn’t matter: a book damaged through extensive reading isn’t something to be embarrassed about.

Enough memory lane. I present this to you for no reason but to echo Edgar’s own idea that, sometimes, you read a book and it becomes part of who you are, and so rereading it becomes an act of self-recognition. This happens to me with American Gods, and a small slate of other books. They are part of the raw material with which I built who I am.

I don’t think I really need to recap the plot. Shadow, a prison inmate is released earlier than expected — he was scheduled out for parole, but his wife dies that same week, so he is released after three years. On the flight back, he meets a man who goes by Mr. Wednesday, who offers him a job, but Shadow refuses: his best friend, Robbie, has a job waiting for him at a gym back in the small town where they live. He discovers, though, that not only is there no job, but Robbie and Shadow’s wife Laura had been having an affair and had died together in an oral-sex-involved traffic accident.

Unmoored, Shadow accepts Mr. Wednesday’s job offer when the two inevitably meet up again. Thus begins an odyssey through America, where the two meet with strange people, marshaling powers for some great upcoming battle.

It’s no secret that Wednesday is Odin or Woden. The word “Gods” is right there in the title. It’s no secret, either, that in the world Gaiman draws, all of the folklore brought to America brings with it the Gods that people still believe or half-believe in. Beyond just the Germanic gods, we have figures from Native American and Hindu belief, Ancient Egyptian and Celtic mythology, and even some appearances from figures from the Abrahamic religions (though, as far as I can tell, the Islamic representation is limited to Djinn, which seems a good compromise between inclusion and the prohibition on representation). Gaiman even wrote a scene where Shadow meets Jesus — it’s included as an appendix to the most recent edition. Frankly, I think that it’s best that he cut it. While most of the adjustments are so minor that I didn’t notice any difference from the original, the Jesus sequence is jarring and thematically a bit wobbly. He discussed having put it back in for the rewrite and then removed it again, and, frankly, I think that’s the right call. The mention of seeing Jesus hitchhiking by the side of the road in central Asia was about the most that was really needed there, I think.

Ring Shout by P. Djèlí Clark.

(Reviewed here.)

Having read Last Exit and American Gods I wanted to continue the same general vibe, and re-exposing myself to Clark’s writing in Out there Screaming, I thought that revisiting Ring Shout would be a worthwhile use of my time. It was, of course: Clark is one of the best American writers of fantastic fiction active these days, in my opinion. My ideas have evolved somewhat from my first review, ultimately to the benefit of the story. I originally commented that I wanted a text longer than this, but I’ve come to develop a greater affection for the novella format — and not simply because I’ve set a reading goal this year with a higher threshold than I normally do.

No, I think the real realization is that the novella format is just perfect for some stories — and while I want more novellas about Maryse and her friends continuing to fight horrors in the early 20th century, I think that this first book was just about perfect for that. It’s not simply an adventure story centering on black heroines killing possessed klansmen, though it is that, and quite good at it, too: it explores a number of unique and fascinating aspects of southern American, and specifically Black, folklore, such as the Night Doctors. While the descriptions are visceral and chimeric, it lacks the inhuman orientation that you see in Lovecraft — or in the non-Lovecraftian Cosmic Horror approach seen above in Nameless. This is a horror and terror rooted in the human experience, though its manifestation is certainly inhuman.

Personally, I see no reason not to tackle this book. The hard cover is only 192 pages, and the audio book is about six hours in length. You’ll blow right through it and come away wanting more.

Too Like the Lightning (Terra Ignota, Book 1) by Ada Palmer.

Too Like the LIghtning positions itself as a history of a pivotal week in the history of the world, in the mid 25th century. In this world, gendered language has supposedly been abolished, as has the discussion of religion by groups larger than two people — and every person has a religious specialist, called a “Sensayer” who helps them develop their own personal theology, — and the nation state. This last has been replaced by a system of seven Hives — the Masons, the Mitsubishi, the European Union, the Cousins, the Humanists, the Brillists, and the Utopians — who all emphasize a particular set of values and are dispersed throughout the world by rapid point-to-point transportation through a system of flying “cars”. There are also individuals who pledge allegiance to no Hive, though are still represented in the world senate.

Into this world steps our narrator, Mycroft Canner, who is something like Hannibal Lecter wearing a shock collar, or Doctor Moriarty on a work release program. He is a self-confessed unreliable narrator, who one gets the sense is not simply unreliable but significantly incorrect in what he thinks is actually going on at points. Mycroft is a Servicer, a criminal who is unable to own property or engage in traditional commerce: Servicers are supposed to perform services for people and be paid in food. The nature of Mycrofts crime(s) are revealed later in the book, but it is clear from the beginning that he is infamous and often seeks to hide his identity. Frankly, if they were to film it, Mycroft would be the perfect role for Michael Emerson, who played Ben Linus in LOST.

Honestly, the plot itself is interesting — one half theological novel of ideas, one half futuristic conspiracy, told by a mostly-reformed but not specifically repentent criminal who has an unhealthy fascination with gender — but I’m still fascinated with the world described. Palmer shows us a world that is specifically better than what we have but is not positioned as, in any way, utopian (even the Utopians aren’t exactly utopian in orientation, many of them working fifty or sixty hours a week in pursuit of whatever dream they have.) Oftentimes, it is the tendency among speculative fiction writers to construct a better world and label it utopian, label it the “best of all possible worlds” and move on. Palmer, in this world and its fascination with the Enlightenment, satyrizes this Panglossian tendency before moving on to more interesting things, such as a conspiracy run out of a brothel that also houses a convent and a policeman who wields theology as a weapon.

I’m going to have to finish these books at some point. It was good to get a refresher first.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.