Eerie Theodicy: On Townes Van Zandt’s “Lungs”

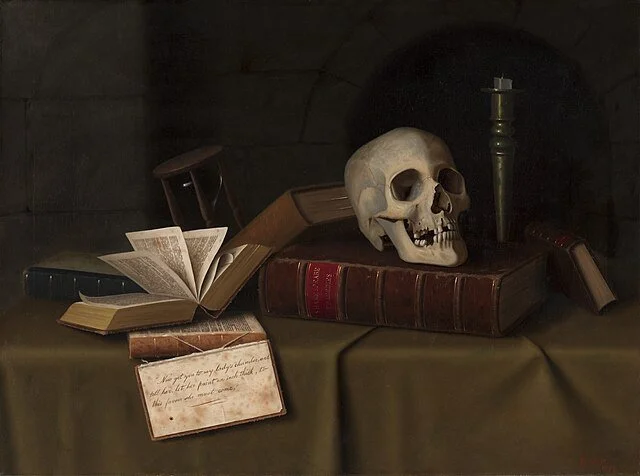

Conquering heroes in Rome often had a slave assigned to follow them and periodically remind them “memento mori” (Remember, you will die.) Remembrance of the presence of death is, consequently, a consistent theme in the arts.

I feel that the normal thing to do in the wake of loss is to think on issues of theodicy – which I’m using in its broadest sense, as the question of why bad things happen and suffering exists. In my day to day life, I tend to banish these questions: I don’t tend to think of the world as having a single source of pain and discomfort. It comes about because the world is, as much as we would hope, an imperfect place, and the experience of that imperfection is pain. For those of us with a utopian streak – and, as cynical as I can be at times, I do have one of those – this can be an endless source of sorrow and discomfort: there’s always the sense that something could have been done, and it’s occasionally helpful to acknowledge that Aurelian wisdom that some things are simply outside of the sphere of your control.

We lost a friend recently. Back when this website was primarily the host for a narrative podcast that we were putting together and not the landing pad for my pseudo-philosophical ramblings, he recorded the sheriff in our two-parter, doing and admirable job providing a cod Gordon Cole for our weird little show. Beyond that, he was a good friend and had a true genius when it came to audio engineering.

So it comes that I think on death.

※

Theodicy comes from theology but often finds itself, like many subjects, placed in the philosophy department. It comes from roots theos and dikē that ultimately come together to form a compound that means “God’s justification”. As someone who finds himself lacking traditional beliefs but who was raised Catholic, this turning of the tables is appealing to me as an intellectual exercise.

The central question goes “if God is all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good, then why is there suffering?” The traditional approach here is to problematize one of the five important terms here – it’s simple enough to answer if we assume that the interlocutor doesn’t understand what is meant by “God”, “all-powerful”, “all-knowing”, “all-good” or “suffering”.

If you remove “God”, then you have some sort of non-monotheistic system: there are more or less than one God in the universe, and so there is either conflict or no one in control. As such, the rest of the question is irrelevant.

If you complicate “all-powerful”, things become different, too: in the Catholic context, the best of these is probably Process Theology, which claims that God’s omnipotence is not coercive but persuasive. He doesn’t make anything take a particular action, he persuades events to go one direction or the other – but for this to be meaningful, it can’t be a certain thing. I have some sympathy for this position, as it was my introduction to process philosophies, which longtime readers will know I’m a fan of.

If you complicate “all-knowing” then it becomes matter of drawing God’s attention to the sources of suffering. This is, obviously, one of the less satisfying ways of squaring the circle, and you very rarely see people making this argument.

Jacques-Louis David’s “The Death of Socrates” — the Euthyphro Dilemma is articulated by Socrates is one of Plato’s dialogues, and I’d argue that a lot of Plato’s philosophy (voiced through Socrates as a mouthpiece) is connected to this dilemma.

Complicating “all-good” is a rich vein of discourse, though. Oftentimes, you see this answer simplified into the statement that God’s good isn’t necessarily your particular good: as if some more horrible fate is staved off by you stubbing your toe or getting in a fender bender. Perhaps it is, but it seems like there are other mechanisms that might be more effective. Another approach is to state that, ultimately, God is not necessarily good in the way that we think of “good” – which has some scriptural backing, and seems to be alive and well in some parts of Jewish debate on the issue after the Holocaust. The way you approach this one seems to be wrapped up in what Greek Philosophers called the “Euthyphro Dilemma” – the question of whether good actions derived that status because the gods willed them or whether the gods willed that we take good actions because they are good (or, to simplify: if you received a commandment from God saying to commit murder, would you? The former camp on this says “yes”, the latter says “no”. I know which one I’m comfortable sitting at the same table with.)

Finally, there’s complication of suffering: maybe you need to go through terrible things to become wise or otherwise improved as a human being. This is somewhat seductive as an idea, but at the same time, much of the suffering that we go through doesn’t really seem to be to anyone’s benefit, much less our own. That’s part of what makes it suffering: the feeling that it isn’t really worthwhile in any sense.

But this last one, at least can become a kind of program. An instruction for approaching the world. You’re going to suffer. That can’t really be avoided. Maybe you should at least try to pull a lesson out of it? It might not make it worthwhile, but there is a very real difference between getting kicked in the teeth on the one hand and getting kicked in the teeth but you found five dollars while you were down on the ground. It doesn’t make it good, but it’s something at least.

※

I first encountered the song “Lungs” by Townes Van Zandt about a decade ago. It’s the musical sting at the end of the seventh episode of the first season of HBO’s True Detective, a show I’ve mentioned in passing here and which Edgar and I watch annually in the spring. It seems to have little to do with the content of the scene, where two state bureau of investigation officers ask the killer for directions, not knowing that he’s the person behind the murders that they’ve been looking into, but the vibe is immaculate.

This sequence was my first encounter with the music of Townes van Zandt. Since then, I’ve listened to some of his other songs, but this is mostly the one I gravitate towards, and I occasionally find myself collecting and binge-listening to different versions of it. I love weird covers of songs, but some simply invite recreations of an original (or an “original” in the case of “Mad World”, originally by Tears for Fears, but the piano version by Gary Jules from Donnie Darko tends to be the one everyone references; it’s like that Baudrillardian bit about simulacra, where the original becomes lost – as is definitely the case with “instrumentals” of the song which are made only in reference to the Jules version. The best one, obviously, is by metalcore band Evergreen Terrace.) “Lungs” doesn’t really do this – there’s a gravity to the original, and even when other versions diverge – such as the cover from S.G. Goodman’s single or Boo Hewerdine’s more...darkwave?...attempt – hew pretty close in certain important ways.

The original is from Van Zandt’s self-titled 1969 album, and is the first track on the album’s second side. Mark Lager of Vinyl Writers characterize it in 2019 as “a bleak, stark and tough tale about the lives of miners.” This matches what William Ruhlman wrote about it for AllMusic in his review of the album, noting that “As usual, his closely observed lyrics touched on desperate themes, notably in t[h]e mining ballad ‘Lungs,’ but they were still highly poetic”.

Characterizing this as a song about mining makes a certain amount of sense. There is an invocation of suffocation and a mention of silver, Van Zandt is a finger-picker, it’s entirely conceivable that he might adopt the perspective of a Nevada silver miner and it would be entirely in keeping with his persona.

It also engages only with the outermost layer of the song – which is fitting for people who are reviewing the album instead of analyzing the song.

※

As per Wikipedia, Van Zandt was born in 1944, in Fort Worth. He died in 1997 in Smyrna, Tennessee at the age of 52. He was apparently a smart kid – his parents thought he’d be a lawyer or politician – but he was mostly interested in music. In 1962, he started attending the University of Colorado at Boulder, and by his second year, he was suffering from bouts of depression and his parents had become worried about his binge drinking.

The treatment used was insulin shock therapy. This was an early pharmaceutical intervention, where the patient was put into a coma for a time by spiking their insulin levels. Van Zandt’s treatment is described by Jim Manion, writing for Totally Adult magazine in 1998 as being the result of his “intelligence and ultra-sensitivity [getting] the best of him, leading to a mental breakdown, diagnosed as manic-depression with schizophrenic tendencies, the resulting hospitalization and insulin shock therapy wiping out much of his past. After this harrowing experience, with his deep wisdom still in him albeit in a rawer form, Townes hit the road in the early sixties with the vision of expressing his haunted and deep thoughts through words and music.” In a piece for Texas Monthly in 2006, Michael Hall wrote that

Townes met Fran, and the two started dating. Not all, however, was well: In the spring of his sophomore year, his parents, who were living in Houston, flew to Boulder to bring him home. ‘They thought he was binge drinking and suicidal,’ remembers Fran. Townes’s parents admitted him to the UT Medical Branch in Galveston for three months of insulin shock treatment. ‘It was a time when they used extreme measures for things like that,’ says Fran. ‘He seemed okay to me. He seemed like a normal college student.’

The subjective experience of going into an insulin coma involves breathing becoming difficult, and often – including in Van Zandt’s case – involves the loss of long-term memory.

So, with this in mind, consider that Van Zandt was placed into this treatment by his parents, and half a decade later released a song that begins with the line “Won’t you lend your lungs to me? Mine are collapsing.”

※

The word “I” appears only in the first and last verse of the song – the rest of the time it’s in second person. I read this, personally, not as the song of men working in a mine, but as the experience of a coma dream. The vignettes that Van Zandt places in the song dig through layers of meaning, parallel to the speaker of the song – speaking, I believe, largely to himself – sinks deeper and deeper in the fashion of a katabasis into a sort of imaginal soup of concepts, all of the boundaries in his mind fading away.

There are four verses. The first is the speaker reporting his experiences in the waking world but losing touch with “reality” as we experience it. He asks the listener for the use of a pair of lungs, as his own are collapsing. His body, the very material basis for his life, is no longer able to support him and he attempts to reach out for help.

Later on in that first verse, we find a very charged line “Stand among the ones who live in lonely indecision.” The ambiguity here is, I feel, key. Oftentimes, with ambiguity, the temptation is to try to collapse it, to make it read one way and not the other. The obvious route would be to claim that “the ones who live” are in lonely indecision: the people around him as he is put in treatment are lonely and indecisive, not having seen the trouble he was in before now, which leads to the extreme course of treatment that he’s undergoing. It’s also possible that the one instructed to “stand” – the listener – is doing so in lonely indecision. If we take this to be autobiographical, and I’d argue there are autobiographical elements here, then the speaker is describing, ultimately, being unable to advocate for himself: his parents believe this is necessary, but he does not – and he is unable to speak up, unable to prevent this thing that he feels is unnecessary.

Van Zandt did have what, at the time, was called Manic Depression with Schizophrenic characteristics. We would probably call it, today, Bipolar Disorder with psychotic characteristics, or potentially Schizoaffective disorder – I’m not attempting to diagnose him, I’m not qualified, and even if I were qualified, doing so without having met the guy would be unethical. However, I’m trying to interpret how he was labeled in terms that a modern reader might understand. He might have acknowledged that there was something about his experience of the world that didn’t line up with that of other people – which might make him feel isolated, and the extreme nature of the treatment might have brought him up short and left him in indecision.

The second verse is likewise ambiguous. I read the whole song as being about the experience of sliding into a coma during insulin shock therapy, but the opening lines “Fingers walk the darkness down, mind is on the midnight / gather up the gold you’ve found: you fool it’s only moonlight” makes it seem as if he is talking about the experience of playing his guitar – Van Zandt was a finger-picker, and it sounds to me as if playing music might have kept a metaphorical darkness at bay for a time. However, this dream proves to be untenable, the rewards as ethereal as moonlight, and the speaker opines that the listener “better leave that dream alone and try to find another.”

While good and evil are often portrayed as at odds with one another, there are moments in the Abrahamic tradition that show what can be seen as a certain degree of cooperation and complicity between the two — the Book of Job is an example of this.

The third verse is what really catches my attention, though. It opens with the lines “Salvation sat and crossed herself and called the Devil ‘partner’ / Wisdom burned upon the shelf. Who’ll kill the raging cancer?” a couplet that seems to contain within it a whole theory of suffering, and what I’m mostly fixating on in this close reading of the song: without the threat of damnation, salvation means nothing. Without suffering to act as stick, no amount of carrot will achieve the desired ends. As we focus on the petty dramas of our lives, real solutions to real problems are being ignored. Good and evil are entwined with one another because those categories are things found in human readings of situations.

The song then turns its attention to the natural world, describing a river that has been dammed – its mouth “sealed” and the water as having been “taken prisoner”. The juxtaposition with the more religious content of the first half of the verse is a bit confusing. For me, it brings to mind a kind of universal suffering, climbing from the natural world to the human world and emerging into the supernatural – especially as the final line describes a screaming rising to heaven and then being answered.

The fourth and final verse turns back to a Christian context, but does not do so in a way that forecloses what was discussed previously. While it mentions Jesus by name, and claims rather traditional things about him (that he is an “only son” and thought only of love), it laments a lack of connection between people – of suffering strangers who “dirty up the doorstep” that the speaker acknowledges they can’t really help, though they will claim that they tried.

※

The song is clearly about suffering – physical, mental, spiritual – but one might ask about the penultimate word of the title of this piece: what here, exactly, is “eerie”? I first conceived of this piece as an attempt to do a Fisherian, The Weird and the Eerie-type reading of a song. There does feel, to me, to be an eeriness to the music here, though I admit that might be influenced by the context I first encountered it in.

Let’s turn back to Fisher’s original text for a working definition:

The feeling of the eerie is very different from that of the weird. The simplest way to get to this difference is by thinking about the (highly metaphysically freighted) opposition — perhaps it is the most fundamental opposition of all — between presence and absence. As we have seen, the weird is constituted by a presence — the presence of that which does not belong. In some cases of the weird (those with which Lovecraft was obsessed) the weird is marked by an exorbitant presence, a teeming which exceeds our capacity to represent it. The eerie, by contrast, is constituted by a failure of absence or by a failure of presence. The sensation of the eerie occurs either when there is something present where there should be nothing, or is there is nothing present when there should be something (p. 61, underlining is italics original.)

In addition, the particular passage that made me wish to explore this song came from his examination of Stalker by Andrei Tarkovsky, which I watched with some of my students at the end of last semester. Fisher described the title character as “[h]umble in the face of the unknown, yet dedicated to exploring the outside, the stalker offers a kind of ethics of the eerie” (p. 117).

If there can be an ethics of the eerie, then could there not be other means of approaching the same topic – aesthetics of the eerie (granted, it is, itself, originally an aesthetic concept) centered on the juxtaposition of presence and absence, or hermeneutics of the eerie that attempts to interpret not what is absent in the lacunae of a text but the absence itself, or (as this piece itself suggests) a theodicy of the eerie?

I’ve known about Aaronson’s study for a long time, but I’ve not had a chance to really look deeply into the methodology and responses to it.

What we find in this song is absence. The speaker is absent from himself, as Van Zandt was absent during the insulin shock therapy. I am reminded of Bernard Aaronson’s hypnosis experiment, detailed in the chapter “Time, Time Stance, and Existence” in the book The Study of Time (a psychology book produced in West Germany in 1972 – given the state of social science from the time, I’m somewhat leery about it, but I’m not sure anything like the study has been done since. It is sadly not available in full.) In it, Aaronson and his colleagues used hypnosis to temporarily remove or expand perception of a “direction” of time from three subjects and had a fourth “control” subject immune to hypnosis (some people simply don’t fall into a trance it seems) who was intended to role-play what he thinks each state should look like, but who the hypnotists, themselves were not aware was immune. It is the presence of a control subject that gives me some grudging acceptance of the study, though I’m still a bit skeptical. Under the “no present” condition, two of the subjects became catatonic to one degree or another, and the third subject became deeply melancholy, though he admitted that “he had allowed his sense of the present to lessen rather than let it go, because of a presentiment that something very bad would happen if the present disappeared.”

This unstable data point, from Aaronson’s study, suggests to me that the subjective experience that Van Zandt is describing here could be thought of as a distortion of his subjective experience that involves the absence of the self from the self – the loss of the “present” function and the mind attempting to fill in the emptiness, to have something there.

One could see the first verse as the inspiration (ha) for this exercise, the imposition of the present emptiness on the speaker. There is a terror to it, and Van Zandt apparently once opined that this song should be “screamed, not sung”, though I can’t find an original to this statement, it was most likely in conversation. The subsequent verses move through folkloric, religious, and finally a kind of mystic consciousness which proves to be more stable. This is a textbook example of ekstasis as described by existentialist philosophers: standing outside of oneself, looking in.

So, what, here, deals explicitly with suffering and how is that eerie?

I take this song not to be a mining tune, but to be a story grounded in Van Zandt’s experience of Insulin Shock Therapy. To his perception, his parents – with whom it seemed he had a very good relationship previously – suddenly appeared and, in an act of loving kindness, spirited him away from his life, and then a doctor, a healer an authority dedicated to correcting harms, spirited him away from himself. It must have seemed like a great and terrible inversion of the order of the world.

This “form without content” issue echoes the idea of the doppelganger as a “familiar stranger” as articulated in Sigmund Freud’s The Uncanny. I can’t really shake the association, personally, though I’ve been marinating in doppelganger-fiction all year.

What we have here is the form of the world without its expected content. The apparent essence of things (of parents and doctors as a kind of benevolent authority) being removed and only the form of their power remaining. It is a kind of anomie, an absence-within-presence caused by the breakdown of the logic that guides how things should function.

The theory of suffering present here – as I read it, not necessarily as is present in the song qua the song – is that the forms and procedures that shape our world have an immense capacity to cause harm. Even the most beneficent of unequal relationships has potential for abuse, and we cannot fully correct that and have the relationship work: the surgeon has to have a knife, or else he isn’t a surgeon. There must be a capacity for harm or else there is no capacity to heal. The two are twinned.

So we are left with the situation where there’s always going to be the possibility for harm to occur, and that harm might occur not out of malice but out of misunderstanding. Importantly, understanding is not knowledge. If we approach things from a Christian framework, then we can understand Van Zandt as sneaking a sixth term into the problem: God may be all-good, may be all-knowing, may be all-powerful, may desire to end suffering, but does he understand suffering in the same terms as us?

Perhaps I should bring in Tom Waits’s maxim: “there ain’t no devil, there’s just god when he’s drunk.” That, of course, suggests a certain amount of malice arising from an external source, but from the point of view of a human being, it probably doesn’t really make all that much of a difference.

Of course, all of this hinges on taking things in theological terms – and I will admit to having a certain amount of sympathy for such things as thought experiments. I’ve spent a fair amount of time over the past five years or so thinking about such episodes from the faith of my childhood as the Binding of Isaac, and seeing it as in dialogue with the Euthyphro Dilemma, coming down rather firmly on the side of “what is good” being prior to and superior to “what is divinely commanded.”

So, in light of that it becomes more important to consider things from the immanent perspective, to think of things in terms of what it means with our feet down here in the mud. If we think of things in terms of the world being changeable – if the world is not simply an unmoving tableau – then there will be the possibility that some of those changes are painful. I’d argue that for any of it to matter, some of those changes must potentially be aimed at negative ends.

If the hand moves, if the pendulum swings, then change can happen — and in that case, suffering will no doubt come at some point. We have to work to make it worthwhile.

To turn it back to the song in a roundabout fashion, I think it’s far more important to “tell the world that we tried” than to think of there being an arc of history that bends towards justice. If we think of the world as inevitably getting better, then we ignore our duty to try to make it improve – but we also have to understand that, sometimes, the power to change things is the power to cause harm. As such, we need to bend not the arc of history but our backs to doing the hard work of doing good in a world that is neither inherently good or inherently bad.

Let us ignore salvation and the devil alike – to get caught up in that debate is to ignore that the two are often in cahoots – and instead let us take wisdom from its shelf and try.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Bluesky, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.