The American Blindspot

The favorite phrase of the Right in America is to “pull oneself up by the bootstraps” — which is an impossibility that they would understand if any of them bothered to look at a boot. There’s no good painting of this, so here’s a related image of Baron Von Munchausen pulling himself up by his own ponytail.

I teach English Composition at the college level. It’s not the hardest job I’ve had, though there are a number of issues that I encounter fairly regularly: because I’m teaching techniques, I have to scramble to find content for my classes – you can’t write a paper if you’re not writing about something. Given, also, that it’s a university in rural Missouri, with a student population largely drawn from surrounding communities, that means that I have to filter a great deal of what I would like to make my students read: for example, I love Mark Fisher, but if I gave my students something of his to read, I fear I would swiftly be looking for a job in a grocery store.

I can tell none of them are googling the sources, because no one’s mentioned just how gay our reading list is. Edgar thinks that the reason I got pegged as a homosexual is the fact that I wash my hair, though the use of “partner” instead of “wife” might have something to do with it.

Still, I try to keep true to my ideals. I put in front of my students acknowledged great works that include writing by Malcolm X and James Baldwin – and, of course, I have students complain about how all of our readings are about how white people are evil. I chalk this up to them not following instructions about googling all of our readings to determine the time period they were written for, but it still galls me a bit.

My commitment to remaining largely a cipher, as far as my political and personal life go is necessary, but it still reveals one key thing about the way that Americans are taught. One thing that I feel explains not only a great deal of why so many well-meaning young people fail to grasp the nature of the world around them, but also why so much American political discourse is utterly useless.

Americans simply cannot do anything like a materialist analysis of current events.

Now, I’m in the process of reading Capital, though I must say I have some issues with Marxist thought (I hold closer to Murray Bookchin’s Dialectical Naturalism than Marx’s Dialectical Materialism, but even that’s not completely correct, and a conversation for another time besides.) I do think that the tools laid out in Marxist texts are fairly useful, and in the absence of something custom-made to the situation, they are the best ones we have available to us.

Some of my students wrote on healthy eating, and some others wrote on climate change. Let me give a light (FERPA-Compliant) summary of what I saw there.

The largest food desert in the country is the Navajo nation — 13 grocery stores service an area slightly larger than West Virginia. Image taken from Al-Jazeera.

One of my students writing on healthy eating was unaware of the existence of food deserts – places where there are no grocery stores, and people lack access to healthy food – and mistook correlation for causation when looking at the co-occurrence of mental health issues and obesity (obese people are often ostracized; poverty causes stress, and poverty is correlated with obesity; there is more, but again, another conversation.) It all came back to the gospel of self-responsibility and hard work.

Another of my students wrote that humanity is like a virus upon the Earth. As if every human being is culpable in the environmental destruction we see now (never mind that the Indigenous Peoples of the world – a mere 5% of the population – protect 80% of the planet’s biodiversity.) However, every cause pointed to was tied not to human beings, but to industrialism, as if we are all completely identical with our plastic entourage of electricity-sucking devices. I tried to lead the student to this, and laid out a spatial argument. To paraphrase:

I want you to imagine that you and every one of your ancestors in a direct line are walking in single file, socially distanced – one representative from each generation. Six feet behind you is your mother or father, six feet behind them is one of your grandmothers or grandfathers, and so on. This line would be a little over eleven miles long, back to your first modern human ancestor.

To reach the first of your ancestors to live in the world where the flag of the united states flew, you would have to walk back about one and a half times the length of a semi truck.

To reach the first of your ancestors to live in the world where modern English is spoken, you would have to walk a little bit less than twice that.

The first of your ancestors to live in a world with agriculture is about a mile behind you.

The causes of global warming you point to are found in the basketball court’s worth of length behind you. To say that humanity is the virus is to say that the ninety-seven or so percent of the human race that lived before that period is as responsible as the two point however many percent that lived after.

To provide a visual reference: this, but for 11 miles.

I left this comment on the rough draft but, again, the solution touted in the final draft was still personal responsibility and hard work.

That’s the American way, it seems: everyone has this myth of the rugged individualist pitched to them, they’re told that their success and failure is solely the product of their own efforts, ignoring the structural factors that contribute one direction or the other. When confronted with information that confounds the atomized narrative the response isn’t to change course – it’s to double down.

This is part and parcel of the theories of the Austrian School of Economics — an economic philosophy that was brilliantly taken down in the essay “No Law For the Lions and Many Laws for the Oxen Is Liberty” found in the book Neoreaction a Basilisk that Edgar reviewed last week.

Let’s move away from talking about my students for a bit. It’s a dodgy proposition to write so much about them, though I’m reasonably certain that I haven’t revealed anything that could identify them.

An example of this is explained in a recent episode of the TRASHFUTURE podcast, concerning the recent news that one in five companies in the US are “zombies”, their income unable to cover the yearly cost of borrowing, and sustained only by running on credit: they’re the walking dead of the financial world. This is a major problem because 2.2 million jobs are directly tied to these firms.

If you need a particular example of a zombie company, look at Uber — which has never turned a profit, but people keep throwing money at it, to the detriment of already-profitable, useful, and functional taxi companies. All it’s succeeded in doing is making a whole bunch of people 1099 workers, though California undid that.

Both the Washington Post and CNBC, the two sources linked in the prior paragraph, fail to look at this from a materialist analysis perspective: the people who run the central banks – as well as the other banks -- and the people who run these firms are all part of the same social class. The important part is not encouraging the development of newer, more efficient companies as they might claim, nor is it providing for their workers. It’s to redistribute wealth to the people who run these companies so that they continue to be wealthy (as noted in the podcast episode linked above, this suggests that every American libertarian is a failed Marxist – they view the problem as the central bank, not as the class solidarity between the banker and the business owner. This is the “crony capitalism” that they always decry but continuously recreate.)

You know. Libertarians.

Actually, wait, I have an aside about the libertarian mindset. There is a very particular failure of thinking that leads to American Libertarianism being a mindset full of unresolved contradictions – it’s an inability to think of things as extending over historical time spans: note, I’m not even saying that they ignore history (many of them do,) I’m saying that American libertarians refuse to acknowledge that historical spans of time exist. Consider: many of them feel that we need to set up a meritocratic system to reward people who perform well, but they also think that people should be able to inherit wealth. The inheritance of wealth is fundamentally an anti-meritocratic position that leads inevitably to the establishment of an aristocracy, because it leads to people receiving undeserved and unequally-distributed benefit that can be accrued over generations with very little work. It is only by refusing to acknowledge the existence of a time period measurable in years that this mindset makes any sense.

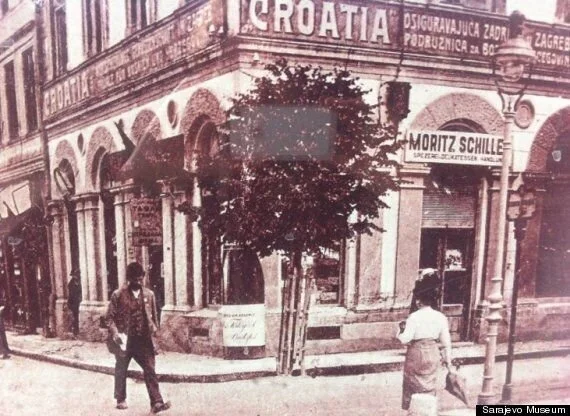

The sandwich shop was Moritz Schiller’s Delicatessen. Seen here on the right.

This is another side of it, another hole in the American conception of the world: the failure to understand that history unfolds over years and decades instead of mere months. The whole reason that we live in the world that we do is that there was a Cold War between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, which only happened after they couldn’t agree how to split up the world after they defeated Fascism, which only happened because of the crushing, shameful loss of the Central Powers in the first World War, which only happened because a Rube Goldberg machine of secret alliances meant that the whole world had to burn down because an Austrian Archduke was shot by an assassin that had missed his earlier chance and gone to get a sandwich at the exact delicatessen that Franz Ferdinand’s driver stopped in front of.

The whole world could be different if Gavrilo Princip had taken a bit longer to decide whether or not he wanted pickles – or that’s the neoliberal, individual responsibility take on the situation. The fact of the matter is that the present conditions had arisen not solely because of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand: how Ferdinand died is immaterial. The conditions for the war already existed, and like crates full of TNT, it doesn’t matter where the spark comes from so long as there’s a spark (in every meaningful way, Basil Zaharoff bears more responsibility than Gavrilo Princip, but Zaharoff was acting under the pressure of forces that were much larger than he was).

This is a tangent. We have written extensively about History and Historiography, and I invite you to read those pieces. Let me get back on track.

The problem here, the reasons that Americans don’t do Materialist Analysis, is most likely quite simple. If we were to acknowledge the fact that class exists in a very real way, we would have to acknowledge the uncomfortable realities associated with it: the fact that every winner has to come with at least one loser – or two or nine or ninety-nine. We would have to acknowledge that we’re not winners and likely never will be. Why would you want everything to be better for everyone if you could have something nicer than that by stepping on your brother’s face?

If your fate is not your own to define, then the world becomes a lot narrower and more frightening.

There is, obviously, another angle to it: no one wants to be irresponsible. As soon as you begin to say that it’s your conditions caused you to fail, the High School Guidance Counselor in your head pipes up and tells you that you need to accept responsibility — it insists that you have a moral duty to accept responsibility. We’ve all been taught that we need to accept our failures as deserved, that the most we can do is shrug and say, “What can you do?”

Never mind that some people’s ancestors had their land stolen from them, and some people’s ancestors were stolen from their land and forced to work under threat of violence, and still others are descended from those responsible for this – not to mention all the shadings and gradations between these three poles.

We recently started celebrating Indigenous People’s Day in Kansas City.

If we acknowledge the material conditions that people labor underneath, we have to decide whether we do more than just acknowledge the injustices that led to the present moment. The question becomes what we’re going to do about it.

If anything at all.

I don’t like believing my fellow Americans are a lazy, cowardly, braggadocious, and ignorant lot, but that’s exactly how we believe ourselves to be stereotyped by the world over. Which is shocking to me: my experience traveling abroad is sorely limited – and will remain as such until the various travel bans are lifted – but most people I met abroad (in France, the country typified as being the most anti-American of our allies) were actually quite complimentary.

Perhaps it’s just that: when we think of others looking at us from the outside, we think that they must believe us to be lazy, cowardly, braggadocious, and ignorant. It must be that we fear that to be what we are.

From my perspective, it seems that we fear something that might cure one of our gravest social ills, but we haven’t decided that we hate the symptoms more than we love the disease.