Edgar's Book Round-Up, July 2023

We’re still going monthly, lads. If anything, my commitment to reading was stronger because of how difficult one of the hottest months on record ever was. Anyway, here’s books. Links go to Bookshop.

※

The cover of Bullshit Jobs.

I lead off the month with a fun little romp through David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs: a Theory, which is a fix-up of a brief thesis statement that rocked the disaffected internet of the 2010s. Following the success of the original article, Graeber conducted some qualitative research — which is to say, solicited feedback on the bullshitness of people’s jobs — and used the results of a YouGov poll to build out the book. Which sounds unpromising, but this is a David Graeber we’re talking about here at David Graeber Fan Club Broken Hands Media, and it’s less about the facts, figures, and self-reports and much more about what bullshit jobs and the bullshittification of not-necessarily-bullshit jobs are doing to us as individuals and as a society. It was a great read, honestly, but again, Graeber generally is. I especially enjoyed his very kind dismantling of Douglas Adams’ quip in Hitchhikers Guide about hairdressers, but the book on the whole was very enjoyable.

I followed that with, in audiobook form, Jacqueline Holland’s The God of Endings. Holland, a product of the MFA program at my alma mater, promises in The God of Endings a new take on the vampire, sweeping across the Atlantic to the far side of Europe and back to New England, melding the main character’s travails as the headmistress of an elite preschool in the 1980s with her half-feral upbringing in the mountains of, mostly, eastern Europe, with a stop in France before her return to America. All of that sounds great on paper, but something just didn’t land for me. Maybe it’s the fact that Holland has a vampire running a preschool in Satanic Panic times and doesn’t even touch it. Maybe it’s the fact that the main character has such a flat affect that her occasional emotional outbursts felt tacked on. Maybe I just wasn’t in the mood. I thought the novel was basically good — just maybe not quite for me.

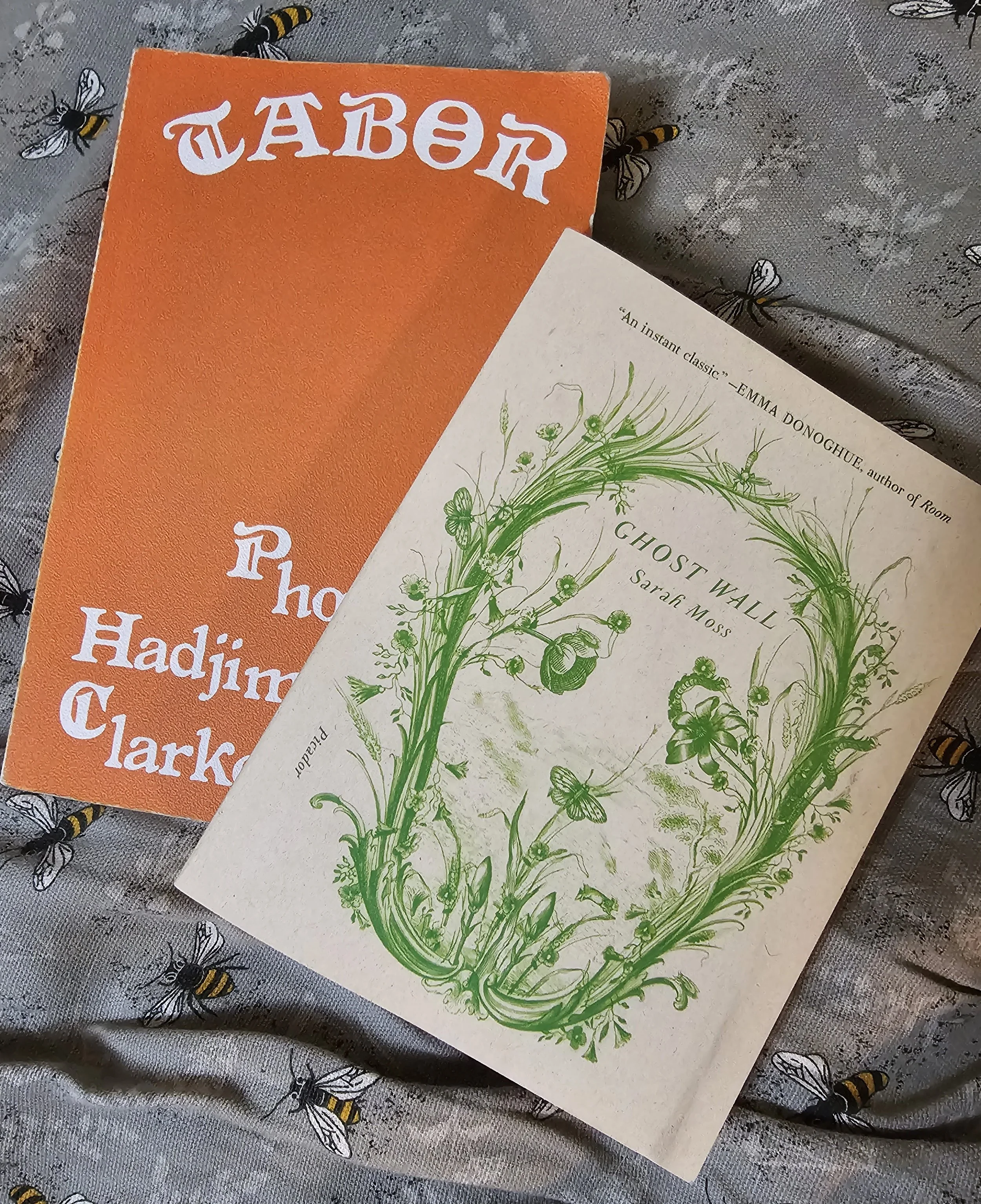

My copies of Tabor (second printing) and Ghost Wall, photographed on my couch.

It’s worth noting, too, that if I seem lukewarm on the prior two books, it’s because I read them concurrently with one that absolutely landed for me: Tabor by Phoebe Hadjimarkos Clarke (which is not available on Bookshop, so that link goes to the publisher). I had acquired it while on our travels, grabbing it on a whim because of the back copy, which claims that, “a queer prediction or a gothic reverie, [Tabor] explores the possibility of love and action in a world in ruins.” Hadjimarkos Clarke, herself a fellow-traveller of ZAD protests and a translator, gives us the story of Mona, an ascetically-inclined activist, and Pauli, an alcoholic poet, as they meet and fall in love in pre-collapse Paris; like everyone else, they’re not thinking too hard about why it’s so very warm in November until the floods come and don’t stop coming. They wash up in a nascent mountain-side community called Tabor after the catastrophic flooding, where a tacit rule forbids speaking about whatever came before — but there are still others out there, and not even the end of the world as they knew it will prevent power from consolidating itself wherever possible. All this sounds like more or less conventional climate fiction, I guess, but Hadjimarkos Clarke takes it a step further, incorporating a gestalt narration between Pauli and Mona’s sections, and in so doing, adding a layer of Medieval-flavored folk horror to the proceedings. Here’s an article in which she talks a little more about the novel. Her prose is sensuous but never overwrought, languid, sexy, and disturbing by turns. If you are reading this, and you can also read French, I cannot recommend Tabor highly enough.

To stick with the theme, I followed that with Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss, a brief, glistering novella about Sylvie, a girl on the cusp of womanhood, spending the summer with an experiential anthropology class as they seek to live like iron-age Britons. Roped into it by her domineering father, frustrated by her conflict-avoidant mother, Sylvie is fascinated by the undergraduates also on the course; her attunement to the natural world leads the other young people to view her as a bit of a savant, but as the course drags on and divisions in the group grow deeper, Sylvie will face real danger from its most common quarter: those nearest and dearest to us. Moss’ prose is lush but spare: her evocations of the beach at low tide and high noon, for example, or Sylvie’s turn to the natural world for solace in the face of her father’s abuse is extremely effective. It would have been easy, too, to render any of the characters as caricatures, but Moss never gives in, keeping her dramatis personae in sharp focus. It was great, and I hope to get my hands on more of her work.

The cover of In the Lives of Puppets, which is quite cute.

Next up, in audio form, we have In the Lives of Puppets, the new one from T. J. Klune. Longtime readers of the blog will recall my general affection for Klune’s two prior adult outings; I’ll admit, this one landed less well for me. Loosely a retelling of Pinocchio — a concept that seems to be having a moment right now — but mixed with elements of Swiss Family Robinson, we follow Victor, a human, as he and his robot buddies uncover and resuscitate another, very attractive robot that was initially constructed for the purposes of human extermination as a result of the robot uprising. This could have been a really thoughtful undertaking, but Klune never seemed to meaningfully engage with the setting he created. Neither its realities — we hear talk of batteries, but there’s also like, magic wood that reacts with human blood that will also work but has “mysterious” consequences for robots powered by it, and that’s pretty much it for power sources for a world full of robots — nor the ethical questions it implies — so many, my god, where do I even start? Free will versus design/programming is my inclination, but thinking it through for like five minutes, which I don’t have right now, would doubtless yield many more — are ever truly addressed. Nodded at in passing, maybe, but swiftly turned from, in the interests of more adorable concerns, like how attractive the robot designed as a tool for a successful genocide is, or wacky hijinx from Victor’s friends, including a Roomba that seems to be obsessed with having a penis. I don’t know, man: I will probably read more of Klune’s work, and this one had its moments — I especially liked the travelling museum of human stuff — but since the novel refused to take any but the most surface-level of its concerns seriously, I will do the same.

Next up we have Marie Brennan’s A Natural History of Dragons. This one I liked rather more, but I was raised by an anglophile, and as such I have an instinctive reaction to Tales of Adventure, of which this is a prime example. Framed as the first volume of the memoirs of in-universe noted naturalist Lady Trent, we follow the lady through his youthful fascination with dragons, aided in secret by her father, her attempts to pass as a Nice Young Lady for the purposes of marriage, and, in fairly short order, we get to the dragons and the adventuring. It’s worth noting that all of this is rankly faux-British: scarcely a surprise, knowing Brennan’s oeuvre and background, but it does color the narrative quite a bit. I am certainly curious to see if Brennan will address some of the many sins of England under Victoria to a greater extent than she does here in subsequent novels. With that lacuna acknowledged, though, it’s a fun romp, and as an audiobook, that was exactly what I was looking for.

My copies of the Steinbeck and Barthelme Arthurs, photographed on my bed.

Next up we have the first of a one-two punch of American Arthuriana, in the form of John Steinbeck’s The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights, Steinbeck’s unfinished take on Malory’s Le Mort d’Arthur. The pieces reproduced here were composed across something like ten years, and are presented here more or less in the order of composition. As Christopher Paolini notes, in his charmingly amateur introduction, the latter two stories, covering the adventures of Ewain et al., and then Lancelot, are noticeably and substantially better than the prior ones: for much of the first third of the book, Steinbeck is essentially doing a gloss on Malory, which is fine in that Malory is good, but dull in that if I wanted to read Malory, I’d read Malory. However, as mentioned, that portion of the proceedings is relatively brief, and in the last two sections, we have something closer to Steinbeck as we know him, but writing about knights instead of itinerant laborers. It’s really endearing, and the edition that I read also includes some of Steinbeck’s letters to his agent and, if I recall correctly, to his literary executor, some of which were really lovely.

I followed it with an even weirder one: Donald Barthelme’s only-slightly-posthumously-published The King, with illustrations by the great Barry Moser (which is also not on Bookshop; that’s a link to a Bookfinder ISBN search). I am less familiar with Barthelme than I ought to be — I’ve read a few stories here and there, and can only ever really remember “I Bought a Little City,” though that one is a banger and everyone should read it — and this is not something I would necessarily choose as an intro to his work. Here Barthelme is using the Arthur mythos to talk about and around World War Two, and doing so in his more or less inimitable literary style, which reads like he acquired language from mid-twentieth-century advertisements and baseball commentaries on the radio. It’s weird! It’s fun! It’s only like 150 pages, and I like that he makes fun of Ezra Pound! Moser’s illustrations are worth the time by themselves, but Barthelme is nothing if not a good time.

※

Anyway, that’s it. Follow us on Tumblr; it’s more unhinged over there.

Editor’s note, 23 August 2023: this piece has been updated to correct a factual detail. Phoebe Hadjimarkos Clarke notes that she did not live in a ZAD, but rather visited and took part in specific events.