Against Enclosure: Garrett Hardin's "The Tragedy of the Commons" is a House Built on Sand

An archetypal commons.

So, yesterday, I made the tremendous sacrifice of reading “The Tragedy of the Commons” by Garrett Hardin, so you don’t have to. I mean, you’re free to, if you really want, but I wouldn’t recommend it. I was reminded of this horrible piece of writing by an article I saw on BoingBoing, the website of Cory Doctorow.

For those not in the know, Garrett Hardin is an ecologist and biologist who wrote “The Tragedy of the Commons” (n.b.: same title, different article. This piece will be dealing principally with the prior, original article) and “Living on a Lifeboat” – a gentler version of his “Lifeboat Ethics: the Case Against Helping the Poor” (n.b.: I will not be linking to either of these.) and he’s a darling of the mainstream right and right libertarian thinking. His credentials give him an air of believably and respectability, but unfortunately a close reading of his work doesn’t support the scriptural reverence with which it is often treated. Hardin is not the canny thinker that they believe he is, and reading the original “Tragedy of the Commons” article he published in Science on 13 December 1968 shows just how flawed his reasoning is – and how bankrupt future ideological edifices built atop it are.

For the record: this man was a monster, and you will find no defenses of him coming out of my mouth.

Before I begin, an aside. As a leftist and anti-capitalist, I feel I’m held to a higher standard than my counterparts on the other side. I can’t say I think that the wage system is a bigger problem than taxes without having to say that “yes, indeed, I think the Holodomor was a crime against humanity and I don’t support it.” At the same time, fiscal conservatives won’t come out and say that putting children in cages is bad. Makes you think.

Now, as mentioned, I took the time to read through all of the original Science article – all 13 pages of it – and I came away from it not knowing how anyone could be on board with the programs he is implying. In the much, much shorter article that Hardin wrote for public consumption by the same title (get your shit together, Garrett, don’t reuse titles), he cuts out much of the implicitly Eugenic language, but he fundamentally makes the same neo-Malthusian argument.

In short, his argument can be boiled down to the statement that resources held in common tend to be depleted because people will seek to take more from what is freely available, eventually resulting in the resources going away and thus everyone suffering for it. This is often generalized out to saying that making the resources necessary to live freely available will result in a massive surplus of population and eventual famine.

The example put forward in the two-page fix-up is the aerial photograph showing the quality of freely available grazing land, used by a tribe of nomads as compared to that of the enclosed land of a nearby rancher:

In 1974 the general public got a graphic illustration of the “tragedy of the commons” in satellite photos of the earth. Pictures of northern Africa showed an irregular dark patch 390 square miles in area. Ground-level investigation revealed a fenced area inside of which there was plenty of grass. Outside, the ground cover had been devastated.

The explanation was simple. The fenced area was private property, subdivided into five portions. Each year the owners moved their animals to a new section. Fallow periods of four years gave the pastures time to recover from the grazing. The owners did this because they had an incentive to take care of their land. But no one owned the land outside the ranch. It was open to nomads and their herds. Though knowing nothing of Karl Marx, the herdsmen followed his famous advice of 1875: “To each according to his needs.” Their needs were uncontrolled and grew with the increase in the number of animals. But supply was governed by nature and decreased drastically during the drought of the early 1970s. The herds exceeded the natural “carrying capacity” of their environment, soil was compacted and eroded, and “weedy” plants, unfit for cattle consumption, replaced good plants. Many cattle died, and so did humans.

It is telling that Hardin cut out the first part of the Marx quote: “From each according to his abilities” – that is to say, common resources are acknowledged as requiring common effort to maintain. But, if you can only conceive of human beings as actors driven by rational self-interest, you would obviously cut out this statement, because it would seem absurd that anyone would contribute to the public good out of anything but personal interest.

Consider, then, that the nomads had been deprived of 390 square miles of grazing territory and were subject to market pressures – cattle often being used as an exchange good that allowed them to access the market. Their traditional way of life was broken by the introduction of new conditions, and pointing out that something is broken after you have broken it doesn’t mean that you were right to do so.

David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years (Melville House, 2014)

This lack of historical understanding is characteristic of much of contemporary economic thinking – as David Graeber points out in Debt: the First 5,000 Years, much of this field is founded upon a mythical ascent from savagery, as our economic system progressed first from barter then to coinage then to credit. This arc is nowhere observed by historians or anthropologists, and yet the myth persists.

There are many myths that Hardin propagates. This one is only contained implicitly. There are others that are contained explicitly, though he fails to see them as myths. For example, the myth of the “Welfare Queen”, that favorite folk devil of the right, the woman (probably a woman of color) who has child after bastard child to skim more money out of the welfare state. It should go without saying that this individual doesn’t really exist. According to New Poverties: Families in Postmodern Society, especially the chapter “The Birth of Poverty” by Dr. David Cheal, Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the University of Winnipeg:

It is sometimes suggested that there exists an underclass of chronic welfare recipients, many of whom are female sole parents, who realize that they can get more welfare benefits by having more children and who therefore increase their fertility. Assuming that this is true might help to account for the greater prevalence of large families among the poor. If this hypothesis is not correct, then we should find that families on welfare have more children than those who are not on welfare. There is some modest supporting evidence for this in the United States, but the evidence in Canada is only weak.

And before anyone says anything, this same source noted that "in practice, there is no difference in fertility patterns between blacks and whites in the United States that could account for the greater poverty of larger families" (both from pg. 93 of that book).

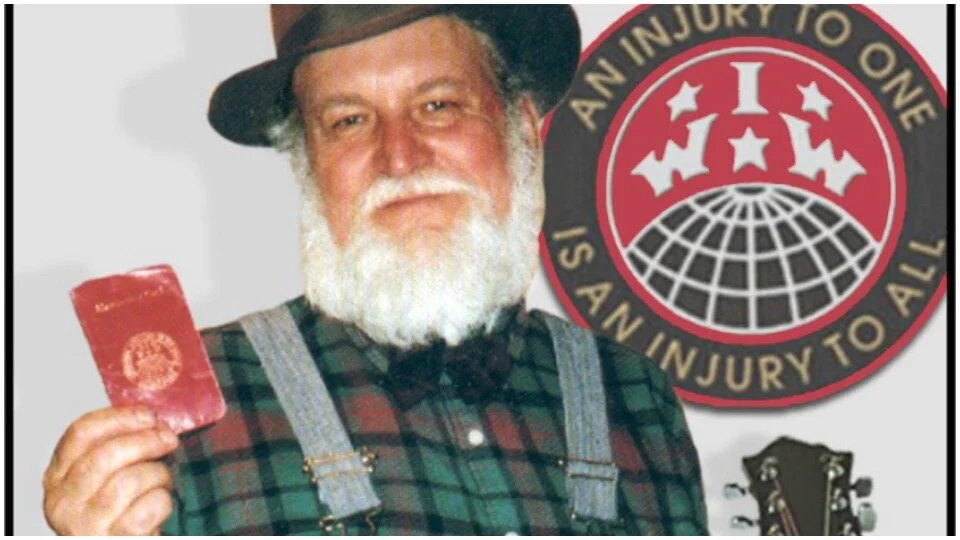

Utah Phillips, “Dump the Bosses off Your Back” — the talk before the song is the more interesting part for this discussion.

Ah, but you might say that this quote suggests that there is evidence. And yes, it does, but it states that there is variable evidence across different localities and no evidence across different races. It means that if there is an inverse connection between wealth and fertility, then it is cultural, not inherent. People choose to have children or choose not to have children for reasons beyond simply the availability of resources. These reasons fall into one of two categories – either psychological or social (and, properly speaking, economics doesn’t deserve to be a separate field and should fall under the social.) Hardin seems to think that people will have more and more children as resources become more and more available – yet doesn’t seem to measure whether the idle rich have more children than idle welfare recipients. He is, in the words of Utah Phillips, manipulating the pattern of blame, and to further paraphrase, is aiming the blame at (possibly nonexistent) little welfare chiselers at the bottom of the pecking order instead of the big chiselers up at the top of the pile. The pattern of blame is being manipulated, and Garrett Hardin is doing it right out in the open.

Thomas Malthus. This painting shows the exact moment he remembered that a poor person, somewhere, might be having sex.

When you get down to it, that’s all Malthusian concerns are, and I’m not the first person to say it (I’m not looking them up, there have been a number of pieces written about the implicit racism and sexism of Malthusian thinking.) But I find it especially telling that everyone who writes about Malthusian concerns seems to do so from a comfortable house with several children. None of them seem to think “maybe I’m part of the problem.” No, they always seem to gravitate towards the global south – and almost always towards India.

An aside. There are problems with India as a country, but we can’t overlook the fact that it’s been the punching bag of western capitalism for hundreds of years – most of Capitalism’s worst atrocities (other than the genocide of the Native Americans and the Atlantic Slave trade,) happened in India. And those are, of course, the best documented. India was a cosmopolitan, literate society before the West got involved, and Great Britain raped and pillaged it for hundreds of years in the process of extracting its wealth. The most material to our current discussion is the Bengal Famine of 1943, where there were no environmental conditions that precipitated the famine, but Britain exported almost all of the food to support the war effort.

In fact, the most extreme famines of the industrial and post-industrial periods have been not due to environmental factors, but due to market factors. We produce enough to feed the world several times over, but that doesn’t mean that workers can necessarily afford the food. During both the Irish Potato Famine and even the supposedly-communist Ukrainian Holodomor, food was exported from the site of the famine – usually cash crops. In both of these cases, for whatever reason, instead of being allowed to switch to subsistence farming, the populations in question starved while they worked land to grow crops for market or consumption elsewhere instead of for their own use.

Monk’s Mound, photographed from the air (Taken from the Guardian, photographed by Alamy). Cahokia is located in Southern Illinois, close to St. Louis.

Contrasting with this, let’s look at the Native Americans. I’m fascinated by the history of Pre-Columbian America, but I don’t want to romanticize it – there were atrocities, there was environmental devastation. The Native Americans wiped out megafauna just like the residents of the old world. However, after the collapse of the Mississippian civilization (n.b., Cahokia was bigger than London at the time that it was inhabited,) the cultures that emerged knew how to manage their environment, many of them had a robust system of commons, and none of them looked like the culture that Garrett Hardin describes.

It isn’t an issue of carrying capacity, it’s an issue of commodification, and Garrett Hardin can’t acknowledge that. The Malthusians and Neo-Malthusians can’t acknowledge that. Because they think that the problem isn’t coercion (Hardin holds up coercion as his panacea!) but that poor people — day laborers, hourly workers, and the unemployed, all together — are too stupid not to have children. Of course, the people who hold this view don’t tend to advocate for easy and free access to birth control, but seek to find ways to punish the poor for being poor, as if it is a moral failing that they need to be encouraged to overcome. It seems to me that demanding that impoverished couples not engage in consensual sex is a form of punishment (this was a feature in a novella I wrote back in 2012, called In Another Country. End shameless plug.) Of course, this is exacerbated by the fact that amenities and amusements other than sex tend to be locked behind a wall of expense – perhaps high birth rates among the poor can be chalked up to boredom.

Image from The Traveling Fool — my parents compared it to The Last Picture Show. It was the town that No Country for Old Men was filmed in, and that felt more true to the experience.

This was, at least, the vaguely-classist folk-sociological explanation I heard floated when I was in graduate school in New Mexico, in a town with one book store, two single-screen movie theaters (one of which was closed half the year, as it was a drive-in,) and only about three bars for a population of around five thousand. And this was the biggest town along a hundred-and-twenty mile stretch of highway.

There is an uncompleted study that was conducted years and years ago, commonly referred to as “Rat Park”, which suggested that social isolation and lack of amusement led to addiction. Two populations of rats were divided up. One was placed in single-occupant cages with no tools for enrichment, and two bottles of water – one drugged and one not. If memory serves, most of these rats used the drugged water, and eventually expired. The other group were placed in a complex environment with toys and tubes and a variety of foods, and with a large group of other rats. These rats also had access to drugged water and normal water. While some of them clearly tried it, nothing like a dependent behavior developed in the rats in the second enclosure.

Animal testing is a horror, but we owe a debt to the lab rat — if only because of the fact that, as William Gibson says “anything you can do to a lab rat you can do to a human being, and we can do almost anything to lab rats.”

I feel that it is criminal that this study is not more widely known – because, while it dealt particularly with addiction, it suggests interesting things about self-destructive and antisocial behaviors. Most notably, it suggests to me that a fair portion of crimes – especially those not driven by absolute necessity – are driven instead by boredom. It’s easy to think that there might be other behaviors, not only criminal behaviors, which are engaged of for the same reason, and I would imagine that even legally self-destructive behaviors come from the same source, and I would imagine that, especially for those without the resources top care for a child, having unprotected sex is a self-destructive behavior.

To make the connection explicit, it seems to me that Hardin and others who make the Malthusian argument essentialize people, assuming that behaviors like this precede the material conditions, instead of being the result of them. If you make this assumption, then some form of corrective measure on their behavior makes sense. It’s telling to me that none of them thought to test this assumption, because it seems obvious to me that they got the chain of causality exactly backwards. As a result, it seems clear to me that, if we accept the Malthusian premise that the carrying capacity of land is limited and no technical solution exists (which is, admittedly, a dodgy proposition,) that the answer is to provide social support, robust birth-control access, and open access to culture (I’m not just talking about operas for the people, or some high-brow thing like that; high-quality entertainment on public television and a well-funded public library seem like a good start.)

And, notably, unlike Hardin’s plan, my answer affords people human dignity. This is an important point: Hardin clearly had issues with the idea of human dignity.

“Mainstream Science on Intelligence” was written in support of The Bell Curve, a work of scientific racism. People who bring it up in a positive fashion have done more than buy the package that includes racism — they are espousing racist views.

Now that I feel that I have levied a sound argument against his argument for what it is (i.e., bullshit,) I want to address the aforementioned race issue. Garrett Hardin was a white nationalist. He was a nativist and argued against immigration; he was a signatory on the editorial “Mainstream Science on Intelligence” which advocated that there is a biological basis for the differences between the races, and in his final book The Ostritch Factor, argued for coercive reproductive control, preventing those who are “unfit” from breeding.

That’s right, the author of “The Tragedy of the Commons”, a scriptural text for many on the American right, a foundational text for many libertarians, their bulletproof attack on collective ownership, was written by an individual who can only be described as an eco-fascist. He snuck eugenic and eco-fascist ideas in through the back door of the American right, and warped the conversation.

A big part of this, in my opinion, is his skepticism at the thought that a group of people can make a rational choice. This is a strain in American thinking that I think needs to be addressed at some point, but I need to ruminate on it a bit before I write extensively on it, but I happen to think that this is both a myth (in the same sense as I have talked about before,) and a load of bullshit.

But almost all of this is founded in the issue of Essentialism as I have framed it in the past. In the original, 1968 piece, he wrote:

The social arrangements that produce responsibility are arrangements that create coercion, of some sort. Consider bank-robbing. The man who takes money from a bank acts as if the bank were a commons. How do we prevent such action? Certainly not by trying to control his behavior solely by a verbal appeal to his sense of responsibility. Rather than rely on propaganda we follow Frankel's lead and insist that a bank is not a commons; we seek the definite social arrangements that will keep it from becoming a commons. That we thereby infringe on the freedom of would-be robbers we neither deny nor regret.

The morality of bank-robbing is particularly easy to understand because we accept complete prohibition of this activity. We are willing to say "Thou shalt not rob banks," without providing for exceptions. But temperance also can be created by coercion. Taxing is a good coercive device. To keep downtown shoppers temperate in their use of parking space we introduce parking meters for short periods, and traffic fines for longer ones. We need not actually forbid a citizen to park as long as he wants to; we need merely make it increasingly expensive for him to do so. Not prohibition, but carefully biased options are what we offer him. A Madison Avenue man might call this persuasion; I prefer the greater candor of the word coercion.

In short, the problem for Hardin is that some people are inherently one thing or another – and yes, I’m inherently stout, but I’m not inherently a writer or a fan of science fiction or a person who enjoys curry. Some things are inherent because they are physically true. Behaviors are not inherent, because they are learned. A bank robber is not inherently a bank robber, there is a long chain of events that led them to the point where they might rob a bank.

This is a hallmark, I have seen, of a lot of right-wing thinking: they essentialize. This person is inherently a bank robber, this person is inherently a drug addict, this person is inherently a subversive (I work hard at being a subversive, dammit.) They think that these people are that way and the fact that they don’t resist their impulses is a moral failing, and should thus be coerced into behaving “properly” or punished for the same.

Essentializing is dangerous, and I’m not just saying this because I’ve been sipping on that postmodernism juice: Essentialism is the intellectual move that allows you to say “people like me are Real People, and people not like me are Not Real People.” It’s the move that allows you to say “different people have different rights.” It’s the move that allows you to say “separate but equal.” It is, in short, the wellspring of extermination – and perhaps it’s possible to be an essentialist and not make this intellectual move, but I have difficulty thinking about how you might manage to make the move without essentialization. And, I would like to stress this very, very strongly: without this line of thinking Garret Hardin’s argument falls apart, because he believes that people are automatically a particular way and cannot legitimately choose to be otherwise without coercion.

This essentializing line of thought runs all through Hardin’s piece and it shows just how intellectually bankrupt he is: everywhere, people are inherently one thing or another, and everyone – it turns out – is just Homo Economicus, the rationally self-interested value-maximizing meat-machine that would rather get beaten to death by his neighbors than back down when told to knock it off with the grazing (seriously, that’s an actual thing that he goes over in the piece. It’s wild.) In short, Hardin assumes rationality, but assumes that rationality means “like Garrett Hardin” and Garrett Hardin was an eco-fascist, so his opinion doesn’t get to count.

Nor does that of anyone who holds up “The Tragedy of the Commons” as gospel.

You know how badly you have to mess up — as an individual person — for the SPLC to have a page on you?

Christ, what an asshole!