Practical Libidinal Architecture (Ludo-Analysis: Part 2)

You know, practical.

In all seriousness, this first image comes from Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons prints. His work is incredibly influential on later artists of imaginary spaces, even lending his surname as the title of Susannah Clark’s Piranesi, reviewed by Edgar here.

This is a follow-up to the piece I wrote last week, and extends some of what I was saying there.

It seems to me that I managed to make some salient points about using games and play as a lens through which to read systems and events, though it is – of course – underdeveloped. It also seems to me that an analytic system that reads things in terms of a cause-effect relationship can at least be used as the beginning of a program for modifying the cause-effect relationship. This is, of course, a tricky road to go down: I wrote a few weeks back about the dangers of seeing things in terms of efficiency, and it is largely driven by that impulse.

By this, I mean that there will be a temptation to confuse the map and territory, and prize the metrics over the reality. However, it also seems to me that if you keep one eye on this fact, there’s some benefits to occasionally changing maps. It can break you out of the old headspace and allow an escape into an unexplored territory; you just have to be conscious of the fact that you will need to engage in escape again in the future, and (hopefully) you can stock your metaphorical go-bag before that’s necessary.

The key insight here is that any system that shapes human behavior through the presentation of rules and principles (explicit or implicit) can be thought of in terms of a game. My own interest lies in the use of the techniques designed for role-playing games; part of this impulse lies in the fact that a number of indie game designers refers to the basic systems that they tinker with as a kind of technology.

When my students say “technology,” they tend to mean phones and tablets – and the more historically savvy ones talk about it as a thing that began in the 1990s, as if what came before wasn’t a technology. I often make the point to them that written language, shoes, cloth, and fire are all technologies – but pointing to a predefined social practice and labeling it a “technology” gives me the feeling that my students must have when I say that the ability to start a fire falls under this same heading: the disorienting sense that the world’s axis just shifted by a degree or two, and a mixture of embarrassment and annoyance that I didn’t see it previously.

You know, technology.

But social practices are, indeed, technology.

I tend to think of this – perhaps grandiosely, perhaps unnecessarily – as a kind of libidinal architecture: creating a structure that encourages those moving through it to move towards a certain set of goals and away from a general set of lose conditions. (“Dangers” is too strong a term; I am stricken by the fact that English doesn’t seem to have a clear and exact antonym for the term “goal”; I’m already coining phrases, so perhaps I should just go all-in and label it an “anti-goal.”)

The basic idea is that the participants make moves through this libidinal architecture towards the goal and away from the anti-goal. In terms of oppositional games, you move towards your goal and away from the other player’s goal – because if they achieve it before you achieve yours, then you lose.

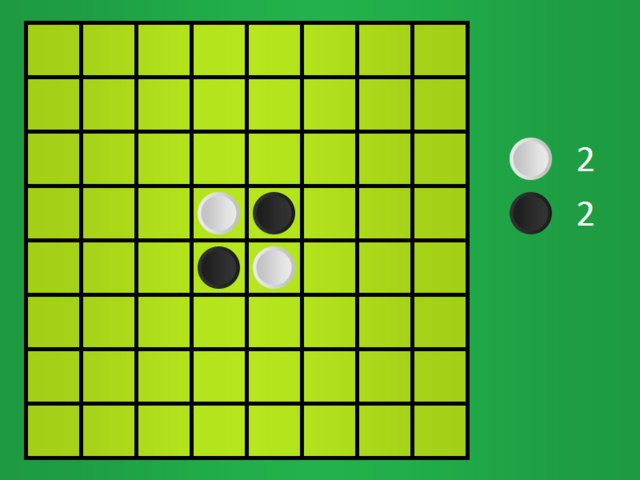

Reversi/Othello, in opening position.

All of this can be easily derived from a fairly simple game: Reversi, a basic strategy game played with 64 black-and-white tokens on an eight by eight board. The idea is that, if the white player sets down a new tile and there is a black token between an already-existing white tile and the new one, the black token is flipped over, and vice versa. The initial position of the board is pre-set (this was introduced in the version sold as “Othello,” I believe), with a four-by-four square of two black tiles and two white tiles so that each directly borders the other color and diagonally borders its matched color. In the first round, there appear to be four choices for the initial player (the one with the dark tiles) – but this is a false choice: each option is the same as all other options, just rotated ninety degrees. It introduces an asymmetry that white responds to, and it is only here that multiple options are introduced. After playing for a time, it becomes clear that the board – much like I’m given to understand with advanced chess players – becomes a simply mnemonic for the real game, which is about navigating a decision tree toward the most-optimal and away from the least-optimal position, as there are only so many available moves in each state.

Cooperative games work differently, in that all of the players possess the same goal, and share the same (set of) anti-goals. The opposition is either randomly determined, as in most cooperative board games, or (in the case of most traditional role-playing games) is determined by a player who has a different set of goals. This asymmetry often leads to that particular disease which often infects Dungeons and Dragons players of a certain vintage, where the game is treated as an oppositional one, and becomes something pursued not just at the level of the game but on meta-levels as well, where they will create dummy record sheets and seek to deceive the other people at the table.

It is the procedural complexity of chess that leads to problems such as the knight’s tour — examining if it is possible for the knight to visit every square on the board exactly once. (GIF taken from chess.com.)

Between the Goal(s) and Anti-Goal(s) lie the procedures that make up the game in question. The placement of a token in Reversi or the (visually similar, but quite distinct) Go are procedures; the movement of a Knight or Rook in Chess is a procedure; the rolling of dice in Monopoly or Dungeons and Dragons is a procedure – however, as you might notice from the fact that I italicized “Dungeons and Dragons,” there is a key difference there: I’m impelled to treat it as a type of media, because the point of the game is to generate a coherent narrative – the tactical minigames, the character creation, the skill checks, all of that is simply procedure. The goal isn’t winning, the goal is finishing the story; and so long as the players remember that this is the goal, many of them are willing to jettison and replace existing procedures as they go on: this is because it is understood that hacking the game is a procedure of the game (if one it is not optimally designed for).

In this way it resembles the game Nomic, pointed out to me by Twitter user Connor (found @BungerPatrol), this game was designed by philosophy Peter Suber and unveiled in1982 – which a game that largely consists of democratically altering the rules of the game. Notably, in the material I found on this game, there was a score but no description of how to end the game. Presumably, one would have to use the available moves to establish some kind of win-condition, if that was desirable.

Jenna Moran’s work is amazing, but it can occasionally be slightly opaque. Still, Edgar and I are going to start playing her game Glitch soon with one-time contributor Joel Gilmore, and we’re both looking forward to it.

In reading through it, I was reminded of a game I encountered in passing called Wisher, Theurgist, Fatalist, which is a Jenna Moran game and is thus extremely high-concept. In it, four players take on the three titular roles and a fourth, semi-oppositional role. Together (and occasionally alongside and in addition to playing another game) they engage in a quest of some variety. The primary mechanic is that each of the three named roles has a specific role in adjudicating some aspect of the game: how to play it, how to present it, how to interpret results, that sort of thing.

What this suggests is that including rules for the modification of procedures makes apparent the meta-game otherwise implied in the nature of the rules.

Another important consideration in tabletop RPGs, in comparison to the other games in question, is the relatively open-ended natures of the game: they can be compressed down to one session, or extended for multiple years. This is achieved by having the core procedures engaged in be treated as a loop: you go in the dungeon, you kill monsters, you get gold, you go back to town to buy new equipment and heal up; it can be modified in any number of ways, like a Baroque canon – inverted, reversed, repeated, mirrored, layered, stretched, compressed – but beyond this transformation of the basic form, the loop remains the same: far from being detrimental to the form, this allows the facilitator for the games to modify and then clothe the loop differently as the game goes on, bringing in novel elements without having to drastically redesign every session.

One might be forgiven for thinking that, between Goals/Anti-Goals and Procedures, we have a way of understanding this “libidinal architecture.” To this I would say that we lack one of the most important features: the libidinal investment. Let’s use basic terms for this and call it just “motivation.” By this, I mean the participants’ desire to participate, which is secured by one or another means. This is largely what I was discussing in my piece about the “Political Economy of Game Design” – in tabletop games, the impetus to proceed is given through the distribution of some kind of in-game currency (experience points, for example) that are roughly as meaningful as Monopoly money but are somehow even less real. This allows for that “bureaucratic pleasure of numbers getting larger” that scoring creates, but also allows for the purchasing of additional options and tools for the character to use.

This style of motivation is interesting to me because it encourages continued, long-term investment in a particular task. It becomes a feedback system, a way of allowing the participants to know their increasing proximity to the goal and increasing distance from the anti-goal(s).

While there is some disputation about whether real hydraulic societies existed in the past, there is reason to believe we might see such things in the future — Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife, which I reviewed all the way back in 2019. That was in the pre-Bookshop.org days.

I tend to think of this sort of thing as a “hydraulic” motivation (the name taken from the concept of a “hydraulic” society: control is maintained by giving or withholding a desired resource or protection from something damaging. One could look at the imposition of a debt requiring servicing to be a minimally inverted form of this: one must work to acquire the basic amount needed to service the debt, which is a sort of current drawing them towards the anti-goal. A further variant on this debt trap is the sort of madness mechanic found in some roleplaying games, which are often a sort of “death spiral” mechanic: the player is given an undesirable currency that counts up to meeting the anti-goal in response to taking certain actions – these actions might, for other reasons, be incredibly desirable, but – much like the example of reversi earlier – it becomes about managing a decision tree that wants to put you closer to the anti-goal.

Of course, this all implies the existence of one final feature, prior to all of the others: participants. No game (other than the depressive-hedonic “idle” games mentioned last week) really play themselves. There must be people involved. Some games imply a sort of hierarchy of authority within the game: in football, you have the quarterback and wide receiver; in tabletop games, you have the facilitator and you have the player (outside of Belonging Outside Belonging/No Dice No Masters/other GM-less and GM-full games; though oftentimes these games have what can be thought of as a situational hierarchy.) This hierarchy between players is often a result of having different roles: it is a system of feedback and coordination in the pursuit of a goal. Notably, outside of the aforementioned, un-facilitated tabletop roleplaying games, greater symmetry in roles between the players leads to a greater likelihood of oppositional play between the participants: the drive to win against an opponent provides the motivation.

If we think about it, the college classroom follows a similar basic architecture as a roleplaying game – it’s simply the goal that is different, and canonized in a somewhat bureaucratic fashion: the other mechanisms show a remarkable degree of similarity.

Again, Huizinga’s book.

Let’s establish, first, whether it fits Huizinga’s criteria for games:

Play is free, is in fact freedom.

Play is not "ordinary" or "real" life.

Play is distinct from "ordinary" life both as to locality and duration.

Play creates order, is order. Play demands order absolute and supreme.

Play is connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained from it.

On the first count, there are some issues with whether college is a task freely engaged-in, people technically are free to do so, though there is an immense financial barrier to entry, so on the first count, there are issues but provisionally we can say “yes.” On the second count, I have heard both students and colleagues refer to a difference between the classroom and the so-called “real world,” so we can comfortably say “yes,” here. On the third count – the “Magic Circle” quality – each class is defined as taking place in a particular classroom and being bounded in time to a particular meeting time or semester. On the fourth count, a big part of my job is establishing a set of rules and guidelines, as well as challenges, that the students attempt to abide by, so yes. Finally, we reach the questionable rule of material interest – given that it produces nothing directly and Huizinga is comfortable including gambling and contests, I think we can give a provisional “yes” here.

So, we come to the three things that I put forward: goals/anti-goals, procedures, participants, and motivation.

Each assignment has a rubric, laying out the goals, and the students are given a type of currency (points) for the completion of this. Acquiring enough of this unreal currency allows the student to pass the class (generally, in America, about 70% of the maximum amount that they are able to acquire. Notably, this entire range corresponds to the equivalent to the “A”-equivalent grade in British-derived systems, pointing out one of the major problems with international comparison of school scores.)

The “goal” is passing, the anti-goal is failing. The motivation is provided by the score, which is converted to another currency (the “grade point average”) for the larger game of college. The Procedures include “hard” or “fixed” procedures like the assignments, and successively softer or more unfixed procedures like class meetings, informal group work, office hours, and the like. Each of these procedures is meant to help push them closer to the goal of passing and the anti-goal of failing.

Ideally, using the techniques of tabletop game design, I think that it would be possible to improve the ability of these procedures to push them toward passing and away from failing without necessarily compromising the stringency of the requirements. This would ideally be achieved by changing the relationship of the student to the motivating tool and introducing new procedures that encourage a different style of engagement.

Part of the problem here is the use of a hydraulic system of motivation. It might be possible to bring in a different system – not one of the two designed above, neither debt motivation nor death-spiral motivation would be terribly fair, but there are other systems of motivation that are possible, or wrinkles to bring in that would mitigate some of the worst.

The “fail forward” mechanic is used in video games by Disco Elysium and, to a lesser extent, Citizen Sleeper. It can be implemented fairly easily with scripted interactions, but in situations that require flexibility, it can be somewhat more complicated, I will admit.

In some indie games, there is a principle of “failing forward” that seems to be something that could be interesting to explore: at a certain point in the semester, it is often the case that some students realize that there is absolutely no path forward for them – if they get an A on every subsequent assignment, they will still fall somewhere below 69.9999%. Generally speaking, at this point, the students attempt to begin to play a meta-game, requesting additional help from the professor – in short, requesting that the rules of the game be broken in their favor, in either a well-founded or purely self-serving way. This makes sense. There’s no cost to requesting special treatment: the worst thing that can happen is that the professor can say no. I see no reason to change this – I teach rhetoric as part of my class, and if a student can make a solid enough argument that they should get a C- instead of a D+, I think it behooves me to give them the time of day: after all, no assessment tool is perfect, and if they’ve learned enough to make that work, then...shit, maybe they do deserve to pass. It directly interfaces with the skills they’re supposed to be learning.

But I was discussing failing forward, back to that.

The principle of failing forward is that it should be impossible to be locked out of progression through one’s own failure. It should simply modify the course that one has to take. This does not mean that there is no cost to continuing, there certainly is, what it means is that there is no barrier to continuance placed before a student motivated to proceed. The course may be made more difficult, it may require a greater investment of time and energy on the part of the student, but it should not be closed.

Generally speaking, this requires leaving the door open for many successive attempts — and as someone who has allowed re-attempts on assignments, the results have not actually been that encouraging: it seems that allowing multiple attempts dampens either the inclination to improve or the reflection that leads to actual learning. A true fail-forward principle would require a change of state with each attempt; ideally the change of state would lead to greater learning.

Let’s see if I can come up with something for this — consider the following course of assignments.

Students are assigned to write a paper – the actual content of the paper isn’t materially important for our discussion.

I’ve had to worry about both FERPA and HIPPA (it’s medical equivalent) in the course of my professional life. I think FERPA, at least, is generally pretty good — though I wish I didn’t have to dedicate time each semester to reading out the school’s statement on it.

My current plan of attack on this is as follows: students have a first draft ready at the end of week 2 of the unit; each class day leading up to that, they read a published text in that genre. We discuss it, examine the genre and rhetorical features of the text, highlighting one or more features that makes it an example of that genre. They turn in a draft at the end of week 2, I have it graded (with feedback) at the beginning of week 3, and present an “after-action” to the class where I explain the nature of the most common missteps and how to address them. We discuss additional, less essential but no less illustrative examples in the third week, and at the end of it they have a peer review, where I assign them to work with a pre-selected group of their classmates. They revise before the peer review, and revise after it; at the end of the fourth week, they turn in their final draft.

Potentially, a fail-forward model would give them the option to stop in the second week, though I would still require evidence that they had revised. Students present two forms of the paper showing revision who score a 90+ would stop, and could focus on giving feedback to their classmates, potentially garnering additional points. Students who score 79 or below would be required to turn in an additional draft. I think this has some legs, but it unfortunately runs afoul of the Family Education Rights and Privacy (FERPA) act, in that it would give students some knowledge of how their classmates perform. Thus, while I think it might have benefits, based on my understanding of the law it is legally impossible, if only because it results in the acquisition of illegal awareness of classmates’ performance.

Let’s consider another alternative: if we prevent students from having officially-verifiable knowledge of classmate scores, then it can become more functional. We can do this by moving the finalization of scores later in the process.

So consider this: what if, in the course of the class, a series of sample papers are presented, and the students are given guidance in how to grade them – we do it as a class for the first one, and then in small groups for the second one. The third one is done individually as an online test between classes.

After everyone has done this, each student “grades” a classmate’s paper using the rubric (students can be anonymized by the used of an ID number or other means) and then writing a short, prose justification of the grading they have done. These drafts are reviewed over the course of a weekend, the student assessment is treated as an advisory element, helping to determine the score of the assessed paper, but with instructor intervention to help moderate swings in grade brought on by potentially lacking understanding.

This...doesn’t feature failing forward, but it would be a way to ensure a greater understanding of the grading process on the part of the students. I’ll give some further thought to failing forward and come back to this.

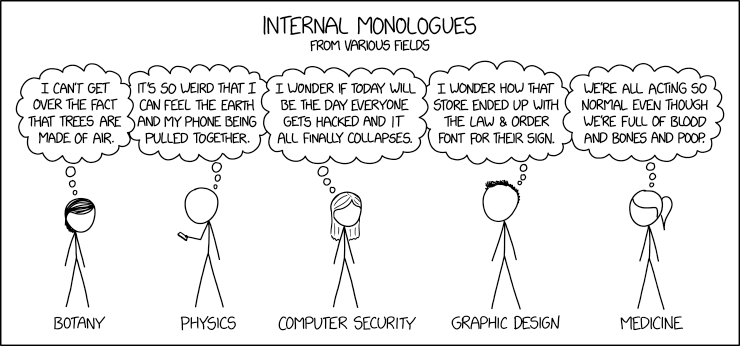

(Image taken from this XKCD strip.) Look, full disclosure: I don’t perceive myself as having an internal monologue. Sometimes I need to write things out to think through them fully.

What we do at this point, though, is where it comes in: if, after the normal procedure, students score below a certain threshold, they are required to rewrite it. If they score below a separate higher threshold, they are entitled (but not required) to rewrite it.

The issue here is that this needs to be something other than repeating the same action over and over again, which would not allow for different results. Also, for an instructor teaching four or more college classes (each of which requires three hours in the classroom and an additional [minimum] two hours of prep/grading by the instructor, and variance in this amount of time is not factored into pay scales) it might create a greater burden for the instructor that raises the input of labor beyond the financial and emotional level of reward; and, when you get down to it, my goal here is to figure out a way to raise the quality of teaching without significantly increasing the level of effort required on the part of the instructor (say efficiency without saying efficiency challenge).

Farming out the grading to the students seems a way to do this, though eventually grading will have to default back to the instructor to make sure that there is no artificial and undeserved inflation of the grades.

However, if students are allowed to try repeatedly, with additional feedback at each level, then it seems likely that a greater proportion of them will pass.

It seems likely to me that, if the first round of grading (of the rough draft) is handled by the students, this becomes more viable as a long-term strategy for increasing the acquisition of the necessary skills on the part of the student – especially if they are required to engage in reflection on the process: submitting a draft, but also marking it up with comments indicating what they changed and justifying why. This could also lessen the burden of grading for the instructor, as it would allow them to target their focus on the revisions that the student engages in.

So there are some preliminary thoughts on grading. Let’s discuss planning.

Bloom’s Taxonomy. The bit at the bottom is a Creative Commons license, and its point of origin is Vanderbilt university, but it’s too small to read without downloading the original file..

There are two primary tools that I, as a teacher, look to when planning a new assignment or class session: those are Bloom’s Taxonomy and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. The first is a simple hierarchy of tasks that proceed from least complex (recollection) to most complex (creation), while the second is a way of spatializing the acquisition of new skills, conceiving of tasks as a spectrum ranging from currently possible to currently impossible. The way to shift the balance from the latter to the former is to focus on encouraging students to engage in tasks that are slightly above their level of competency and providing guidance and encouragement in doing so – many people think of teaching as simply providing a set of facts that are then recalled and voiced.

Upon reflection, this resembles another thing that was brought into game design by the same games that taught me about the fail forward principal: the agendas and principals introduced in Vincent and Meguy Baker’s game Apocalypse World. These are a set of guidelines that are used to scaffold the facilitator’s reactions to the player’s actions.

Of course, bringing in elements of Apocalypse World is a bit questionable — there’s material in there that I wouldn’t want to discuss with students, honestly. I don’t really even use it at the table.

Building a set of “Instructor Principles” and a parallel set of “Student Principles” into the syllabus that can provide a meta-procedure for the selection of next actions seems like it could, potentially, help encourage the right kind of interactions in the classroom. Some of these may be obvious: “I will ask a question if I am confused”, “I will complete assignments by the due date”, “I will copy notes from a classmate if I am absent”, but I think that some of the less-obvious ones would be helpful, especially if they encourage students to behave in a fashion more fitting to a college student than a high school student.

In addition to this, I think that leaving a space blank on the syllabus, which presents these principles, with the instruction “write one new principle here that you intend to live up to in this class”, as well as a space in which they are encouraged to sign and date it – in a manner similar to a contract – would be beneficial. This will not, of course, have any sort of legal authority – it is a purely symbolic action. However, it is my contention that games (or game-like procedures) are largely constitutive of human society, and games are built from symbolic actions. If a student attaches an emotional value to this, then perhaps it will encourage them to follow the principles put forward.

This could perhaps be made more valuable by having procedures in place to rework the principles through a decision-making process.

These thoughts are still largely nascent, and I won’t begin designing my next round of classes for another four months at the earliest, so I’m going to cut things here.

However, it seems to me that this line of inquiry may be extremely fruitful, especially if properly researched and explored. Using, specifically, indie games like the Powered by the Apocalypse system as a guideline has the benefit of bringing in a kind of “behavioral automation”, which allows no- or low-prep running of games. If some of this social technology can be adapted for use with teaching a college classroom, it seems to me that the burden of planning, at least, can be reduced by a small measure.

If that is all that it achieves, then I think it will be a fruitful line of inquiry, though I won’t call this exploration of ideas a success unless it results in greater student engagement and higher scores (so long as this does not come with the loosening of the most essential requirements.) I will be continuing this brief series in the future, most likely alongside more writing about ludo-analysis in general, and potentially other applications of that procedure.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.