Edgar's Book Round-Up, August 2023

We have endured! Another heat wave looms, and another fucked-up winter after that! Please help trans youth in Missouri if you can — here’s some stuff for that. Links here, as usual, go to Bookshop.

※

First up for this month, we have Peter Watts’ Blindsight, which Cameron recommended and which he discussed here. Siri Keeton, a man with a cleft brain and a preternatural ability to take in and synthesize information, is one of a crew flung out into the outer darkness to attempt first contact with an alien entity that took a snapshot of Earth and threw humanity — already not doing great — into turmoil. Siri is joined by a gang of other talented misfits, including a vampire and a cyborg doctor, but attempted contact goes sideways, and forces the characters to confront one of the ultimate questions: is consciousness really all that and a bag of chips? Watts’ prose is solid, and his willingness to engage with the psychologically unsettling and upsetting is really delightful, and his background in harder sciences definitely comes to bear in describing what, precisely, a truly alien entity might be like. It was fun, and weird, and I’ll probably read the sequel at some point when I feel more up for harder science fiction.

The cover of The Sleeping Car Porter, which I quite like, I think because there’s something very ‘90s about the illustration.

Next up, also in audiobook form, was Suzette Mayr’s The Sleeping Car Porter. Baxter, a queer Black man, has taken up work as a sleeping car porter, forced to put up with almost every indignity a man can withstand as he saves up money to go to dental school. The story unfolds over the course of a harrowing week as Baxter works a transcontinental train going from one end of Canada to the other, increasingly sleep deprived as he attempts to cater to the whims of the white travelers and not rack up so many pointless demerits that he is fired before he can earn the last $90-some dollars he needs to pay for dental school — and that’s without the mudslide that strands the train for several days. A compact, brisk, dreamlike narrative, Mayr’s research shows in the best way, in that the story feels real, but The Sleeping Car Porter also shows some of the traits of what I tend to characterize as Canadian magical realism (which I love). I’m very excited to get my hands on more of Mayr’s work.

Next up was Jazz by Toni Morrison — the first of her works that I’ve read in print. It’s difficult to describe: there’s an “I” in there, relating the story; there’s Joe Trace, his wife Violet, and the girl Joe had an affair with and then killed, whose body Violet attacked at the girl’s funeral; there’s a past to every one of them, and it binds them just as surely as their present passions do. Jazz is also the second book in a loose trilogy that begins with Beloved (which I discussed here), and I am very curious to see how Paradise, the third volume, works with that. It’s hard to know what to say about Toni Morrison because she’s probably the best American writer of the latter twentieth century, her prose elegant and poetic and demanding but never without rich reward. I only regret that I did not begin reading her writing sooner.

The hardback cover of Reverie — the paperback is kind of silly-looking but this is nice.

I followed that with Akwaeke Emezi’s Bitter, the prequel to their utopian Pet, but since I read Pet immediately after it, I’ll discuss them both together. In between, however, I finished the audiobook of Ryan La Sala’s Reverie, which was a pretty good book unfortunately encountered amidst several very good ones. And, to be quite honest, I picked it up because the top line of the blurb characterized it as “Inception meets The Magicians,” which was neither quite accurate nor quite fair. True, Kane Montgomery, the central character, is as self-obsessedly depressed as Quentin from the latter series, and true, Reverie does feature characters travelling through dreams, as in the former, but it’s doing something different — fundamentally, La Sala is using his teenaged protagonists and their attempts to save themselves, their loved ones, and their home town from a plague of dreams made real as a way to explore a number of different genres and their conventions, with interludes of teenagers having teenager problems. And taken that way, it’s a lot of fun. I enjoyed it, and I’ll probably look for more of La Sala’s work.

But to the Emezi pieces. I’ve discussed Pet here before; Bitter came out the other year and I only recently picked up a copy. Pet takes place in a more or less post-revolutionary society, following Jam, a young trans girl, as she wrestles with the question of how to deal with wrongdoing in a society in which wrongdoing is no longer believed to be possible. Bitter, meanwhile, takes place during that revolution, following Jam’s mother as she grapples with the role of art in a time of political turmoil. Although the two books are very different in their goals, they’re similar in many ways, not least of which is Emezi’s absolutely gorgeous prose. As usual, their work is excellent and I’m thrilled to be around to watch their career unfold.

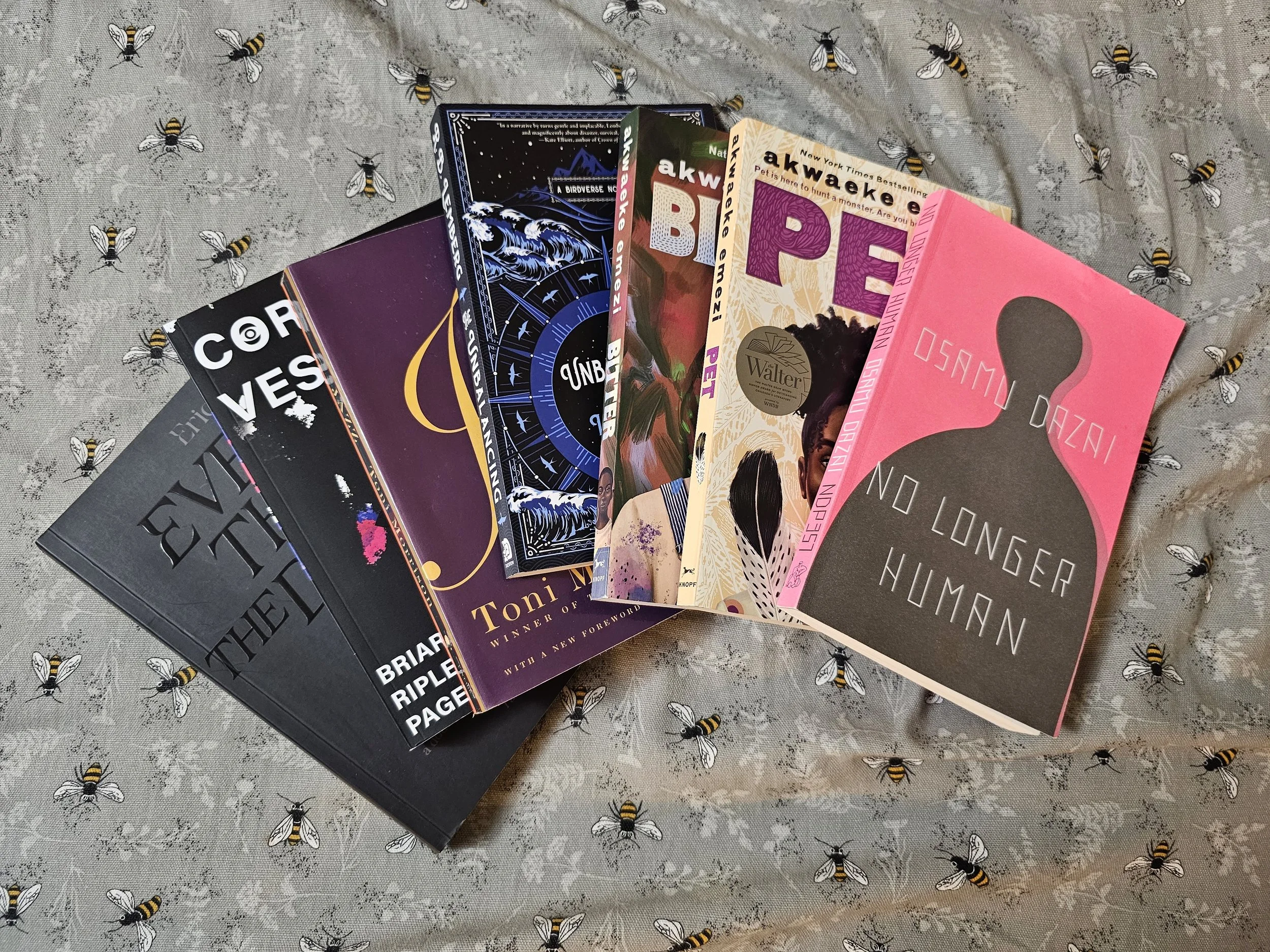

Here’s all the print books on this list, looking as nice as I can make them at 9:45pm on my couch.

Next up, also in print form, we have Everything the Darkness Eats, Eric LaRocca’s novel debut. Cameron and I both read and more or less enjoyed Things Have Gotten Worse Since Last We Spoke, LaRocca’s breakout novella; I was impressed there by LaRocca’s command of a very particular kind of early ‘00s online linguistic register, and I was curious to see how they would do at novel-length. The answer is: okay, I think? The novel follows several protagonists as they are drawn into the whims of the mysterious Heart Crowley, but the plot is secondary to the vibes. LaRocca writes here like Garth Marenghi doing a Clive Barker impression, and the results are compellingly bizarre (though I was mildly annoyed by the persistent misuse of the verb “covet”). It is worth noting that there’s an extended sexual assault scene, which I felt LaRocca handled well, but it was long and intense. And there, too, LaRocca’s weird, fever-dream prose works in their favor. It was certainly an odd one.

I next finished Corrupted Vessels by Briar Ripley Page. Page came onto my radar via the social media network formerly known as Twitter, and in preparation for a rerelease of this book, they were selling some old copies of the first edition. The novel follows River, a young trans boy under the spell of the beautiful, androgynous Ash, who believes that the two of them are incarnations of elemental angelic beings — but when Linden, a transmasculine college student, stumbles into their temporary haven, the relative peace of River and Ash’s little cult will not survive. Page’s style is spare but their vision is lush and hallucinatory, elegantly capturing the fraught, dream-like tensions of a very particular time in youth and young adulthood. From the collective house where Linden lives, to the grocery stores and dive bars of the college town where the story takes place, to the abandoned house in the woods where River and Ash have holed up, there’s a real sense of place to the story, lending it real richness and depth to counterbalance the baroque imaginings of Ash’s visions and the heady tensions between the three central characters. It’s really fucking good, is what I’m saying, and I’m excited to read more of Page’s work.

I next finished — and it’s worth noting here that for the last couple of weeks I’ve lacked the capacity to do much but sit and read — Osamu Dazai’s classic novel, No Longer Human, translated by Donald Keene. A much-lauded entry in one of my favorite genres, A Fucked-Up Guy Tells You About His Life, the protagonist of No Longer Human feels himself cast out of the realm of the human, his relations with others built entirely on fear and a tenuous construction of the self that he knows cannot withstand scrutiny. Cameron discussed this one here, and I generally share his opinion on the piece. It definitely feels Dostoevskyan to me, but I am a Dostoevsky guy, for better and for worse. You can really tell that the author was unwell when writing it, and his eventual fate does color the novel quite a bit. It’s a classic for a reason, though, and the depictions of the moment when someone sees through your charade are truly unsettling.

The cover of The Wicked Bargain — pretty normal, but gets the idea across.

Next up, in audiobook form, we have Gabe Cole Novoa’s The Wicked Bargain. The novel came to my attention as one to read if you like Our Flag Means Death, which I did and do; Novoa’s tale of a nonbinary pirate with magical powers definitely sails similar waters, to such an extent that Vico Ortiz voices the audiobook. Young Mar learns that their father had entered a deal with el Diablo when they were an infant, and on their sixteenth birthday, el Diablo comes to collect, killing the rest of Mar’s father’s pirate crew in a storm and offering Mar two months to find a way to save their father. It was a fun romp: the pacing felt a little wonky, but Novoa does an excellent job of digging into the politics of later piracy and the Caribbean. I enjoyed it thoroughly.

The US cover of The Hole — appropriately evocative

The only ebook on this list is The Hole by Hye-young Pyun, translated from Korean by Sora Kim-Russell. In the same existentialist vein as No Longer Human, The Hole gives us Oghi, formerly a successful professor of geography and public academic, now almost entirely paralyzed and disfigured by the car accident that killed his wife — and his mother-in-law rapidly becomes his sole caregiver. As her abuses of his property and his person mount, Oghi is also forced to reckon with the truth of his relationship with his wife, and how that relationship impacts his current predicament. It’s a deeply claustrophobic novel — the action rarely departs from Oghi’s bedroom, and interactions with people other than his mother-in-law grow increasingly rare as the novel progresses. It took me as long as it did more because I have been struggling with ebooks lately, and not through any fault of the novel. I will definitely be looking for more of Hye-young Pyun’s work.

The final print book in this round-up — I am in no way kidding when I say I have done very little but read recently, for various reasons — is R. B. Lemberg’s The Unbalancing, the first novel in their Birdverse setting. I quite enjoyed The Four Profound Weaves, but sometimes found its imagery opaque. I had fewer issues here, but I think that’s partially because, despite being the longer work, The Unbalancing is much more discrete in its setting and scope: we follow Ranra Kekeri, the newly-minted Starkeeper of the island of Gelle-Geu, and Erígra Lilún, a poet whose ancestor was the first Starkeeper, as they try to save the island from destruction at the hands of its guardian star, and negotiate their own burgeoning relationship. Lemberg is very much working in the LeGuin tradition, and this novel is, in a certain sense, a utopian one: the archipelago of which Gelle-Geu is a part is notably more inclusive than other settings in the Birdverse, and the subplot about Lilún’s coming to terms with their nonbinary identity was a welcome vision of what self-actualization looks like when freed from society-wide judgment. Lemberg, also a poet, offers spare, meditative prose that nonetheless paints a highly effective portrait of its setting. I really liked this one, and I’m glad to have read it.

The cover of Lost in the Moment and Found, which more or less follows the format of the others in the series.

We close this round-up with a final audiobook, Seanan McGuire’s Lost in the Moment and Found, the latest in her Wayward Children series, which Cameron and I have discussed a few times elsewhere. This one focuses on Antoinette, one of the several characters embroiled in the main plot that progresses in the odd-numbered entries in the series. I really love that element of the series’ structure, and I think it works extremely well overall — but I’ll admit, I struggled more with this one than with others in the series. Antoinette’s durance (to borrow a term from my favorite TTRPG of all time) felt somehow half-baked, and while McGuire writes extremely strong characters, here the captors of sorts seemed ill-realized. But perhaps I judge it too harshly, and let’s be honest: I will definitely be reading the next one as soon as I can.

※

That’s all, folks. I have obtained access to Bluesky, and you can follow along as I don’t post shit on there, either, or hop over to Tumblr, or follow me and Cameron on Twitter.