A Case For the Value of the Humanities (Contraslop, Part 2)

The Vitruvian Man, often used as a symbol of the humanities.

Last week, I discussed the way that technological development is misunderstood by most people – including those who are involved the most closely with it. By assuming that there is an inevitable progression toward some ultimate point, people are encouraged not to exercise agency over it. I spoke fairly extensively about Large Language Models (what most people call “AI”) in that piece.

Now, I am not an “AI expert” – I am an English teacher – but, against my will, Large Language Models are being used to complete work for my class, and so I have a stance. Oftentimes, demanding narrow expertise of those being effected by an issue or practice is used as a silencing tactic. Now, I am not against expertise, I happen to have it in several areas. I could enumerate them here, but that seems unnecessary to me. However, expertise should not be used as a means to silence stakeholders in a situation.

What I am saying here is not that expertise is not useful, what I am saying is that one very narrow type of expertise in this situation is overvalued, and every other variety of expertise is erased or undervalued.

Let me introduce you to a term: “domain expertise”. In data science, this term is used to refer to people who have expertise in areas other than data science. This suggests that data science is true knowledge, while all other things are a subordinate sort of knowledge.

You can find plenty of articles on LinkedIn and websites catering to data scientists, many of them warning of the danger of over-relying on domain expertise, saying that it can stifle innovation and lead to resistance to changes that are necessary for the growth of a business. It probably won’t shock you that every single one of these that I have tested with an AI detector – and when I test something I run it through three different detectors to get a broad based result – all of them came back as a minimum of 98% AI generated.

Which means that everything written about the danger of domain expertise was written by nobody. It was willed into existence by someone who simply didn’t care to construct their own argument.

Here’s a rule I follow, something I recommend that you adopt: if no one bothered to write it, no one should bother to read it.

※

My own proposal for a symbol for the humanities would be the chimp at a typewriter — filtering the chaotic, animal impulses we experience into something other people can understand.

The use of the term “domain knowledge” creates something that I tend to refer to as the “empty default”. Because it doesn’t actually imply that the opposite of Domain Knowledge is data science – it implies that the opposite is “regular knowledge”. Whenever something is defined as “special” in opposition to something “normal”, my hackles go up, because the “normal” thing is usually implied to be the default from which everything else is a deviation: it’s a privileged position.

Think about children’s shows from the 1980s, the cast of characters that you often see there. Oftentimes, you find the same spread: the hero or leader, the brooding second-in-command or rival, the strong one, the smart one, and the girl. This setup implies that being “the girl” is a quality like being “strong” or “smart”, it’s a deviation from a normative masculinity. While this might not be saying that there’s something wrong with being a girl, it’s saying that it’s a deviation. Meanwhile, masculinity disappears and becomes unspeakable – occasionally re-inscribed as something very particular, but oftentimes simply left invisible.

What is erased, paradoxically, becomes exalted.

What is necessary is a process of de-centering the invisible: by moving it out of the default position from which everything else is measured, its qualities become visible. What, previously, seemed empty, now becomes something full and specific.

Either “domain knowledge” doesn’t exist, or “data science” – and its close counterpart in these discussions, “business” – needs to be recognized as a type of domain knowledge.

※

Agnes Callard’s former twitter profile picture. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 license.

I started this on one of my days off – I decided to get going on this sooner rather than later, it’s Friday as I write this portion – and after waking up late, I decided to track down an article by Agnes Callard, written for the New York Times, entitled “I Teach the Humanities, and I Still Don’t Know What Their Value Is”, because I intuited that it might be instrumental to the argument I want to make here.

Because my issue isn’t, necessarily, that Large Language Models exist, my issue is why do I have to deal with them in my classroom when they universally produce substandard work? I think that the answer might lie in the fact that most students – and most administrators – don’t really understand what the humanities offer. They are simply a subsection of knowledge that are not necessarily useful in the world that we live in: they are, in fact, a domain, and have limited applicability outside of that domain.

To do this, I need to understand and be able to articulate why the humanities are necessary. Professor Callard goes through a number of reasons, and ultimately doesn’t feel that any of them quite hold water. She discusses the idea that they promote democratic ideals, that they improve leisure time, that they improve critical thinking skills, or promote empathy. I’ve found myself making all of these arguments at different times, but none of them seem entirely satisfying: they might end the discussion, or force a pause on it, but none of them quite do it.

Callard finishes up by saying that she doesn’t exactly know why the humanities are important, though she feels that they are. This boils down to her asserting that the core of the humanities is a questioning stance toward the world, while justifying the position requires a certain defensiveness.

Let’s flip this on its head momentarily.

A business degree doesn’t lead to better outcomes: CEOs with MBAs are more likely to engage in behaviors that enrich themselves and harm their companies, and the only measurable effect really seems to be lower employee wages and lower employee satisfaction. An MBA degree is a net negative, when viewed objectively.

Gordon Moore’s face, used (inexactly) to graph Moore’s law — from Steve Jurvetson and used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 license. For those unfamiliar, Moore’s Law is the broad statement that due to shrinking transistor size, computing power doubles every eighteen months or so.

As for computer science, we’re entering the tail end of a period of acceleration. Moore’s law is dead, and the AI bubble – as my last post and prior posts I’ve put up – is already popping, because we’ve already seen the metaverse and cryptocurrency: the tech industry is out of tricks and people are getting frustrated at executives trying to convince them to become bag holders.

Pure mathematics is as applicable as philosophy. Sure, you can derive other things from it, but — as pure research — it belongs closer to what I’m arguing than what they’re arguing. As soon as they kill the humanities and social sciences they would take the cleaver to the mathematics department.

What’s the point of the humanities?

What’s the point of STEM and Business?

Going down this road just means that every university becomes a nursing program with parasitic faculties of accounting hanging off of it.

The point of education must be more than simply its immediate, pragmatic application. As soon as we reduce it all down to what produces a fat paycheck, we have to grapple with the fact that a college degree has less to do with wealth generation than we tend to think.

A lot of the fault for this can be laid at the feet of US News and World Report. As Philosophy Professor Thi Nguyen noted on an episode of Conspirituality that he appeared on, before schools were ranked on a particular set of metrics they specialized in different things: now that they’re focused on the same metrics, they all work the same way: what was originally a tool to allow a certain kind of middle-class parent encourage their child to adopt a specific attitude towards education has become a the way that all colleges are “objectively” ranked.

But as soon as you adopt a metric, other things begin to fall out of it: you optimize for that particular metric, that one thing. All of a sudden, the diversity is lost, all of a sudden, there’s simply a monoculture.

Now, instead of education being about developing as a person, it’s about maximizing earning – though we still call that developing as a person. From this standpoint, the humanities makes no sense. This standpoint, however, is endemic to the ideology of the neoliberal atomized individual: it’s about maximizing your own wealth at the expense of everyone around you. It’s the same ideological grounding as leads to climate change and for-profit healthcare.

What is the use of the humanities?

Let’s stop looking at “humanities” and start looking at what you mean by “use”.

What does it mean for something to “have use”?

※

I’m reminded here of Bookchin’s critique of instrumental reason, though I’m still grappling with that a bit. Viewing things in purely pragmatic terms – what can this be used for? -- is easy enough to do, but I think that there’s a flaw in it: if the question is only about means, how does one decide upon an end? What is worth putting your effort towards?

Sure, let’s drop the critique of non-humanities degrees: what is it that their proponents always argue in favor of? The fact that they can get a “good job”. However, different people achieve satisfaction by different roads.

My summer job this year is the same as my job from last year: I am driving around and watering trees. During the driest parts of the summer, this means taking water from the KC parks building, which has brought me into contact with a number of people who took a radically different life path from me: they wake up early and go work outside, doing maintenance on the parks. They’re well-paid and have skills that I never acquired (and somewhat doubt I could acquire without a great deal of effort): it’s rewarding work for them and at the end of their working life, they have a solid pension waiting for them.

I have another friend who wakes up at 5AM to do data analytics for a company based in Eastern Europe and finishes by early afternoon. Still other friends don’t go into work until 4PM at bartending jobs. All of these are valid approaches to life. Some of them require degrees, others require long and arduous apprenticeships.

However, to say that one of these paths is “correct” and the others are not is quite simply wrong. They’re all different means to the same ends. And that end isn’t financial stability – financial stability is, itself a means to the end of living a life you’re satisfied with – and I am not using “satisfied” here to mean a kind of post-consumptive contentment, but to mean the state of feeling that you would prefer not to have pursued something other than what you did (so, I suppose, the absence of FOMO). To claim that the humanities are a bad investment of time and energy is to say that they don’t, ultimately, lead to that state of satisfaction. This, likewise, is quite simply wrong.

Of course, to a certain extent, this is still falling victim to a kind of instrumentalism, and is, itself, still very focused on the individual and their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their own lives. I’m still not entirely comfortable moving out of the pragmatic frame, but let’s say you’re not able to move out of it to even this extent: let’s say you can’t think in terms so abstract as “what leads to a person being satisfied with their own life?”

Is their a pragmatic reason for engaging with the humanities?

※

Allow me to put forward a theory.

There are (at least) two kinds of knowing and reasoning.

The dominant kind of “knowing” is quantitative. What is countable, what are the magnitudes at work here, so we can reason what is happening, what is the statistical likelihood that what follows the “F” is a “u”?

The quantitative kind of knowing might tell you that there are seven hundred and eighty-two grains of sand on the table in front of you.

The other kind of reasoning is qualitative. It’s not a question of numbers, but a question of impressions and priorities and understandings. This is what’s happening, what is the meaning of the event? This is what word is here, what’s an appropriate response.

The qualitative kind of knowing might not be able to guess at the number of grains of sand, but it can tell you whether it constitutes a pile or not.

Formerly, we lived in a qualitative world. The world was enchanted and everything had significance. The downside, of course, was all of the war and plague and famine. None of us, I don’t think, would really want to go back to the middle ages (yes, I know peasants got a third of the year off, but are you under the impression that they could call a roofer if a leak woke them up in the middle of the night or that the cow didn’t need to be milked on the Feast of Saint Whoever? They worked quite a bit) but to think that moving all the way to the opposite end of the spectrum is an improvement is a fallacy.

For reference, please see Alex Birchman’s classic “Torment Nexus” tweet.

Simply because something is bad doesn’t mean that its opposite is necessarily good. It’s possible for the opposite of something terrible to be something equally terrible. 1984 and Brave New World are both bad – but the society of the former wanted to abolish the orgasm and the latter wanted to abolish everything else. If we add a third point on the scale, we could consider The Handmaid’s Tale, which is opposite the other two and equally bad.

Of course, if you lock yourself into thinking that quantitative reasoning is the only valid reasoning, you may not be able to see what I’m getting at. You’ll be stuck in the mindset that the only valid use for your time is to find a way to find a way to improve the specific metric that you have adopted as your particular white whale (leaving aside that this tends to result in other metrics – or even unmeasured qualities! – being neglected and worsening.)

This results in the AI-related thought experiment called the “paperclip optimizer”. A super-intelligent machine tasked with creating paperclips and not given appropriate additional conditions may simply decide to convert all matter in the universe to paperclips. This is, of course, stupid (why build such a machine?) but it illustrates the problem with the mindset of the people engaging in this space: the question of “why” is never considered, the idea of guardrails being put up before building it is treated as a novelty, and they always question how to do this “responsibly” instead of asking whether it should be done in the first place.

You can just not go to the trouble of letting the genie out of the bottle. You have to build both the genie and the bottle and no one involved – yourself included – wants this to happen.

※

That last bit got far afield, and wasn’t adding anything new, but I want to zero in on something in particular here. Let’s reset to the basic question: what to do about LLM writing in a college English class?

The real problem is different from what you might think.

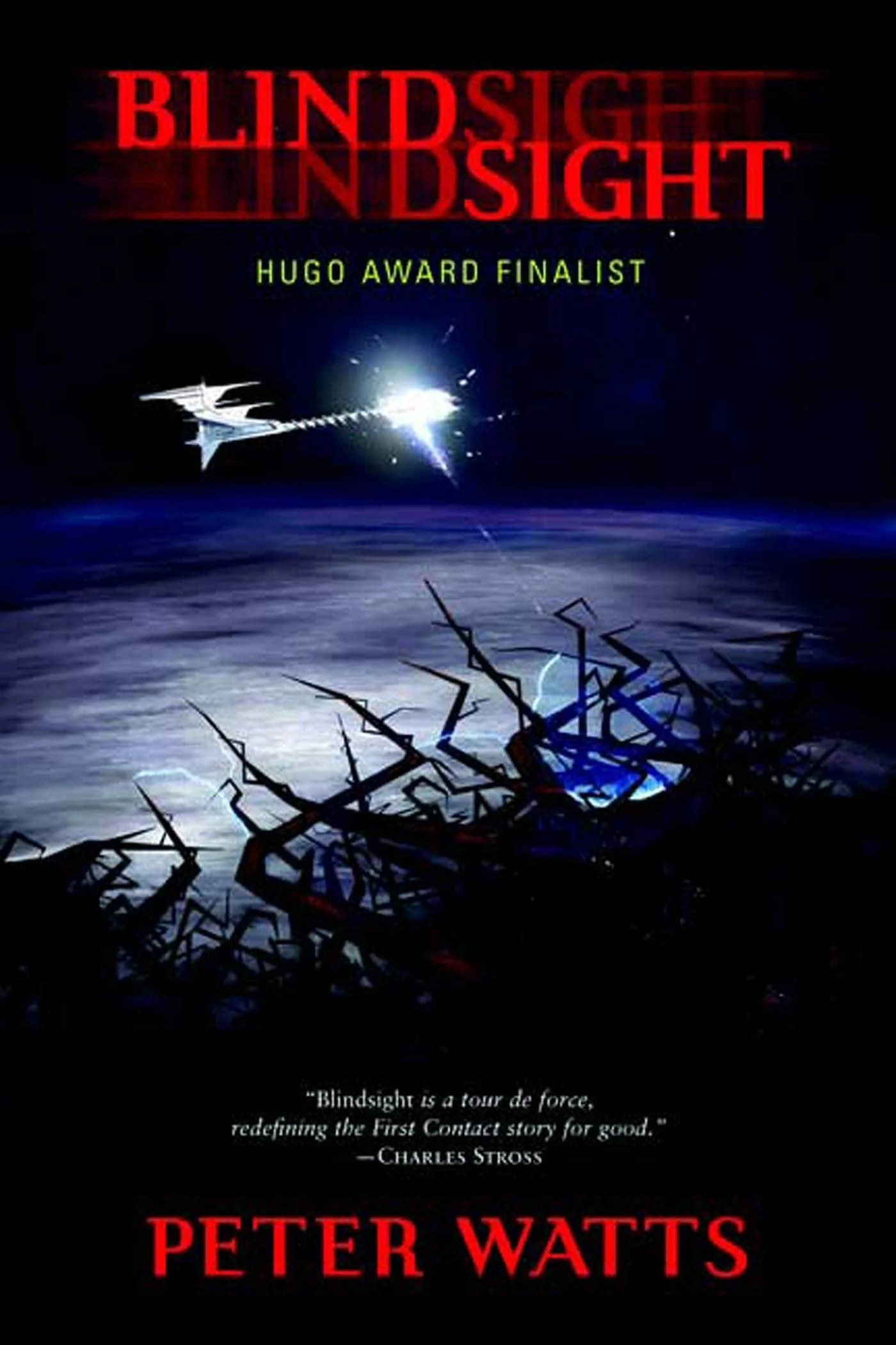

This book has been distressingly useful for me as a way of thinking through the world.

Here’s the real problem: if a task can be replaced with an “AI”, then it’s already an AI, just with a person taking the role of the computer, similar to the bit about the Chinese Room experiment in Peter Watts’s Blindsight.

The move in pedagogy, to make things more legible and responsible, has been to try to reduce all things that are important in an assignment down to something that is visible on the page and enumerated in rubrics. This takes what was previously mêtic and makes it technic, it makes it visible to the statistical engines that people are calling AI, and even if it can satisfy the visible requirements on the page it doesn’t produce writing worth reading.

Which means two general things:

First, the people who set up these machines don’t actually understand the topics that they’re trying to automate. They think that this knowledge is a type of subordinate “domain knowledge” less useful than the “generalized” knowledge and skill that they possess. This leads to myopia where it does a terrible job but they can’t tell that it’s doing a terrible job.

Second, it indicates that the way that writing it taught leads to bad writing. There are, of course, people who are good writers, but they have advantages that allow them to take advantage of the pedagogy. I would submit that the people who improve are already interested in writing, while the people who don’t have been discouraged from it.

As such, I find myself upon the horns of a dilemma. By “rationalizing” the assignments to make them more understandable and accessible to students who do not conceive of themselves as skilled writers, I have inadvertently made the assignments more legible to the inputs of Large Language Models, and experience has taught me that within a class of fifteen to twenty students I might have as many as five students who decide to risk punishment equivalent to a plagiarism strike.

My goal is not to mill through students and reject those who do not understand, it is to teach. If a student is exiled from the class, then they cannot learn.

Clearly, what is necessary is to find a way to “leap” from the simple, rules-based approach to one that requires a deeper engagement with the material – which I’m certain can be done, but it is much more difficult without knowing the people to be persuaded first.

I am going to leave this piece off here. Next time I write a piece of this sort, I am going to try to define what I mean by this “leap” and the nature of the “deeper engagement” that I mentioned.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.