Satanwave: The Horror Genre Your Mother Always Warned You About

We’re big fans of horror films here – Edgar and I have been trying to make it through the summer without central air, and this has necessitated asking for help: one of the most common ways we receive that is going to sit at a friend’s place and hang out with him while he works through an absolutely titanic backlog of films.

Lately, though, a pattern has begun to emerge from the random noise: when you see similar features crop up over and over again, you can begin to see the shape of a genre – or subgenre – that may indicate something about the way that culture is moving.

Recently, we caught Longlegs (dir. Osgood Perkins) in the theater, as well as – on various televisions – My Best Friend’s Exorcism (Damon Thomas), Late Night With the Devil (dir. Colin and Cameron Cairnes), and Historia de lo Oculto [History of the Occult] (dir. Cristian Ponce). All of these films are period pieces that deal, directly with the Satanic Panic and their fictional conceit is that these fears were justified by the existence of actual supernatural forces being active within the world.

I have decided, personally, to think of this genre as “Satanwave”, in reference to New Wave Science Fiction of the 1960s and 70s, New Wave music of the 1980s, as well as more contemporary Vaporwave, Synthwave, and similar genres. This terminology came from referring to a new variety of a media being considered its “new wave”, but has shifted somewhat. The fandom site Aesthetics Wiki suggests that the “-wave” suffix “symbolizes shifts within a genre, reflecting a major change in its style. It denotes unique evolutions within a larger aesthetic”, which is both a fair point, and almost useless for our purposes.

Instead, I propose that we should think of “X-wave” names as, essentially meaning “operating as if X is true or hegemonic”, where “X” is a one-word summation of the central conceit. So “synthwave” is “operating as if synthwave is hegemonic”, or — to put it in less theory nerd terms — music from an imagined alternate history where Grunge and Rap never displaced New Wave. It gets more complicated when we’re looking at more purposefully obscurantist genres like “vaporwave”, but for many contemporary “wave”-suffix genres, this seems to be the best way to understand them. Ergo “Satanwave” is “operating as if the satanic panic were true.”

Let’s take a brief look at each film, in order of the film’s release. After that, we’ll look at what features are common among these different films and build a conception of the genre based on that.

Historia de lo Oculto (2020 – North American release 2022)

This movie slaps, by the way.

Chronologically the earliest of the films I’m considering closely, History of the Occult directly name-checks Mariana Enriquez’s Things We Lost In the Fire, and the influence of Enriquez’s work. The majority of the film is pegged, temporally, to the final broadcast of a late-night news program called 60 Minutes to Midnight, but the film largely concerns a team of researchers attempting to put together the last piece of a puzzle, to be revealed at the end: they are led by Professor Adrián Marcato (Germán Baudino), and the team primarily consists of the skeptical María (Nadia Lozano), the shell-shocked Abel (Casper Uncal), the easygoing Alfredo (Héctor Ostrofsky), and the daring Jorge (Agustín Recondo). They’re all waiting with baited breath on updates from the one of them currently in the field, the inexperienced Natalia (Lucía Arreche).

I wish I could attach more actor names to their characters – I loved this film, but the resources to do so are somewhat outside of my reach. It’s an Argentinian film and is such a tight, well-structured, well-executed narrative that I’m incredibly impressed by it. The backdrop of the movie is a fictitious period of Argentinian history – the Belasco dictatorship – that appears to match the 1970s, and the suggestion throughout the film is that President Belasco ascended to his position through the use of witchcraft.

Being what essentially amounts to a journalistic/political thriller with occult elements, there are twists that I am reluctant to reveal: the ultimate conclusion sideswipes you unexpectedly, and I strongly recommend going in blind.

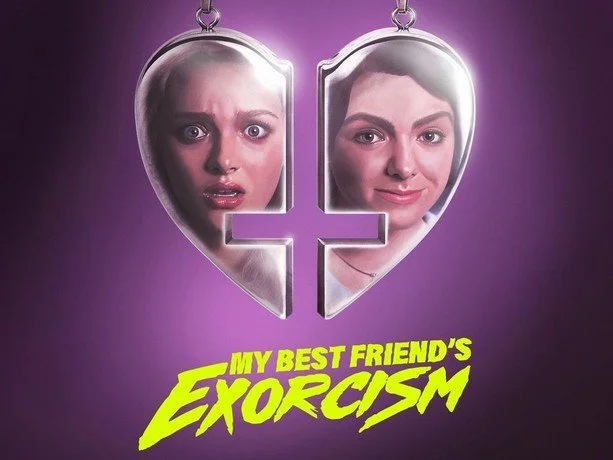

My Best Friend’s Exorcism (2022)

Despite coming after the first entry of what I would call the genre proper, I would call it, possibly, the last example of a precursor or proto-genre that developed into Satanwave. This is very enlightening: with texts that fit a genre, we can look at what is present, and use that to build a definition. With almost-fits, though, we can look at what is missing and use that to explain why it doesn’t fit.

So, the story: the film is a 2022 adaptation of Grady Hendrix’s (the same Grady Hendrix who did Horrorstör, which we generally enjoyed) 2016 novel of the same name. It centers on two high school aged girls – Abby (Elsie Fisher) and Gretchen (Amiah Lang) – who are presented as relatively average young women. One night, while at a lake house with two friends and the unlikable boyfriend of one of those friends, the girls ingest LSD and Gretchen wanders off before claiming the next day that she had been attacked by a monster. She then begins to behave in an erratic and cruel fashion.

The film features a theme of demonic possession and a 1980s-period setting, but closely hews to the beats of a high school film, and its fidelity to that particular genre, along with its comic tone and relative aesthetic normality, keep it outside of the Satanwave genre. It’s a perfectly fine movie – a solid B, I’d say – but it lacked key elements for inclusion, though it makes an excellent point of comparison.

Late Night With the Devil (2023)

A Shudder original, and featuring some extremely impressive large-scale accent work. It’s an Australian production, but they did their best to present themselves as Americans with a background in television, which accounts for a certain amount of uniformity of accent (the American Midwestern accent is the USA’s “prestige” accent, after all, and television presenters try to adopt it as much as possible.)

The framing device of the story is that it’s a documentary of sorts: we’re being presented with footage from the final episode of a late night variety show called Night Owls, which was also, coincidentally, a Halloween episode. The host of Night Owls is Jack Delroy (David Dastmalchian), regularly backed up by his loyal second banana and band leader Gus McConnell (Rhys Auteri). The guests for the evening are celebrity psychic Christou (Fayssal Bazzi), celebrity magician and skeptic Carmichael Haig (Ian Bliss), and a real get: a parapsychologist (Laura Gordon) and the cult survivor she is treating for demonic possession (Ingrid Torelli).

This film, in many ways, rhymes with History of the Occult – there’s the late night television angle, the near real-time, the satanic panic elements, the period piece nature – but as it centers on a variety program instead of a news program, the timbre is different. Late Night With the Devil also focuses on conspiracy theories more legible to an Anglosphere audience and has a much more sensational, special-effects-rich ending.

In many ways, it makes sense to see it as a sort of linkage between History of the Occult and the following film, though I would encourage you to see it on its own and see it as itself instead of as a simple step in evolution.

There was a bit of a scandal with this film, as the crew used AI to generate the title cards — which could have been a good entry point for a young graphic designer. In my mind, this seems like a good place to just say that they shouldn’t have done it, instead of writing the movie off entirely. The directors have addressed this, and claimed that only three images were generated in this fashion.

Longlegs (2024)

I’m going to refrain from sharing anything but the broadest summaries of this movie’s plot, as it’s technically still in theaters. It’s been most commonly compared to The Silence of the Lambs, but I feel that it more closely matches the Bryan Fuller Hannibal series – which I understand is a quibble, but I tend towards edge cases, quibbles, and parentheticals. To clarify: this stems largely from Maika Monroe’s performance, the character’s living situation, and her character’s relationship with other agents involved in the case.

Again, broadly, an FBI agent (Maika Monroe) pursues a serial killer (Nicholas Cage), who is responsible for a number of murders that involve one parent of a family killing the other members of the family. The similarities between these killings suggest a connection, but there’s no evidence of a third party being present in the houses that can be linked to a killer.

As part of a set, it might seem to resemble My Best Friend’s Exorcism more than either of the other two, but I think that it should be considered as a proper part of the Satanwave genre: the use of superseded media form is not the necessary component in the genre as a whole, rather what is needed is a certain heightened quality to everything. In addition to Nicholas Cage, who brings a camp element to just about everything he’s in, there’s also a fairly prominent early scene (I’d be surprised if it was more than 15 minutes into the film, solidly in Act One) that communicates that the film is set in the 1990s by having a large photographic portrait of Bill Clinton prominently featured – a later scene communicates its era by having a large, framed portrait of Richard Nixon. These elements create a childlike, exaggerated sense of the decade that feels weirdly (and, I would argue, intentionally) disjointed from the rather violent and adult subject matter of the rest of the film. It doesn’t hurt that there’s a kind of Satanic cast to both of these presidents (Richard Nixon is a shorthand for the overlap of evil and the presidency, and in light of his flights on the so-called “Lolita Express” and the victimization of Monica Lewinsky, I don’t think that Bill Clinton is being too fondly remembered these days – nor will he be in the future.)

Other Potential Entries and edge cases

The House of the Devil (2009)

Hereditary (2018)

Suspiria (2018)

The First Omen (2024)

Immaculate (2024)

The Quiddity of the Genre

“Okay,” one might say, “these sound like interesting films you’ve watched, but what binds them together into a ‘genre’?” In short, what is the quiddity that binds together their diverse haecceities?

At root, they all start from the point of assuming that — in-fiction — the Satanic Panic was concerned with a very real problem, that there is a dark force of some variety that is analogous to the devil as articulated in Christianity. Oftentimes, this takes on a somewhat Manichean character — Late Night with the Devil name-checks Abraxas, which is a name of the true god in the texts of the Nag Hammadi library and was treated as a deceiving demon by more orthodox Catholics. The exact theology doesn’t matter: what matters is the invocation of the Satanic Panic.

Beyond just the presence of the Satanic Panic, there is the awareness of it as a particular historical trend. The most successful of these movies don’t simply make themselves period pieces, they take it further and present themselves as fictitious artifacts of that time. They aren’t pretending to be nightmares about that period, they are pretending to be nightmares of that period. Consider the way that they’re shot — the aspect ratio shifts in Late Night with the Devil, the grainy black and white of History of the Occult — and understand that these are intentional choices being made by the people creating the films. For these two films — and I would argue, to a much lesser extent for Longlegs — this makes them also examples of Analog Horror, which we’ve written about in the past. However, what I think is important here is that this isn’t exactly nostalgia, this is what Edgar and I have, in the past, referred to as metachrony. There is not a dream of past eras at work here, there is an out-of-timeness that makes them feel strange and off-putting.

Potentially, I guess, it’s also your jukebox? The use of the devil in advertising strikes me as unusual, but apparently it happens (image taken from wikimedia commons)

Finally, there is a pervasive interest in conspiracism present in these films: it isn’t just that evil forces are real — that’s almost besides the point. The real problem isn’t the objective reality of evil as a positively existing force (as opposed to the Augustinian “absence of good” way of thinking about things), the problem is with people actively choosing to engage with and serve these forces. There are lone wolves, sure, but there are also cabals, covens, cults, and conspiracies that are responsible for what is happening. The evil isn’t just some cartoon man with candy-red skin, horns, and a pitchfork: it’s potentially your neighbor, your coworker, your boss. There is culpability to grapple with.

Summation

I think it’s important to note that many of these films are in conversation with earlier films of a similar style. It isn’t worthwhile, I believe, to go over the reference that Suspiria and The First Omen make to their precursors, but the majority of these films make at least a passing reference to Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist. These films discuss a certain amount of anxiety relating to young people and their development: a fear that their worldviews are being twisted by dark forces toward something evil.

Hey, do you remember how it was revealed that everyone from Bono to the President of Liberia were hiding money in tax havens all over the world, and the only thing that really happened was that Maltese journalist getting car-bombed and that Slovakian journalist getting assassinated? (image is from VectorOpenStock, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.)

In many ways, I think this parallels the development of Q-Anon, which I feel springs from a particularly heady ferment of suppressed anxiety about the Panama, Paris, and Pandora papers, as well the whole Jeffrey Epstein saga. This was pushed down, and returned in an uncanny, mutated form as fodder for broader right-wing populism. Many people have noted that this – especially in its earliest “pizzagate” stage, closely resembled the form of the Satanic Panic (compare the conspiracies around Comet Ping-Pong to those around the McMartin Preschool.)

Given the tendency of people on the internet to sort of yes-and the theories put forward, and the number of people involved in this who were alive for the Satanic Panic – some of whom were responsible for spreading anxieties around it and might have let it slip from their minds, but who never exactly decided they don’t believe in it – this makes a certain amount of sense.

But these people aren’t the audiences for these films.

The predominantly Millennial and Zoomer audience for these movies either has only loose memories from this time or simply wasn’t alive then. To them, this is just sort of the background radiation for their lives. I can only really speak to the peculiarly American elements put forward in Longlegs and Late Night with the Devil (which is in conversation with Americanness despite its Australian origins), but I would imagine that there’s a similar thing going on with History of the Occult.

Perhaps the conspiratorial angle is a sort of backhanded comfort: the deck has been stacked against you since the start by powers beyond your comprehension, so maybe it doesn’t matter so much that the world sucks – there’s someone responsible. It isn’t about us, it isn’t about abstracted social forces, it’s about them.

Of course, this runs headlong into something else: in many of these films, the climax is explicitly apocalyptic. This isn’t just nostalgia, this is nostalgia for the end of the world. At this point, I’m almost obligated to put forward the quote that comes from either Fisher, Žižek, or Jameson here: “it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

However, this isn’t the central thing, the most important thing, this is a distant secondary or tertiary factor in the analysis. Because, remember, these are all period pieces. To put the end of the world in the past is to put yourself outside the world, it’s to adopt a post-apocalyptic, over a post-modern, point of view.

The world that is presented to us has ended. We live in its wreckage. For a time, everything appeared clear-cut and balanced by the tension between opposites, but this broke down in a period of all-destroying monism.

But at the same time, I can understand why someone might find apocalyptic images comforting. This isn’t the tendency of people to imagine themselves as rugged sole survivors wandering the destroyed wasteland – I imagine that most people would acknowledge that this would get pretty boring – but it’s rooted in a deep distaste for the world-as-given. The images of the world ending aren’t what you might think: this isn’t the end of the world as “the destruction of the 5.9722×1024 kilograms of rock and mineral that make up the planet earth and the thin life-giving crust around its edges”, this is the end of a “life-world” or “mental world”. And once its gone, there’s another one.

To appropriate and incorrectly use a quote from Disco Elysium: “Après la vie, la mort. Après la mort, la vie encore! Après le monde, le gris. Après le gris, le monde encore!” (“After life, death. After death, life again. After the World, the Pale (lit. “the gray”). After the Pale, the World again!”) After the world might be a period of devastation and stillness, but there will be a world beyond it.

That is, I believe, what it means to locate apocalyptic imagery in the past: to say that we have moved past it.

Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, which was Benjamin’s object of meditation for his theses on the concept of history.

Of course, there is also a darker read of things: the conception of the evils being articulated here as being not just trans-historical but as trans-temporal. They aren’t simply things that have always been there but things that can suddenly have always been there by altering the supposedly fixed events of the past. This is an invocation of Walter Benjamin’s Sixth Thesis on the Concept of History:

To articulate what is past does not mean to recognize “how it really was.” It means to take control of a memory, as it flashes in a moment of danger. For historical materialism it is a question of holding fast to a picture of the past, just as if it had unexpectedly thrust itself, in a moment of danger, on the historical subject. The danger threatens the stock of tradition as much as its recipients. For both it is one and the same: handing itself over as the tool of the ruling classes. In every epoch, the attempt must be made to deliver tradition anew from the conformism which is on the point of overwhelming it. For the Messiah arrives not merely as the Redeemer; he also arrives as the vanquisher of the Anti-Christ. The only writer of history with the gift of setting alight the sparks of hope in the past, is the one who is convinced of this: that not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious. (emphasis added)

But I don’t think it makes sense to “pick” one of these two interpretations as “correct”. Much as I tell my students not to look for “right answers” but to focus on what it asks of you – to think about the lingering questions that a work of art doesn’t settle on a conclusion to.

So, if these are the horns of the dilemma, what head do they spring from? And upon that head, is there a crown? What value can found between these extremes?

※

That’s all for now. You can follow Edgar and Cameron on Bluesky, or Broken Hands on Facebook and Tumblr. If you’re interested in picking up the books we review, we recommend doing so through bookshop.org, as it supports small bookshops throughout the US.