The Nostalgic, The Uncanny, and The Unheimlich: On ''Over the Garden Wall.'

Sigmund Freud, photographed for LIFE magazine.

There's something I've been leaving aside in all of this discussion of nostalgia, which bears mentioning, and that is the relationship between nostalgia and the uncanny (or unheimlich, to borrow from Freud.) On the surface, the most obvious comparison is on the level of the word; as Edgar noted nostalgia refers to the “sickness” or “pain” of homecoming – the melancholy feeling that wells up on witnessing something that you have lost from a distance. The German Unheimlich, on the other hand is “not-home-like”, and the English Uncanny is derived from the Scots word “canny”, which is a word that ultimately means “known”, so if we accept that unheimlich and uncanny are referring to the same thing, we have a complex of the not-(like home/known). It is often used in the sense of an “uncanny resemblance” – of something once lost now not so much recovered as thrust toward you.

Despite what I said a while back about History and Nostalgia being opposites (and, don't get me wrong, I largely stand by that) it may be more appropriate to say that nostalgia and the uncanny are entangled antitheses: the former a longing for the past, and the latter an unwelcome intrusion of the past into the present.

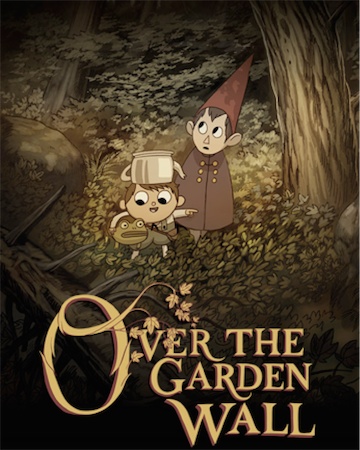

Poster for Over the Garden Wall, featuring (L-R) the Frog, Greg, and Wirt.

If Stranger Things is the apotheosis of nostalgia in television, then I submit that the avatar of the uncanny is the animated miniseries Over the Garden Wall. This series ran from the third to the seventh of november in 2014 on Cartoon Network, and followed two brothers as they attempt to make their way home after getting lost in the woods. The themes of the series are laid out in the haunting introductory melody to the first episode, the first stanza of which is “Led through the mist / By the milk-light of moon / All that was lost is revealed.” The imagery of the series is archaic, echoing what I once referred to as “fireside americana”.

This is the story of two modern youths – one adolescent and one a child – who are thrust into a place that echoes the forms and shapes of a time that, to them, is the deep past. It's archaic, but it isn't a return to home: for them, homecoming means returning to their ambiguously late-20th-century hometown. This is a haunting intrusion of alien logic into their perceptions, placing them in a world where they have to travel at various times by cart, horseback, and steamboat; where they happen upon a town of animate skeletons in the midst of a harvest celebration; where they have to escape the machinations of a monster that is more an elemental representation of the dark forest than anything else.

Perhaps it says something about me, but I often find the second episode of a series more indicative about the themes and ideas of a series. The pilot is trying to convince you and make a thesis statement, while the second episode is the first “normal” episode. In Over the Garden Wall, that episode is called “Hard Times at the Huskin' Bee”, where the brothers are joined by a talking bluebird (Beatrice, who is obviously a person turned into a bluebird, and revealed to be so in a few episodes. There is a dense substrate of Germanic fairy tales, and this isn’t treated as a dramatic revelation,) and attempt to get help from a small farm town, Pottsfield, which is in the midst of a harvest festival. The townsfolk are revealed to be animate skeletons, dead people who were dug up by the other skeletons. The leader of this town is a cat who lives inside an animated Maypole. The episode is simply drenched in a gentle variety of death-imagery. The autumnal imagery, and the juxtaposition of the townsfolk dancing around a maypole (part of a traditional may-day celebration) brings to mind Tom Robbins's throwaway line in Still Life With Woodpecker – a book where every throwaway line is an absolute linguistic grenade – that “autumn is the springtime of death.” This is an encounter that indicates something might be amiss, as Wirt tries to ask around this town that wouldn't be out of place in the early 19th century to try to find a phone (commented upon in this wonderful piece from the Film School Rejects.)

The Pumpkin-People of Pottsfield, celebrating the harvest with a maypole, transposing the vernal into the autumnal.

This might just be an instance of cartoon logic, but as time goes on it becomes clear that the two brothers – Wirt (the elder brother) and Greg (the younger) – are not from the same world as those they meet. It isn't until late in the series that their strange clothing is revealed to be Halloween costumes that they have been wearing the whole time, having met with some other young people in a grave yard, only to be scared off by the police, climbing a wall, tumbling down a hill, nearly being hit by a train, and then falling into a river. The sound of the (anachronistic) steam train even forms a portion of the closing song of each episode. However, this means that the Unknown – the forest landscape they find themselves in – isn't simply an uncanny anachronism to them. They are uncanny visitors to everyone that they meet, bewildering and confusing them as they wonder through and ask to borrow a phone to call for a ride home.

Eventually, they succumb to despair, never really understanding the nature of their problem. This despair is associated with the character called “the Beast”, who casts a shadow over the whole series, from the very first episode.

The Beast, as seen in the last episode of the series. Other than one shot, he is always seen in complete darkness, and the obscurity lends to the ominous air he brings with him to a scene.

The Beast itself is of especial importance. While much of the series is built on fairy tale logic, the Beast (and the woodsman he is associated with) is very much a satan-figure, but one derived from the fears of early colonial America and ultimately the deep forests of Northern Europe. While nearly powerless on his own, the Beast is suggested to have tricked a long line of people into feeding him – he transforms those lost in the forest of the Unknown into “edelwood trees” that can then be processed into oil, and used to feed a lantern that holds the Beast's soul. The task of feeding this lantern is given to the woodsman (voiced, unexpectedly and delightfully, by Christopher Lloyd), who believes that it holds the soul of his dead daughter.

In this way, the Beast creates a vicious cycle of shock and trauma: at the end of the series, he offers to put Greg's soul into the lantern, so that Wirt can take the woodsman's role. Realizing what's happening, Wirt stops and threatens to extinguish the lantern's flame, causing the Beast to retreat.

Admittedly, I’m prepared to see a connection to the Ambrose Bierce story — it is also the foundation of one of my favorite horror movies.

It is only after this that the two wake up, having been unconscious and on the edge of death the whole time – furthering the Americana angle by referencing Ambrose Bierce's “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”. But this explains, without words, the nature of the series. Wirt and Greg were sliding into the past, through the metaphorical “mist.” Within the narrative, this is shown by Wirt and Greg being subjected to images drawn from the collective nostalgia of the american psyche: maypole dances; untamed wilderness complete with wild turkeys; steamboats traveling down the river at a stately pace; one room schoolhouses; women wearing bonnets and working on homesteads; mansions with Georgian and Rococo architecture and decoration.

But this isn't nostalgia that Wirt and Greg have been inducted into. This is nostalgia devoid of all context, a hollow shell that they can recognize as “old-timey”, but which isn't meaningful to them. It is Trow’s question, shorn of everything to hold it back: “who is this man to you?” — “What are these images to you?” and most importantly, an answer is something that could hold the question back. Thus unencumbered, the past becomes a foreign country: a context with no legible content. All of this nostalgic imagery is milked for horror more effectively than supposed nostalgic horror media like It or Stranger Things: while understanding and effective action is reached in those projects, the Beast is not vanquished in Over the Garden Wall – it is shown to be more a parasite than a predator, and not able to be vanquished in the same way a Demogorgon or Pennywise could. But the Beast is not the only danger: and the other ones that the two boys encounter in their journey are just as alien and nonsensical.

Without a shared context, nostalgia becomes an exercise in the weird, an intrusion of that which should not be present. In that case it isn't legible to the person exposed to it, and can be experienced as an intrusion of the strange. It becomes, in short, something uncanny: you recognize that you're seeing something intertextual that has been ripped from its context.

This may be the best alternative to the nostalgic tendency: to use the momentum already present to take nostalgia beyond the point of tolerance, to break through the hazy mist of wistful longing and discomfort your audience. While comfort isn't bad, I don't think that artists should aim for it too much, because we live in a time where complacency can be fatal.

Billy Porter arriving at the 2019 Met Gala, the theme of which was “Camp.” Porter seems to be the only male attendee that understood the theme. (Dimitrios KambourisGetty Images, taken from Cosmopolitan.)

In this way, the uncanny or unheimlich (which I'm growing somewhat less convinced in the same thing) shares something with the aesthetic quality of “camp” – there's an emphasis on artificiality and intensity, a kind of ironic replication of the normal (in addition to the canonical essay on the subject, one of the best summaries of the nature of camp I heard was the comparison that Drag performances and professional wrestling are examples of camp intensifications of gender performance. Ergo, Ru Paul and Macho Man Randy Savage are both examples of camp, just with different performance as the object.)

But where camp seems, to my somewhat pedestrian understanding, to be a species or wavelength of satire, the uncanny and unhemlich are something else. They might be the conjoined twins to which camp is the unconjoined triplet, very similar, but matched to horror whereas camp is connected to satire. The uncanny, at least, hinge upon a sort of infra-perceptive flaw in the artificial performance, whereas camp relies on the flaws of the imitation being honestly out in the open. The amplification and the artificiality is the point, whereas with the uncanny and unheimlich the point is the transparent deception.

So perhaps that's it. The difference between the uncanny and the unheimlich (and here I drop the italics, because the difference has come clear): the uncanny is about a lying thing, whereas the unheimlich is about a lying context. But what is the difference between a lying context and the dawning awareness that you, yourself, are a transparently artificial thing?

So here are the question that I'm grappling with: what would an uncanny or unheimlich intensification of the 1980s be like? What would the uncanny or unheimlich intensification of our own day be?

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference.