Truth or Fact: A Review of Paradise Killer (Odd Columns, #11)

I’m taking a short break from talking about politics to discuss a video game I completed recently, Paradise Killer by Kaizen Game Works. To an extent, this dovetails with my recent writing on mutant epistemologies.

I say this because detective fiction, after its heyday in the earliest twentieth century, does one of two things: it either simply recapitulates the tropes of hard-boiled fiction as an imitation, or it delves deeper into questions of knowledge and how we know what we know. Consider the questions of identity in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, or the exploration of Jewishness in The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, or volition in Motherless Brooklyn, or originality in Pattern Recognition, or causality itself in Foucault’s Pendulum. The question of knowledge and answers is key to the contemporary detective story. As an investigative game, and specifically as a weird investigative game, Paradise Killer discusses this, framing it in the terms of “truth or fact?” that becomes a repeated mantra.

Let me back up.

I became interested in the game due to an article I read several months ago that characterized it as a sort of mashup – one part vaporwave, one part Shin Megami Tensei (a more accurate read might have been a vaporwave version of Invisible Sun, honestly.) What I got when I played it delivered on this, but made it more complicated in the process.

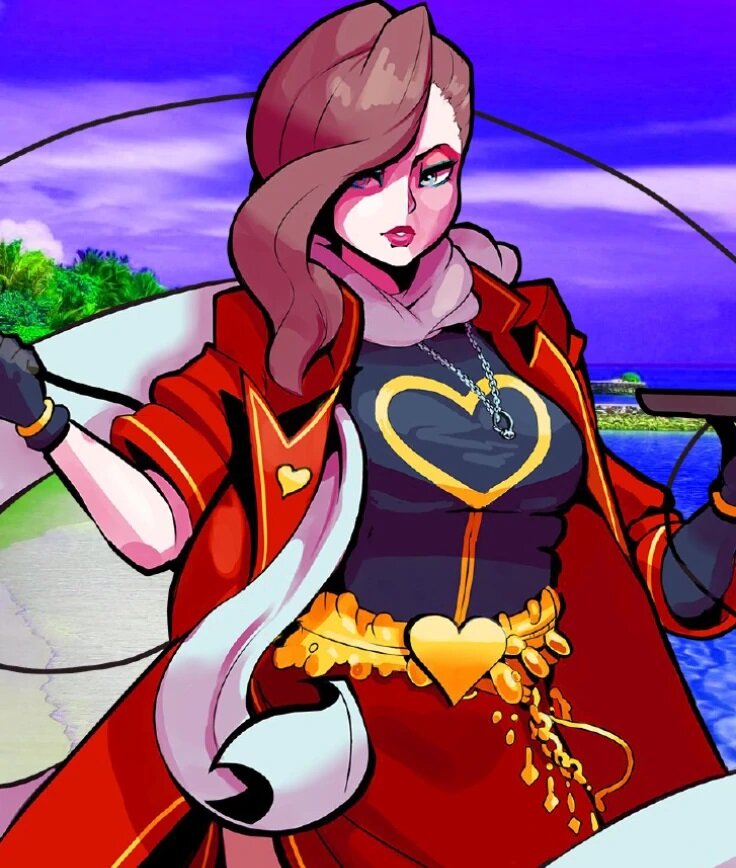

All art is taken from the game, and belongs to Kaizen Game Works unless otherwise noted.

The central character, Lady Love Dies, is called out of exile to Paradise 24 to investigate the mass murder of the ruling council of the Syndicate as Paradise 24 is being destroyed and Paradise 25 is being started – a group of people who worship dead alien gods, and attempt to resurrect them through religious ceremonies and human sacrifice. The victims for this sacrifice are normal humans abducted from the real world and brought to an alien landscape that looks like a tropical paradise but mashes up Miami and Tokyo in the way that most closely resembles a mall.

Love Dies is a former member of the syndicate, but was deceived by a god and was exiled – the exact nature of her transgression is interesting, because according to the surviving members of the syndicate she is innocent but dangerous: the transgression was on the part of the god, but she is vulnerable to it and thus needs to be quarantined.

The game mostly consists of traveling around Paradise 24 as it slowly winds down and finding evidence of several ongoing conspiracies – either to prove that the murder was committed by the one remaining normal human (a possessed young man named “Henry Division”) or by someone else. The powers that be on the island are convinced that Division is guilty, but need the results certified.

What unfolds is a complicated tale of several unrelated conspiracies colliding in an inopportune way that I will not describe (the game is under $20, and is available from Steam for even less on sale, but it’s worth it at either price.) However, there are no fights or battles to deal with, simply places to explore and people to talk to. As the game progresses, you eventually get a sense for what happened and, once you’ve finished your exploration, you can stop your wandering and begin the tribunal. At the tribunal, you run through everything, and if you can prove your assertions, it is declared by the Judge to be unarguable Fact, not simply your Truth, and it is acted upon in a bloody and final way.

The game embraces contradiction in a way that few narratives do: the Syndicate worships gods, but one of the most dangerous things for them is to listen to and be taken in by these manipulative, alien beings. They hate and fear demons, but the most helpful recurring character you can find is a demon, who provides commentary upon your progress. The next island in the Paradise Sequence will be perfect, but it has a horrible flaw built right into it. All of these contradictions are not simply present in the game, but are acknowledged and commented upon by the characters, but it’s simply allowed to happen because that’s how the world works. Possibly.

Shinji, the demon in question, is unrelated to the protagonist of Evangelion — but is notable for functioning as the closest thing the game has to a Greek Chorus. He is simultaneously located at dozens of locations all over the island, and when spoken to, offers his thoughts and then detonates with a cackle. We would all be so lucky as to bring this kind of energy to our daily interactions.

It’s exceptionally strange, especially because there is no audience surrogate character: Love Dies was part of the Syndicate (and you find out that she was also once married from a casual comment that I, at least, encountered about 70% of the way through my play through,) and already knows all about the worship of Silent Goat and the resurrection of Crying Grudge and all of the blood sacrifice (which was quite jarring to see the remains of, when I found my way to the zigguraut.) The game doesn’t hold your hand through things or really explain much, but it’s an excellent field for exploration, which is what the game is.

This might have something to do with Kaizen Game Works’s philosophy, in their words:

The core of our design philosophy is player freedom. Freedom to express themselves through the games mechanics and freedom to explore the world as they see fit.

We strongly believe that games should eschew ‘storytelling’ and embrace ‘story interacting’. Games are an interactive medium and being told a story is not interactive. Interacting with a story is something only games can do and creates an incredibly powerful player experience.

For this reason, Paradise Killer allows the player to interact with the story at all times. The player chooses where to go and when. The player chooses which evidence to collect. The player chooses how to talk to other characters and dictate the flow of conversations. The player chooses who to accuse of the murder and how to form the arguments against them.

It is up to the player how much evidence they collect, what order they do it in and who they choose to accuse of the crime. The game does not judge or ask the player to retry to get a ‘correct’ answer. The player investigates as they see fit.”

You know, Vaporwave. Image is “‘Evolution’ and Life in Vaporwave Filters” by Daniel Oliva Barbero, taken from wikimedia commons, and used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

There is also, since I’m talking about their philosophy here, the raw aesthetic of the game: it takes cues from vaporwave and related genres (which is clear in the soundtrack, I assume? I saw some reference to it being something called “city pop” but I don’t know what that is. Who do I look like, Grafton Tanner?) which means a preponderance of statues and ferns, fountains and soda machines, white beaches and bright splashes of gold, blue, and pink.

But there is an interesting emphasis on the physical presence of air conditioning machinery in the game: you can spend a fair amount of time climbing around outside apartment buildings, and there are vast banks of fan-topped air conditioners there. Somehow, in my limited contact with the genre in question, I never really gave much thought to the aesthetic weight of something as banal as air conditioning.

This is not to say that the game is perfect: I’m not sure why they bothered to include a static day/night cycle in the game, since it had no direct effect on any narrative feature, just giving a sort of excuse for a variety of artistic choices (though, consider: they could have used the angle of the sun to indicate the progress that the player has made through the mystery, with each clue found causing the sun to sink lower and lower. Perhaps this would have made it too clear what was important, however.) Also, a few of the clues presented, especially with regard to “the second lock” puzzle, were too opaque, and seemed like it should have been solvable through brute force, but the game didn’t allow this.

None of these gripes are things that made the game significantly less enjoyable for me: I liked it enough that I’m writing a little over a thousand words on it of my own volition.

It was also, generally, just an interesting narrative to explore. The handling of contradiction, which I made a lot of further up, was especially interesting to me, since most intellectual activities seem to despise contradiction a great deal – but all too often when we encounter one of the immovable, fundamental contradictions of the world we live in, we just have to kind of shrug and move on.

Crying Grudge, the one and only god that you can meet in the game, image taken from the game, via Hold to Reset.

After all, the gods may lead us into ruin and death, but we would never abandon them. Why would we do that?

After all, capital might be killing the planet, but we would never replace it. Why would we do that?

Of course, these are fundamentally different sorts of questions – the Syndicate from the game is made up of monstrous immortals harvesting the power of belief, but they at least pretend to believe in the goal that they claim to be aiming towards. This brings me to one of the things that I wish the game had given me a chance to do, which is to walk away from the situation after the mystery was solved. The golden ending – and I hope this doesn't spoil too much, because the game really is a great ride – involves Lady Love Dies returning to her former role as a kind of special investigator into deific and demonic influences, something that officially won't be a major issue.

Maybe they'll do a sequel at some point, and give that option. Who's to say? In any case, if you're looking for a way to burn a few hours, this game is highly recommended.