Compulsory Electoralism Column: Summer 2024 Edition

The apotheosis of Washington, which I used in the American Cringe piece that I wanted to reference here, but failed to get into this draft. Originally uploaded to wikimedia commons by Constantino Brumidi under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license.

I’m going to be taking a brief break – two weeks or so – from the series about figuring out my AI policy. I’m still thinking through some things on that front, but it will be ongoing. Next week will probably be a book round up (Edgar did one, so I’ve got to, as well) but I feel the urge to discuss American electoral politics again.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “you and everyone else. I don’t care, get back to talking about something inherently interesting, like game design or bizarre pseudo-philosophical tangents.”

Bear with me, I’m going somewhere with this.

I mean, I’ve sworn off electoral politics eleven or twelve times at this point, but I always end up going down to the polls even though, as a Missouri resident, I’m aware of the fact that my vote isn’t going to matter in a national election. Clearly I need some kind of therapy.

While I don’t have thoughts I’m going to share about what either of the octogenarian candidates should be doing – frankly, they should both be retired at this point, and I think everyone involved knows that – I do have some general thoughts on the tactics of electoralism and how we ended up in our current, increasingly dire, situation.

A lot of canonical leftist analyses of electoral politics are based on the British and French systems, and while they’re not completely different (I definitely hope that the results of the American elections this year hew closer to those of Britain and, especially, France) there are some key differences that need to be kept in mind. Both Britain and France have parliamentary systems, which are friendlier to the presence of minority parties and have shorter election cycles. The American system, on the other hand, is hostile to smaller parties (in fact, I think that it’s easier to get elected as an independent than as a member of a third party, which is a puzzling fluke of the system) and we’ve got it set up so, while legislation moves slowly – the idea being that, in such a situation, “cooler heads will prevail”, we are in an almost constant election cycle.

This makes electoral politics almost impossible to ignore because, frankly, people don’t shut up about it.

※

First, stop pre-compromising.

One of the Democrats’ favorite thing is to compromise before the debate begins. Oftentimes, this is done to appeal to the Republicans, who will not compromise at all, or to internal enemies (Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema) who should, properly speaking, be Republicans.

It makes a certain amount of technocratic sense. Imagine a frictionless, perfectly spherical legislature – by which I mean a normal legislature, but everyone involved is a sort of genderless, homogeneous, lanyard guy, divided into red team and blue team. It makes sense, in such a situation to look at your starting position and their starting position and just propose something that’s approximately 50% between the two positions and then knock off early to go drink Martinis and play golf or something.

This guy was the king of the pre-compromise in the 21st century.

But when your opponent has serious ideological differences – when they want the country to end up someplace fundamentally different from where you want it to end up – you need to actually start from a legitimate initial position and then proceed from there. You need to go through the whole theater of debate and back and forth so that you arrive at the middle position, instead of trying to start from there.

If you begin from the middle position, it becomes your position, not the middle: you will be dragged to the new middle, which was originally the 75% mark. This desire to compromise results in a ratcheting effect – the Republicans pull right, the Democrats try to meet them in the middle, and end up shrinking the gap further and further. Meanwhile leftward movement becomes impossible.

Look at the removal of the Public Option from the Affordable Care Act, designed to appeal to internal enemy-turned-independent (and proxy for the insurance industry) Joe Lieberman. Look at the history of the Build Back Better Plan, and just how much of it was jettisoned before it actually made it to a vote.

※

Second, the fringe is a resource, not a liability.

Okay, look, a lot of people are going to write me off for this, but it’s not just me: a lot of analysts think this, and I’ve heard it articulated most recently in Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline. We tend to think of Martin Luther King, Gandhi, the Suffragettes, and the Abolitionists as achieving their ends without violence, but this erases the concurrent violent movements (or extreme strands within the movement).

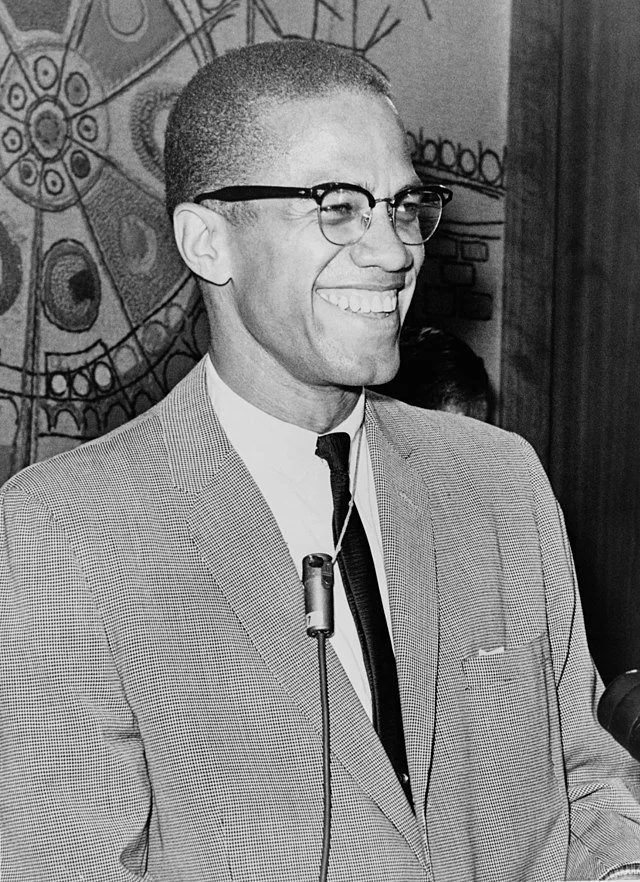

I’ve got a fascination with Malcolm X, partly because I use part of his autobiography in my composition classes. Despite my characterization in the body of this text, I have to admit that his rhetoric seemed to be a bit more violent than his actions.

Without Malcolm X, Martin Luther King wouldn’t have made it as far as he did. Without John Brown, the northern Quakers would not have been able to make the case that slavery was a moral ill: they would have been painted as extremists without a real (and justified) extremist to stand next to.

This is a lesson that the right wing has known for a long time – hence why you don’t often see crack downs on the Klan and Neo-Nazis unless they’re getting real out of pocket. We need to acknowledge that their presence is, at the very least, not objected to: historically, there is a close affinity between law enforcement and white supremacist groups, and the FBI and similar organizations tend to either fail to address it or are actively directed to ignore it.

This means that the right fringe has a pathway into the Republicans proper. No equivalent pathway really exists on the left. This kind of symbiosis is not allowed: part of this is due to the relatively heavy emphasis on ideological purity from the left fringe, but another part of it is that the leftward fringe tends to be the only real group with a transformative politics. By definition, reactionaries want to go back to how things were. The leftward fringe wants to push forward to… admittedly the kind of social spending and labor power we had back in the middle of the last century. But they think it’s revolutionary.

Revolutionary is, quite simply, not allowed. You can invoke it, you can talk about it, but you’re not allowed to do it. We like the revolutionary on a symbolic level, but actual revolution upsets the status quo, and that’s a problem.

With the Republicans using their fringe and the democrats not using theirs – alongside the first issue outlined above about pre-compromise – is it any wonder that the Overton Window has shifted as far as it has to the right?

Here’s the issue: we don’t have Liberal and Conservative parties in the United States. We have a party with a liberal wing and a conservative wing, and we have a reactionary party. There is no broad-based leftist movement with any effect upon American politics.

Which is a problem, because – in my experience – there are more people who could be described as “deactivated leftists” than are commonly acknowledged. They might be inclined, in their hearts, to something like social democracy (why don’t we have a social safety net like they’ve got in France and England?) or something further afield. However, they know that the best they’re going to get in American politics is someone who tuts in disapproval if the price of bread rises more than about 2% every year. This person won’t do anything about it, but they’ll at least look unhappy about it.

So, gradually, these people get deactivated: their plans for improving their situation shrink from socialized healthcare to stealing toilet paper from work.

Do you remember that in 2020 we had a bunch of middle aged moms street fighting the cops in Portland? That energy is still here, it’s just buried.

This contingent almost got several wins in 2020: some light broke through the cracks, and they began to flex their muscles. It felt so apocalyptic at the time that I called that time “the burn down”, because it felt like everything was about to tip – and I have a habit towards hyperbole, which I admit – but I want you to ask yourself something: doesn’t it feel like a whole bunch of people woke up for a moment took some rather extreme and shocking steps in the right direction, and then the past four years has been all about putting that force back in its bottle?

It sure as hell feels like that to me.

And I think that’s part of where the resentment towards the sitting president comes from.

You can’t LARP the revolution.

Especially not in a power tie.

※

Finally, and this is directed more at the fringe (Active or Deactivated) than the center.

Politics come in both material and symbolic forms.

Material politics involves a lot of things – including things people don’t really think of as politics, like the way your workplace works and how you think of your family being structured – and most of it matters a lot. The arms being sent to Israel and Ukraine are an aspect of material politics, as is the aid the US government sends abroad.

Symbolic politics is what we can actually effect and, under the neoliberal logic that has held true since about 1980, this is all that we really acknowledge. This is where the shaking of the head and the tutting comes from: we’re only allowed to accept that the symbolic politics exists. We pick a figurehead, and our foreign policy changes.

Honestly, most of our domestic policy stays the same, we just justify it differently.

It should, of course, be noted, that symbolic acts — especially those that can have an impact — don’t necessarily come without danger. Indeed, as we can see from the case of Aaron Bushnell, sometimes that’s the whole point. Image from wikimedia commons user Elvert Barnes and included here under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 license.

Voting is a purely symbolic act. Calling your congressman is a purely symbolic act. Perhaps enough symbolic acts can have an effect: going up to the mic in a public hearing and shouting at someone who deserves to be shouted at is a pretty good thing to do, and might convince them to be slightly less terrible. It’s certainly safer to go this way than it is to take a book like How to Blow up a Pipeline at face value and try to do what the title says: that’s a great way to meet some very unfriendly men who all have the same very bad fashion sense.

But symbolic actions can also act as a release valve for what I’ve called “libidinal pressure” in the past. You go into seclusion, you make your choice, and then you wait for the results to roll in over the course of the next eight to seventy-eight hours, generally while drinking. It feels stressful. It’s like pacing the waiting room outside the surgery. It’s like standing lookout. You’re convinced that something is being done and that your symbolic action can change things (I’m not denying the possibility, mind you).

Are you perhaps burning fuel that can be used for other, more material actions, though?

Maybe not vandalism and arson, but could it be useful for organizing with a tenant’s union or doing some mutual aid?

After all, regardless of who’s elected in November, people in your community will still be hurting. People abroad will still be getting killed with weapons that these ghouls made you pay for. They want you anxious and locked in to their electoral game, and they refuse to play it to win.

Don’t let these awful, faraway people tell you how to live. Try to make what difference you can. Try to work with other people to do it.

Maybe that looks like voting, maybe that looks like something else.

But all we can do is try.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.