"Sketching The Monster at Its Heart": An Appreciation of Neoreaction a Basilisk

Hello, friends! In a rare non-book roundup context, it’s Edgar, here to harangue you about, unsurprisingly, another book. But before I do, I’d like to encourage you to look into an ongoing situation here in Kansas City and perhaps help out the People’s City, and/or donate to a mutual aid group, and/or check out my own book, available here. I also recently published an article about one of my favorite mythological figures, and I’m still pretty stoked about that. And now: an appreciation of Elizabeth Sandifer’s phenomenally prescient work, Neoreaction a Basilisk: Essays On and Around the Alt-Right.

※

The cover, via Goodreads.

It feels almost quaint, at this point, to refer to “the alt-right.” In the last few years, it has become increasingly apparent that it was always composed of disparate groups with notable points of overlap, whose major virtue was that they were, and are, less inclined to eat one another alive than anything to the left of them. Many of the figures around whom the alt-right coalesced have fallen from whatever grace they may have had, too: Richard Spencer’s credit cards are exhausted; Milo Yiannopoulos lost his book deal; Steve Bannon may have finally deliquesced in Post Office custody for all I know or care. The only one of these abysmal excuses for humanity to be in the news lately is Stephen Miller, and that’s mostly because he got the ‘rona.

So why, three years afters its publication, am I still thinking on an almost daily basis about Neoreaction a Basilisk? One of the essays in the book is about Gamergate, for gods’ sake — simpler times, man! But Sandifer’s collection still rings in my mind, and not only because it is extremely quotable. It very much is, and more besides: prescient, wide-ranging, stylish, and unwavering are also words that might describe it.

But no one gives a shit about a beautiful sunset. You have to say what makes it beautiful. Some adjectives just don’t have substantial meaning, so you have to further define and refine them. So let’s shall, shall we?

※

Sandifer states, in her introduction to the book, that she intends to ask a different question than the ones many other books on the alt-right asked. When faced with the abyssal grotesquerie that formed the alt-right, she asks:

If winning is off the table, what should we do instead? Because the grim reality is that things look really fucking bad…. What then, is left?

A normal response to a rat king, pictured here in a 16th century woodcut from Wikipedia.

She doesn’t provide answers, per se, but she does adroitly and acerbically draw the shape of the problem, tracing the monstrously knotted tails of the rat king with elegance. I mean, the very first essay almost clarifies Roko’s Basilisk (except it can’t really be clarified, only believed or not, because it’s fucking ridiculous), and she moves on from there through eviscerating Nick Land, the aforementioned Gamergate essay (which has one of the most beautiful titles I’ve ever encountered), the Trump campaign and subsequent ill-starred victory, the Austrian School of economics (which even a mathematically-ruinous language guy like myself can see is hot nonsense), David Icke, TERFs, and then wraps it all up with a beautiful skewering of Peter Thiel. It’s a carnival of horrors, is what it is.

But let’s back it up a little.

※

In Sandifer’s author page at Eruditorum Press, she characterizes her approach as psychochronography, which she defines as

Taking seriously Alan Moore's notion of ideaspace, psychochronography suggests that we can wander through history and ideas just as easily as we can physical spaces, and that by observing the course of such a conceptual exploration we can discover new things about our world.

She does note, in a recent Twitter thread, that this approach is partially an outgrowth of weaponized ADHD — a method to which I am sympathetic, as is probably clear — but it is nonetheless worth exploring.

Of course, Montaigne comes to mind, as does — predictably, here at Broken Hands HQ — Mark Fisher, and those wide-ranging nerds, George Steiner and Douglas Hofstadter. Sandifer operates in a paradigm that suggests that knowledge that is available is useful to the point, and as such merits consideration. A method is, after all, a means to an end, a tool that is honeable and, in the right hands, perfect to the task. To invert an old saw, when all you have is a hammer, if you approach a problem like it’s a nail, you might make some progress.

Sandifer also treads a similar path to Eugene Thacker and Thomas Ligotti, in that Neoreaction a Basilisk approaches the truly horrific worldviews espoused by the alt-right as actual horror: a yawning vortex of madness that petrifies the onlooker. She specifically references both in the title essay, zeroing in on Ligotti as a stray thread that runs through this mess largely without becoming entangled in it. And she returns, repeatedly, to the image of the basilisk, the monstrous snake that kills with a single glance — as, of course, the brainworms willingly eaten and enabled by the alt-right will do, if you’re not careful.

He’s got a little hat! Woodcut by Ulisse Aldrovandi, via Wikipedia.

This is scarcely a new idea: the brown note, the King in Yellow, and the red pill are all species of basilisk, after all. But the image of the basilisk, rooted as it is in the misapprehensions of people like Pliny the Elder and other, later would-be chroniclers of the natural world, is especially useful to Sandifer’s project in these essays. In an attempt to understand the world as it is, teetering on the brink of environmental collapse and under a constant barrage of information, the rogues’ gallery Sandifer portrays, along with their many followers, have instead chosen death.

Brainworms it is, then.

※

As mentioned above, Sandifer takes a wide angle on the specific forms of the brainworms. “The Blind All-Seeing Eye of Gamergate,” which itself is a reworking of an earlier essay, “Blinded By the Beauty of Their Weapons” (which is the gorgeous title referred to previously) chronicles the form that gave rise to Zoe Quinn and others receiving death threats under the guise of ethics in video gaming journalism. “No Law For the Lions and Many Laws for the Oxen Is Liberty” covers the Austrian School of economics, which gave us the neoliberal hell world we now inhabit as well as the stunning failures of empathy we now see writ large, and functions as a sort of backdrop to the rest. “Lizard People, Dear Reader” examines David Icke’s well-known conspiracy theory and its anti-Semitic roots, ultimately pointing out that it, like many conspiracy theories, offers an almost comforting sense of paralysis in the face of the ultimate lack of simple answers. “My Vagina Is Haunted” covers TERFs and their vile rhetoric, which often forms a bilious flume from generally-leftish positions to the those assumed by christo-fascists and other right-wing ghouls.

Sandifer portrays these various species of violently infectious ideologies with as much an eye to flattery as Goya had, and just as much delight in the grotesque. But all this circles around what is, for me, the crown jewel of the collection, “Theses On a President.”

That essay, written just before the 2016 presidential election had been decided and reworked in light of its outcome, was my introduction to Sandifer, and remains one of the most blistering pieces of cultural commentary I’ve encountered in a long time — right up there with Jonathan Jones’ stunning review of Dismaland. I’ve shown it to many people, often accompanied by praises that almost compare in length to that of this piece so far.

The Tower, illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith for the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, via Wikipedia

In “Theses On a President,” Sandifer offers a psychogeographical reading of Trump’s campaign, with the bleeding-eyes focus of one who cannot look away, ultimately positioning the man as a willing avatar of the Tower. To quote:

He might have had a name. But then he literally built a six-hundred-and-sixty-six foot tower to which he offered up that name, sacrificing it upon its black altar such that the building became a titanic sigil of the sixteenth Major Arcana of the Tarot of the Golden Dawn, symbolizing destruction and ruin, with only the remnants of the man whose name it ate living within the rotting heart of its penthouse.

Her discussion of the outcome of the election, as fundamentally a truly disheartening referendum on the US’s attitude towards accelerationism, is no less biting. To quote further and at greater length:

Sure, his capacity for shooting himself in the foot can and will frustrate his agenda from time to time, but his agenda isn’t the only horrific thing about him. Just as ominous, if not moreso, is the corrosive effect of his very presence. This includes, obviously, the material problems of emboldened white supremacy, long-term damage to social norms, and, most importantly, the human misery inflicted by a government whose law enforcement agencies are under zero pressure towards basic humanity or decency. But it also includes the raw allostatic load of living under his rule; the basic psychological wear and tear of waking up every morning in a post-fact world dominated by a bullying narcissist. The act of living in a world where the basic validity of your identity is contingent and perpetually imperiled, where the definition of “fact” is in dispute, and where a brutish logic of dominance and humiliation pervades the entire social order.

What better way to characterize the last four years? Where so clearly on display as during the debate last week, in which three old men yelled at each other for an hour and a half as an unhappy few watched in horror? What fitter end, then, than the “Masque of the Red Death”-style farce that has followed it?

Unsurprisingly, Sandifer has some excellent takes on both of these horror-shows on her Twitter, but the extension of the symbolism laid out in “Theses On a President” is tempting enough by itself. A man already in the throes of a plague, determined to spew his bleeding, wormy guts all over the stage, now struggling to spin this into something that doesn’t end with his body decaying in the White House with maggots crawling from his eyes. What better sacrifice to the Tower?

Well, you know. We can hope.

※

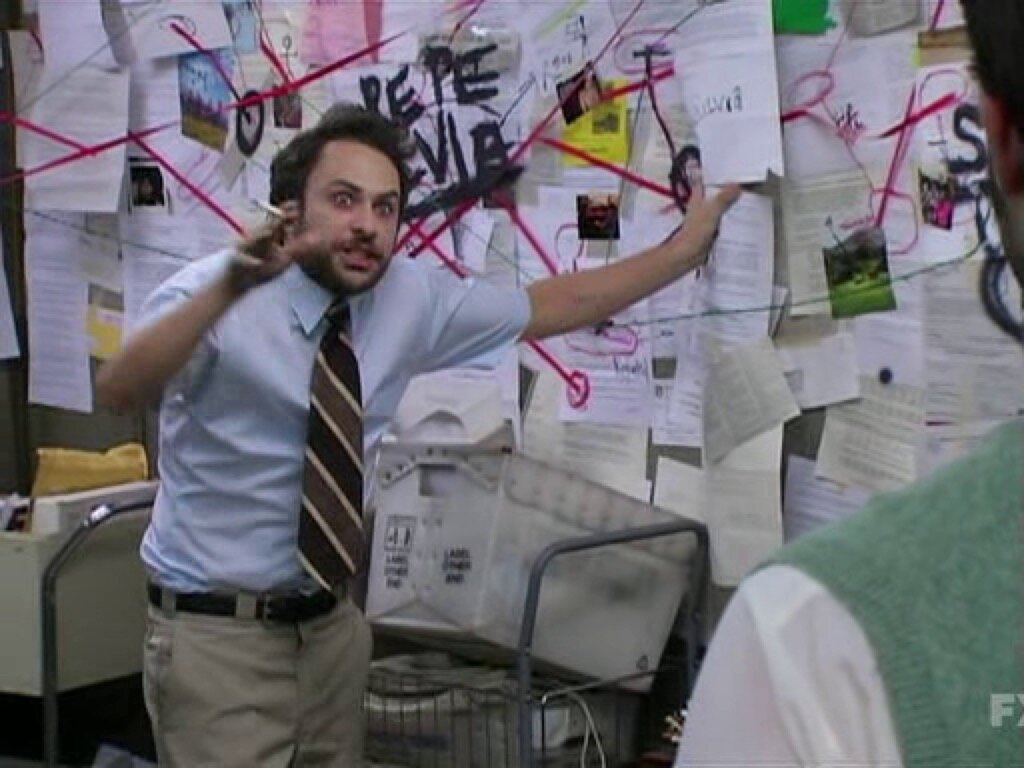

Actual footage both me writing this piece, and of trying to explain how the darkest viscera of the internet crawled out and into reality, 2010-2020; still from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia via Know Your Meme

But if, as Sandifer says in the concluding essay, “It’s been idiots all the way down,” what’s the point of writing or reading the book? For the contemporary reader, it provides a clear guide to the scope and type of the problem, like Hellier but horribly present in our day-to-day lives, disrupting public discourse at every opportunity, savagely bludgeoning any remaining hope that the internet might be at least kind of good. (And she dunks on Angela Nagle right there in the introduction, which is great.)

But I suspect Neoreaction a Basilisk is useful beyond providing sort of forensic autopsy of the hair-raisingly terrible present. What Sandifer accomplished with this book is a clear record of how things got this bad. Come with me for a moment, and consider that “the end of the world” has so far been rather less world-ending and rather more completely-society-altering, and assume that there’ll be people in a position to study history in fifty to a hundred years. In hopes that this happens, I can think of no better guide to how the pestilence that emerged from digital soil found its true home in human hearts.