Theses on Barbenheimer

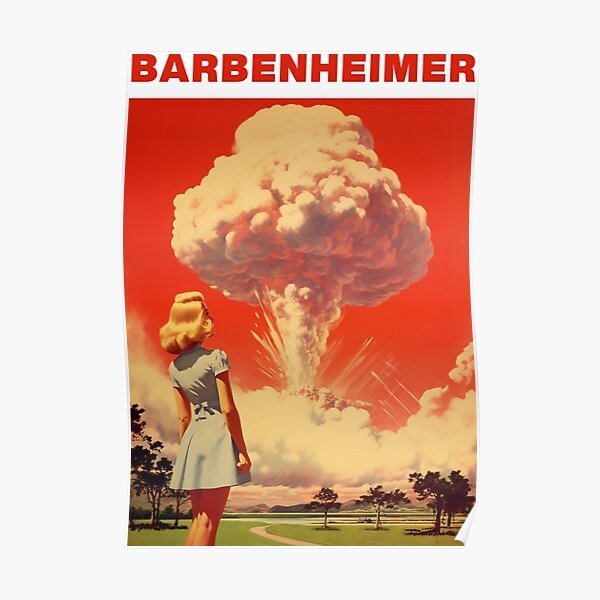

Image by Retro Travel Design.

1.

When two aesthetic objects are placed in the same context, they are in conversation with one another, regardless of the designs of the original author(s). This is the fundamental principle of curation. By moving artwork around in in space or time, new readings become possible. This is something that is obvious to someone with my education (I was an English major, and often read multiple books at the same time throughout my education), though I am sure that many other people have come to the same realization by other means.

※

It was realizing that I could move outside of nested contexts and put things next to each other in other contexts that allowed me to get the most out of my education — realizing that I could curate as well as other people who are “qualified” to do so. So I could take the bell-curve graph from my behavioral science statistics class, re-label it and use it to understand the rising and falling of retension and protension in my Phenomenology class, for example. This was part and parcel of my Jesuit education, because in the Jesuit conception of knowledge, everything is connected. This is part and parcel of Deleuzian philosophy through nomadic and rhizomatic interconnection.

※

One is a film about the yawning existential void at the heart of American life and a protagonist that crosses a line that should never be crossed. The other is Oppenheimer.

※

One is a film about a multi-talented genius that learns that some problems cannot be solved through skills, but through the strength of their relationships. The other is Barbie.

(Based on a common style of tweet the past few months.)

※

Whether through accident or spiteful scheduling, these two films are entangled. Each forms a complete text on its own, certainly. But they also come together to form a third text, an internet fever dream that speaks to the particular anxieties of our moment in a way that is not otherwise being addressed.

Let’s explore.

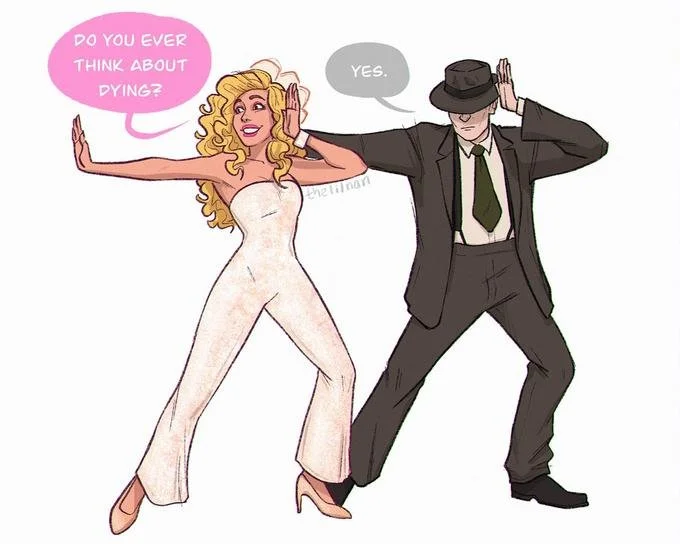

According to “Know your Meme” this comes from the Cinema Nerd Instagram.

2.

The most famous quote from J. Robert Oppenheimer is not even his. It is him, quoting a translation that he has done of a passage from the Bhagavad Gita. “Now I am become death, Destroyer of Worlds.” Some, like Professor James Madison (frequent guest on the UFO Rabbit Hole podcast, mentioned last week here, and a Professor of Philosophy at Benedictine College) view this as either a boast or a horrified realization.

It is neither of these things.

※

The context for this line is complicated. Prince Arjuna is struggling to fulfill his destiny; he’s gotten cold feet on the field of battle. Luckily, his charioteer is none other than Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu, one of the principle gods of Hinduism — I am far from a scholar of Hinduism, but I am given to understand that there is a qualitative difference between the Trimurti of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva and the various other gods that populate Hindu scriptures. For a Catholic, this would be sort of like your coworker revealing himself to be Jesus, come here to talk you through your problems — if your problems are largely a reluctance to kill a large number of people on the field of battle.

What Krishna tells Arjuna (and I don’t get this read from a professor of religious studies, but from a book I reviewed a while back called Destroyer of Worlds) is basically Krishna absolving Arjuna of responsibility.

All of these people are destined to die. You are not the cause but the means of their demise.

Arjuna is the weapon, Krishna is the will.

Oppenheimer is the means by which the bomb was built; it was not his will.

He is saying “someone else would have done it if I hadn’t.”

He also, I feel, doesn’t really believe that.

※

You can’t have a film without an apocalyptic threat anymore.

When stereotypical Barbie begins to suffer from thoughts of death, she is told that she has to go to the real world and find the child whose feelings of sadness are imprinting on her, she does so reluctantly. However, in the process, her presence is interpreted as an apocalyptic threat by the authorities, and she carries something terrible back to her world with her, threatening both worlds in the process.

Much as the fan art up above shows, Barbie is positioned as a potential destroyer of worlds.

※

Let’s talk about bones.

All of our bones are very slightly radioactive because of the fact that nuclear weapons have been detonated in our biosphere. The isotopes responsible are just sort of loose now, and it will be centuries or millennia before those are gone.

All of us, also, have microplastics in our bodies from the fact that we live in an age when plastic is just sort of there. There is no place on earth untouched by them. They are in the rain and water and air, and so they are in us.

Our world is being destroyed, twice over. Once by the gadget detonated at Trinity, and once by plastics — given an avatar in Barbie. Oppenheimer at least play-acted at guilt. How would plastics behave if given a human face and the capacity to feel?

Image taken from “Know Your Meme”, but originally drawn by Justralphy.

3.

I’ve got a series on this website called “Time of Monsters”. That draws from an Antonio Gramsci quote: “The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.” He wrote this — and also died — before the detonation of the atom bomb.

However, both Barbie and Oppenheimer are films about monstrosity. It’s obvious with Oppenheimer. A brilliant scientist unleashes a destructive force that cannot be contained. Less so with Barbie: it’s a film about a doll coming to life and then — Spoilers for Greta Gerwig’s Barbie — her companion, Ken, carrying the disease of Patriarchy back to Barbieland with him. This is explicitly compared by one character to the introduction of old world diseases to the so-called “New World.” This one line brings in post-colonial elements and conjures the specter of historical genocides — and, strangely, examines the motivations of the new oppressor in this situation through a song performed by Ryan Gosling in a giant fur coat.

※

What does it mean to put the plot of a comedy/fantasy film about a child’s toy in conversation with a historic genocide? Is this a way of introducing children to the discourse around American colonialism as much of the rest of the film does with feminist themes?

Or is it just a weird outlier, a point of comparison that the director and writers couldn’t resist making because it was so obvious? It points outside of the text, connecting it to other things.

※

Surgeons have noted that no one looks like the textbooks say when you get past the skin. Stories are like that, too. None of them completely match up to the supposed “monomyth,” and no story is complete on its own.

They all reach outside of themselves and interlace.

They all talk to history.

Knowyourmeme pointed to Sensacinemx on Instagram for this one.

4.

Of course, I’m sure you’ve noticed that I’ve mostly been reading Barbie in terms of Oppenheimer. This is largely the result of how I watched the films: starting with the dark, brooding film and proceeding to the candy-colored acid trip. This makes a certain amount of sense: eat your vegetables before having your dessert.

But it needs to be able to go both ways — neither text is subordinate to the other. What I am suggesting by my notes in Thesis 1 is that when two texts or aesthetic objects are placed in apposition (note: not opposition, but apposition) they are in dialogue with one another. This suggests that one is not subordinate to the other, but that they both become subordinate to an unseen but implied third text that we can unpack by examining the shadow upon the wall.

So, simply speaking: what does it mean to read Oppenheimer in terms of Barbie?

※

To an extent, this is a more difficult task for fairly simple reasons: everyone can easily guess what Oppenheimer is about. It’s a historical film, and with a bit of research, you can get the basic plot from a meander through Wikipedia.

On the other hand, Barbie is an original script (based, of course, on a pre-existing toy property, but you might notice that toys don’t usually have a coherent narrative attached to them.) This means that, should I attempt to not spoil it, then it becomes difficult to actually talk about it. You might notice that I’ve already done so, though it wasn’t my intention. I simply couldn’t avoid doing so.

This, of course, brings up the issue of spoilers. The focus on spoilers in popular culture is stupid, but this is hardly a new or a hot take. Consider: in literature, it’s fairly common for the end of the story to be directly given at the beginning of the story. Everyone knows that Achilles kills Hector. Everyone knows that Odysseus takes the long way home. Everyone knows that Aeneas founds Rome. This is a symptom of a variety of problems, but I think that it’s largely a shift in focus from the journey to the destination: in older literature, it was the middle of the plot that surprised and delighted the reader. Now it is the conclusion.

The story is no longer about passing through the hic sunt dracones portion of the map, and all about the production of a satisfying conclusion. This cannot be the case with historical stories (Inglorious Basterds aside), but it is the case with all other stories.

※

So let’s consider first: what would it mean to read something in terms of Barbie? What is it?

Art by Steve Reeves on Twitter (I know it says “X”. I don’t care. The URL is still Twitter.)

4.

Fundamentally, Barbie is a candy coating on a surprisingly smart examination of a number of issues. One can untangle it and find the expected feminist discourses (including in surprising places where the position of Kens in Barbieland is roughly analogous to the position of women in the real world.) But there are also issues of colonialism, queerness, and mad liberation at work.

Of course, you need to recall that this is a big studio movie based on a toy that’s been in production since the late 1950s. It’s not going to be 100% revolutionary. It’s not going to cause a complete epistemic break from what has happened previously. It is, fundamentally, a progressive or liberal project. With that in mind, it is quite good. It makes an effort to be inclusive and thoughtful and that’s all you can really ask for, as far as the vegetables go.

But it’s also very funny and well-acted, with a certain amount of joy that feels rare in contemporary movies. Despite centering on Margot Robie, Ryan Gosling, and America Ferrera, it’s an ensemble piece with an absolutely stacked cast who all seemed to be having an amazing time. The facts of its production also add to the comedy, forming a paratextual support for what’s happening on screen: the writing process involved an abstract poem based on the Apostle’s Creed and frequent viewings of the classic film musical The Red Shoes (1948) and references to Paradise Lost. It caused a worldwide shortage of pink paint. Will Ferrell is there. It’s been banned in Vietnam.

When viewed in closeup, it’s just a fun movie, a fairly successful attempt at the same kind of contemporary maximalist pop-surrealism that you find in Everything Everywhere All At Once or (in a weird, double-inverted fashion) Skinamarink. As our view pulls back, other objects enter the frame — the thematic subtext and context and paratext becomes visible.

Essentially, Barbie is impressive because Gerwig and her collaborators have managed to make a film that works on many levels, and there is a unified direction to the work that it does.

What happens to Oppenheimer when you do this?

Fanart from Twitter user @thelilnan.

5.

It breaks. There is a rigidity to Nolan’s film making that comes from his insistence on being the auteur, the promethean creator: to a certain extent, he’s been accused of including plot holes and discontinuities in his films, possibly to prove that he can maintain a monopoly on audience attention to the point where most people don’t even notice, and the majority of people don’t really care.

Oppenheimer is a masterful film, a beautiful meditation on the apocalyptic implications of the actions of one fascinating and singular historical figure. However, if viewed from anything other than the preferred vantage point (preferably in front of an Imax screen showing the 70mm cut, optimized for the particular kind of screen) it begins to warp and twist in ways that Nolan obviously didn’t intend.

Let’s talk about colonialism. New Mexico isn’t terra nullis — I lived there for two and a half years, and there are certainly people there. To this day there are still people effected by it. Likewise, it’s recently come out that something like 80% of the Visual Effects staff, many based in India, were not credited. While being denied recognition is hardly on the same level as being subjected to nuclear fallout, the decision to value one group involved in the process as lower or lesser comes from a similar place.

Sure, there are a number of things about it which are amazing technical developments, and there is an amazing amount of work that went into it — but to attribute it all to Christopher Nolan, which is the tendency with this sort of thing, is incoherent. He managed the project and brought his vision to it, but the filmic conceit that only the director has authorial control is maddening.

※

When you get down to it, the idea with Oppenheimer, as well as many other films, is that the screen should dissolve, the artifice of the theater vanish, and it is purely a monologue: the film speaks, and each atomized member of the audience is subjected to the totalized vision of the auteur.

If you perform the same zoom in - zoom out move with Oppenheimer that I talked about performing with Barbie it begins to fall apart. However, this is not to say that the movie is necessarily lacking: it is simply an incredible feat within the boundaries that we expect movies to exist within and fairly prosaic when you look at the context and the paratext. I’ll give Nolan the subtext. He can do that — but the other elements have escaped him.

※

Does this mean that Oppenheimer is bad and Barbie is good? Of course not — both are very capable films, and Oppenheimer also dips into the aforementioned well of maximalist surrealism, trying to portray the moment of realization where the title character understands the implications of what he has done and the downstream effects.

It’s just that I don’t subscribe to this reading of J. Robert Oppenheimer. While I do not think he’s a complete monster, I do feel that the film is more sympathetic to him than I am, especially in its positioning of Lewis Strauss as its villain: neither Strauss nor Oppenheimer was a particularly good person, and the conflict between them was simple political wrangling, and entirely secondary to the central drama of the film.

※

There is a problem with how people read films. Most people tend to think that the central character being followed is necessarily the hero, and that we need to sympathize with them. Ergo, whoever stands against the hero is the villain and needs to be treated as if they are evil.

This leads to a number of problems. The first is the misreading that became most apparent in reactions to the television show Breaking Bad, where people disliked the character of Skylar for interfering with her husband’s methamphetamine empire. The second is the misreading where people think that Breaking Bad lacks artistic value because it centers on objectively bad people. This is a simple example, and I am using it to discuss two common misreadings, which I feel can be transposed onto Oppenheimer.

J. Robert Oppenheimer is not a hero, he is not a villain. He was a historical personage. Lewis Strauss is the same.

But I’m supposed to read this in terms of Barbie and not in terms of Breaking Bad. How did I get this far off track?

※

Fundamentally, while I’m inclined to look at things in terms of the broader impact of the story, we can also tighten our focus down to just the protagonists and those around them. Both receive a sort of call to adventure — Barbie from the flattening of her feet, explained by “weird Barbie” (Kate McKinnon), Oppenheimer by Leslie Groves. Both then proceed to cross a line that should not be crossed: my own invocation of Prometheus is due to the fact that that Oppenheimer is explicitly compared to him; Barbie enters the real world and provokes a horrified reaction from the authorities.

Both pay a price: J. Robert Oppenheimer permanently, and Barbie temporarily (though she does leave Barbieland at the end, having decided that she wants to experience the human world. This is viewed less as exile and more as a new adventure). As such, when you get down to it, both are stories of transgressing, but there is a different orientation to the universes they take place in. Oppenheimer, as a more “gritty” or “realistic” movie is oriented towards the sin being unforgivable.

After the Trinity Test, Oppenheimer is plagued by visions of nuclear fallout befalling the people with whom he works: he goes temporarily deaf as the crowd roars triumphantly, he imagines a woman burned alive in nuclear fire, he becomes terrified of rain falling. He has sinned, and there is no going back: the world is broken.

You know what, Cillian Murphy in a sheer shirt at the Oppenheimer premier fits the vibe.

6.

However, there are also some parallels: Oppenheimer is divided into two narrative streams — the full-color “Fission” segments, and the black-and-white “Fusion” segments. The former document J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life before his loss of security clearance, and are more highly fictionalized. The latter documents, more factually, the conflict between Oppenheimer and Strauss. Perhaps we could see here a parallel between the color and the monochrome segments of this film and the heightened “Barbieland” and prosaic “real world” segments of Barbie.

Ultimately, it is the convergence of the two streams of narrative that form the crux of the story. Fission and Fusion meet, and Oppenheimer receives his punishment. Barbie crosses over and it is treated as an apocalypse. Fundamentally, these story structures imply that the world becomes strange when things are out of place.

The whole experience of Barbenheimer as a phenomenon is about this same dislocation. By reading them together, an element that was merely an adjunct to the story is elevated to a prime mover. Dislocation becomes the mechanism by which the world changes and evolves.

※

The story of Oppenheimer is not simply the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, though: it is also the story of his successor Edward Teller. After Oppenheimer invented the Atom Bomb, Teller pushed forward and created the Hydrogen Bomb. A fusion weapon, the action of which is triggered by the detonation of a fission device. Fusion follows fission.

Teller is, likewise, both a supporter of Oppenheimer and potentially the greatest threat, because he did not moderate as Oppenheimer did. He pushed further and further in the direction they were going.

In short, Edward Teller is to J. Robert Oppenheimer as Ken is to Barbie.

But what about all of the other personalities involved? Can we not see all of the Manhattan Project Scientists as being reflections of Oppenheimer, the same way that all of the other Barbies are reflections of the central Barbie? For the purposes of the film: is Enrico Fermi not just Italian Oppenheimer? Is Richard Feynman not just Chaos Oppenheimer? Is Albert Einstein not just Actually Has a Conscience Oppenheimer?

In a narrative like either of these movies, the central character is reflected in all of the other characters.

Benny Safdie does a great job, and works as a sort of stealth deuteragonist. He is Oppenheimer without the conscience.

7.

But is it enough to read each film in terms of the other? Is that actually the conversation? Or is there an additional operation that can be performed here? I feel I have already begun to gesture towards it.

To talk of Barbenheimer is to draw a circle around these two films and start a game: How are these two things alike? How can we put the one in terms of the other and use that to generate a synthesis between the two? As the memes and other artwork above show, there is a certain amount of aesthetic development that has been done on this — the mixture of desaturated black and white with super-saturated hot pink, the juxtaposition of sunny plastic and mushroom clouds.

This is a maximalist, post-modern update of an aesthetic that already existed in the 1950s.

Let’s talk about America and its derangement.

※

In the 1950s, Las Vegas celebrated its modernity by crowning four young women as beauty queens labeled “Miss Atomic”. All four of them fit the blonde ideal of American Beauty, thus marking the first libidinal crosshatching between the “blonde bombshell” and nuclear weapons, which forms the foundation of the Barbenheimer phenomenon (though, admittedly, it’s difficult to reduce the incredibly talented Margot Robie to just a visual phenomenon — she’s insanely talented).

There’s something very Freudian about the confluence of sex and death, and this phenomenon is that to a T — from one end. There is no greater death than death by atomic weapon. It’s a total annihilation. However, the sex element is incredibly personal: every culture has different ideas about sex, and every person has different preferences about it. For some reason, the juxtaposition of the traditionally attractive bomb makes far more sense than reading any other figure in here. Perhaps it’s just me, but I’m not sure that one could read a rubenesque miss atomic as being legible, to the same degree that imagining a male figure — whether we’re talking about a bear, a body builder, or a more spritely man — garbed in a similar way. The combination of sex and nuclear holocaust is purely an artifact of the post-war male psyche (though we cannot say this is purely an American derangement; there is a Russian “Miss Atom” contest that started up in 2004).

In short, a big part of this might be the fact that we accidentally recreated an archetypal figure from about 70 years ago, completely shorn of context, and now are trying to figure out what to do with her shadow. Of course, another big part might be that it’s just funny for some reason.

Perhaps it’s no deeper than that.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.