Against “Solving” Media

The semester is winding to a close, which means that – while I have slightly fewer direct, at-a-particular-hour, in-a-particular-place things to do – my work load is still fairly high. As such, today’s piece will probably be brief. This piece will be edging into polemic in places, and will be driven partly by the piece I wrote two weeks ago about quantitative thinking overtaking qualitative thinking, partly by the fact that I’ve gotten back into listening to the podcast Horror Vanguard, and partly by the fact that I’ve been preparing to teach a literature class for the first time.

One of the things that I’m fascinated by is the way that people engage with media. I say “engage with” instead of “consume” because I want to think beyond engagement with it as a commodity; however, I have to say “media” because I can’t simply ignore the status of stories and art as commodities in the contemporary world.

Whenever something that requires an ounce of reflection and analysis crops up, it feels like a cottage industry of YouTube videos and medium pieces and, in extreme cases, books follows, like mushrooms after a rain storm. Perhaps the one with the greatest visibility in the English-speaking internet is Twin Peaks, which led to the creation of the four-and-a-half-hour “Twin Peaks ACTUALLY EXPLAINED (No, Really)” video. I don’t know what the video says, because I’m not about to spend the better part of a day watching a video essay – especially when the cottage industry of interpretation has been churning away for thirty years and David Lynch has long resisted any amount of interpretation of his work – the author’s interpretation is, of course, not the only valid one (I can even think of a few authors where it isn’t valid) but ignoring the fact that the work is trying to actively escape a totalizing interpretation is a mistake.

A similar phenomenon happened in the Japanese-speaking internet around Neon Genesis Evangelion, written about previously on this website here. Given the tendency of the owners of this property to remix, created alternate universes and continuities, intermix it with other things, and generally treat it as a collection of ideas from which to build new expressions rather than a coherent narrative (a la Hiroki Azuma’s concept of Japanese postmodernism as a database). We have another “media property” – read “narrative” – that actively resists definitive interpretations through other means.

Similar phenomena can be found outside of television, too, mind you – it’s a short jump to John Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy (The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness), and a bit further to Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves and further still to the poetry of the surrealists.

Here’s my basic point: approaching a work of art as something to be “solved to completion” is a mistake. Thinking that you can solve it and provide a definitive analysis is a mistake. That’s the point. If it were possible to “solve” something, then you would reach the point where there was nothing in a work of art worth analyzing any more. It would be, finally and truly, dead – pinned like a butterfly beneath glass.

This does not mean that it is not worth analyzing a work of art. Quite the opposite: it means that each great work of art – in a sort of anti-canonical, “what is great and meaningful to you?” sort of way – is a veritable cornucopia of meaning. If it truly has a spark of greatness in it, then there is always more to find in there, there are always further things alchemizing and sparking into being, and all you have to do to find them is to think critically about it, and offer some of yourself to it – after all, it’s the meeting of the art and the audience that makes something beautiful happen.

Some people will argue that reading for analysis takes the joy out of what they’re reading. They think that taking it apart and analyzing how the parts work will make it so that it ceases to be a source of pleasure or wonder. I would argue that this is only true if you believe you’ve solved the whole thing: it becomes empty and dead when you decide it’s empty and dead.

Of course, the idea that you can analyze art to the point where it’s emptied of anything novel and interesting is not an idea that came from nowhere. It is born out of thinking that a novel or poem or film or painting is like a newly discovered island or a cave, and that you can map its territory and hold it in your mind. This of course, leaves aside that the territory is not the map, and even a thoroughly-mapped forest can still have new trees and new vistas to experience.

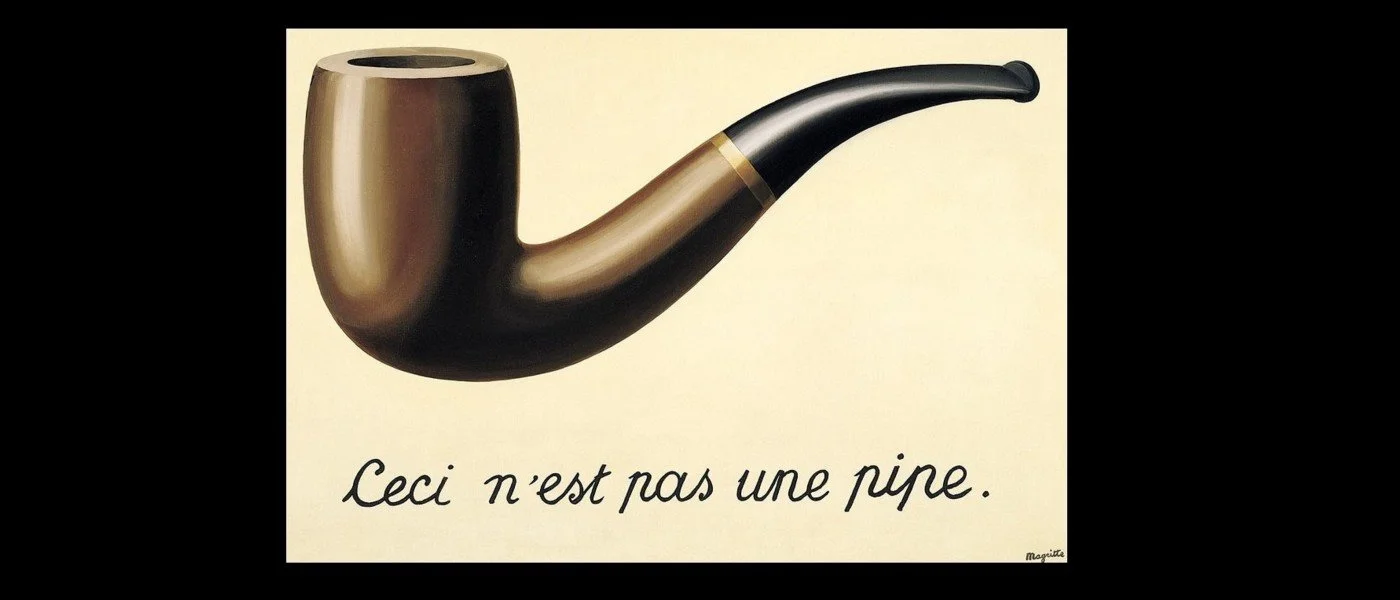

The map is, of course, not the territory, just as the painting is not the pipe. The message with Magritte’s “The Treachery of Images” is simple, but it leads to a long conversation about the relation between reality and symbol.

I connect this to quantitative thinking – the tendency of our culture to privilege that which can be counted over that which can only be experienced – because it’s a very similar tendency. You see this if you examine websites like TvTropes, a wiki into which I have sunk many hours all while wishing I wasn’t: because enumerating all of the supposed atomic structures of stories and experiences and laying them out in alphabetical order is a fundamentally different – and not necessarily useful – exercise than actually experiencing the art. It isn’t useful to count the number of dead bodies in an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie; at some point the arrangement of grains of sand becomes a pile.

The root of this, I believe, lies in the privileging of “realism” over other modes of expression in aesthetics. By this, I mean the idea that art is supposed to be a mimetic reproduction of things that would “really happen”. Leaving aside, of course, the number of really-occurring events that get you treated as insane if you acknowledge.

If you like The Great Gatsby, maybe you’d like it. Everyone in it is terrible.

That’s because realism isn’t a commitment to the truth or reality, it’s a commitment to stating that something in particular is constituent of truth or reality (see: Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism, the idea that there is no alternative to capitalism, for example). This is, of course, separate from the literary movements of “realism”, which is what most people think of when they hear the word “realism” – the idea that art should focus on depicting the prosaic and everyday (which, in turn gave rise to literary naturalism, which relates to literary realism the way that Chicago School economics relates to Classical economics, as a kind of hyper-orthodox, superlinear revolt, which suggested that there is no such thing as human agency, we’re all driven by forces larger than ourselves. I associate this movement with Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, which is perhaps the only book of fiction I dislike more than The Great Gatsby).

Treating realism not as representative of “reality” but as attempting to create reality helps explain the stance that many people take towards media these days. People treat a new Marvel movie as more essential to experience than the news – which, admittedly, is about as unpleasant as a Marvel movie but comes constantly instead of as a megadose of blue light – not just because the spectacle is entrancing, but because there are Easter Eggs hidden in it that you’re supposed to hunt for and find, which tickles the pattern-recognition neurons in your brain in such a way that you feel clever and insightful. You get that little rush of dopamine, and your brain associates the movie with that hit of feel-good chemicals.

Of course, this means that the movie is a puzzle, and it dispenses treats when you solve part of it.

Not Heck — but you can find the source of this image here.

Edgar and I have a drinking buddy who owns a very sweet, very loud, very energetic Pit Bull named “Hecate” (a.k.a. Heck), and when we go to this friend’s house, occasionally Heck needs to be distracted. Our friend will then produce a snowman-shaped plastic toy with peanut butter inside – frozen, if the friend has had the foresight to prepare. Occasionally, Heck gets distracted from this and must be reminded of the presence of her toy, called a “kong.”

It is a puzzle that dispenses treats when the dog solves part of it.

These big, tent-pole blockbusters are, essentially, human kongs.

This is not to say that other artwork doesn’t have a similar effect; when you watch Twin Peaks or read House of Leaves or look at an intricate painting, and notice an interesting connection, you get that same hit of feel-good chemical.

But when you’ve found all two hundred and eight Easter Eggs in the latest season of whatever the popular Star Wars show is now (I haven’t really engaged in a while), is there going to be anything left?

Maybe, if you keep digging, you’ll see something interesting. Maybe you’ll see a reflection of our own time, perhaps you’ll see some comment on what the writer or director thinks it means to be human. Maybe you’ll find that, and you’ll start to look for that sort of thing first, and eventually it will feel like the Easter Eggs just don’t do it anymore.

This analogy has somewhat gotten away from me, but – personally – it seems to me that analyzing what you see is going to be more interesting than trying to find all the Easter Eggs, and it seems to me that the best analysis is less about “what does it mean?” and more about “what does it say about X?”

It literally does not matter if this fictional character is a robot or not. You have no idea how many arguments have been had about this.

Consider: Who cares if Rick Deckard, Harrison Ford’s character in Blade Runner, is a replicant? How is that an interesting or useful question? I return to this one, because Blade Runner is a recurrent text in this blog and this repeatedly-asked question is one that I spent a fair amount of time assuming I had a definitive answer to – only to realize, later in life that the question was more interesting than either answer.

Questions are fertile, endlessly generating new ideas. Answers – when considered definitive – are sterile. They kill inquiry, they obstruct analysis. The only answers that should really be considered, in my mind, are those held loosely, provisionally, contingently.

Such an answer is a cuckoo’s egg, waiting to hatch and murder its nest-mates. It’s a dead end.

In short: as critics and creators, I believe that we put things absolutely backwards. We seek to untie the knots of our own questions, thinking that this will somehow lead to something important and beautiful.

The contemporary author that I believe gets this most correct is Thomas Pynchon. In his seminal early book, The Crying of Lot 49 – and spoilers here for a book from 1966 – the central character spends the whole novel searching for evidence of a postal conspiracy that may or may not exist, and finally sets things up with an auction to determine the veracity of her suspicions. When the auctioneer cries Lot 49, the truth may or may not be revealed.

The whole novel is an intricate machine of paranoia, a mystery that holds you in suspense as to whether or not Oedipa Maas is delusional or mainlining the secret history of the world. The results of the auction will determine one way or another what the world portrayed in Lot 49 is all about. Is it a novel about the mind of one person, or a world girded about with lines of conspiracy and lies? Either way, one interpretation will be rendered moot and tossed aside, shifting the story from being in both modes simultaneously to being in one mode definitively.

Pynchon ended the novel before answering the question.

Because the question is more important than the answer.

Resist the urge towards “solutions” to art.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.