Edgar's Book Round-Up, May 2024

It has been an unbearably difficult time on several levels. Gaza still needs esims and an end to the genocide being carried out on it by the Israeli government using American weapons and money; on a more personal note, here is the gofundme for the family of a dear friend and Broken Hands collaborator who passed away recently and unexpectedly. That said, this past month was a very good one for books, overall. Links go to Bookshop, as per.

※

First up, we have Diavola by Jennifer Thorne, which I read in audiobook form — another recommendation from my favorite bookstagrammer and real-life friend. The novel follows Anna, a young woman roped into another of her family’s extravagant but utterly fraught vacations, this one in a relatively remote villa in Italy. Unsurprisingly, the villa is not as empty as one might hope, and soon, events escalate from unsettling to deadly. While this sounds like a conventional set-up — and it is — Anna is a charming protagonist and her family, a convincingly dysfunctional mess. Thorne also uses things that are just this side of plausible, like lost time, to great effect. I am not totally sold on some of the structural decisions Thorne makes in constructing the story — there’s a weird back-and-forth thing happening in the third quarter of the book, if I recall correctly, and it didn’t quite land for me — but overall, it was an enjoyably messy tale of hauntings of al kinds.

Such a great cover, too!

Next, in print, I finished Ferdia Lennon’s Glorious Exploits, which takes as inspiration a throwaway remark in Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War, and makes it into something fresh and strange. Lennon offers two Syrcusan losers in 410ish BCE, as they attempt to get the Athenian prisoners of war to put on a production of Medea. But Lennon isn’t really doing historical fiction — whatever is going on here is closer to the carefully selected anachronisms of The Once and Future King, or the comedic ones present to the costuming especially of Our Flag Means Death. To be clear, I mean this in a complementary sense, especially because Lennon never lets his comedy outweigh his tragedy, and the presence of the truly divine, moving, and terrifying present to both Euripides’ plays and the characters’ lives. Honestly, this one was kind of a keyboard smash of stuff I was going to like anyway, and I was not only not disappointed but, in fact, quite taken with Glorious Exploits, and if it sounds at all like something you might like, I would recommend it to you too.

I followed that with Lee Mandelo’s The Woods All Black, which I had greatly anticipated — all the more after reading Sarah Gailey’s delightful behind-the-book feature for it. It didn’t disappoint: the novella follows trans man Leslie Bruin, dispatched to a backwoods town in Kentucky by the Frontier Nursing Service. But a fiendishly close-knit religious community and something lurking in the woods around the town mean that Leslie is in for more than he bargained for, and it will take everything he has to get himself out — let alone the troubled tomboy at the center of the burgeoning violence wracking Spar Creek. Readers may recall that I’ve very much enjoyed Mandelo’s other works, and this one was no exception. Mandelo is a master of atmosphere that still doesn’t drown the plot, and I ate it all up in an afternoon. Both this and the previously mentioned book came to me via the good offices of my public library, which often has print books long before I could make my way through the Libby holds queue, which seems worth mentioning.

I think this the paperback cover, and I like it substantially better than the hardback.

Next up, in audiobook form, we have Rin Chupeco’s Silver Under Nightfall. I’ve discussed their works previously, and overall enjoyed them; while I can’t say I liked this one as much as, for example, The Never-Tilting World, it was nonetheless enjoyable. The plot follows a young nobleman, disgraced by accident of birth, as he transcends his troubled past as a vampire hunter to befriend — and befriend, if you take my meaning — two vampires on the side of rapprochement. As always, Chupeco builds a rich setting and their characters sparkle (but not like that other vampire series), and once the plot kicks in, it’s really grabbed me. To Chupeco’s credit, they also were able to capture both the raw coolness and the blatant silliness of anime-style weaponry, which is definitely tough to do, especially with something like a knife-chain. It just took a little longer than I’d have liked to get to the meat of the story, and also I had the distinct impression that I didn’t like Castlevania enough for it to really land for me. Still, though, I’ll be reading the sequel when I get the opportunity.

Next up, another audiobook, this one recommended to me by a friend: Islands of Abandonment: Life in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn. In a vein that reminded me oddly of Annalee Newitz’s Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age (reviewed here), Flyn explores landscapes that have been, for one reason or another, abandoned. Ranging from Chernobyl’s famed exclusion zone to the Bikini Atoll to a tiny island off of Scotland, where dwell only feral cows, Flyn draws out the similarities between these places reclaimed by nature, often from the worst excesses of human violence, to begin to draw a path forward from the environmental devastation we see around us. And while Flyn shows the beauty of these places — often less abandoned than they are reputed to be — she is nonetheless quite clear on the urgency of working against that devastation. It’s an incredibly moving book (I am, in fact, a little choked up thinking back on it), and a valuable one. Possibly especially, this strikes me as crucial for people interested in speculating about the future and how it will look and how it will vary from the world we now live in, but that may only be because I am such a person.

I followed it with another audiobook — there’s a lot of those on here, mostly because of the remaining print book — Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield. Released to some acclaim (this Autostraddle review captures the tone pretty well) two years ago, it follows Miri, a civil servant working from home as she attempts to care for her wife, Leah, who returned from a mysterious deep-sea dive utterly changed. Armfield’s portrait of a relationship in crisis is gently devastating: in the inexplicable symptoms Leah experiences and the strain they place on the already-strained Miri, Armfield delves into the grief of watching someone die by inches, probing at what love means and how loss works on it, and vice versa. Yet that love is never really in doubt, which is Armfield’s real triumph here — when the story is painful, it’s because Miri and Leah’s relationship feels real and meaningful. It’s not a long book, but it is a highly effective one, and I hope to read more of Armfield’s work.

Thanks, KU Libraries!

The last print book in this round-up is Craig A. Williams’ seminal Roman Homosexuality. As many others have noted, the title is a little bit misleading: what Williams’ achieves is a careful dissection of Roman masculinities, and how they functioned in relation to class and propriety (there is very little discussion of same-sex relations between women, but Williams is pretty up-front about that). As he notes early and often, to characterize same-sex relations between men in Rome as “homosexual” doesn’t have much to do with the ways Romans themselves characterized them, which had much more to do with the relative social classes and who was penetrating and who was receiving. Williams assembles and analyzes a terrific amount of primary source material, ranging from Plautus’ comedies to writings well into the Common Era, to prove his point: if you were a Roman man, one of the toga-wearing class, your masculinity was unquestionable so long as you were the penetrating party and coupled only with boys, your wife, your own slaves, or sex workers. Williams spends a great deal of time working through what he terms the “prime directive” of Roman masculinity, devoting a chapter to each of the points he raises in the beginning of the book to this effect, as well as a fascinating exploration of what, precisely, cinaedus means. It’s truly phenomenal academic writing, and I have no doubt that, as I continue my classical studies, I will return to it again.

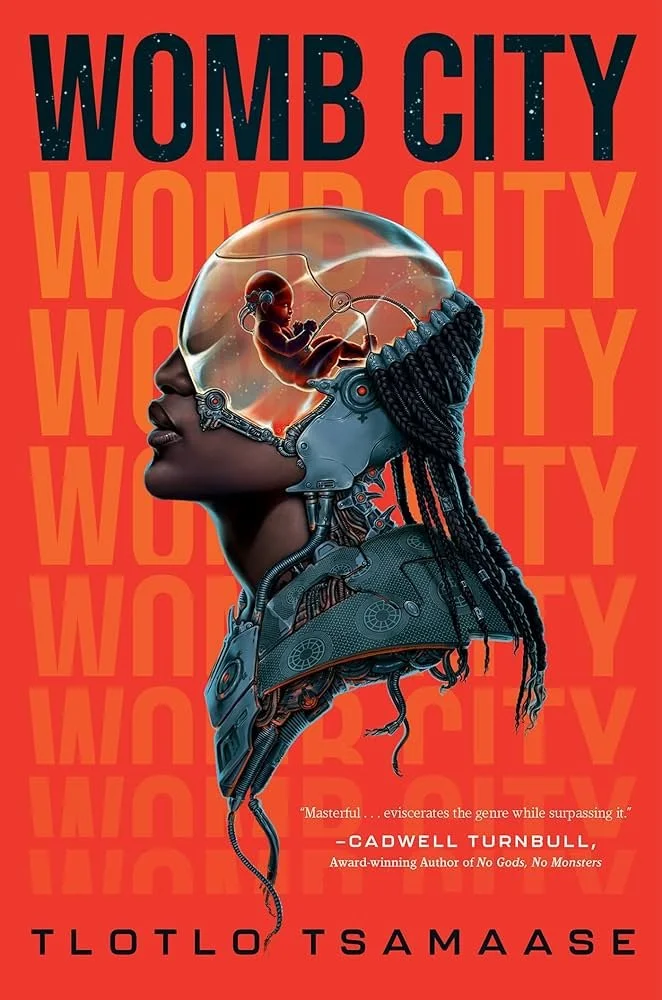

As I continued working through that, I also absolutely devoured Womb City by Tlotlo Tsamaase in audiobook form. The novel is set in a future Botswana where body-hopping is common, and so is overwhelming surveillance for some, overweening corruption for others. Nelah’s consciousness was placed in a body that is missing an arm and is microchipped because of a past crime; she wants to have a child, but cannot, and her husband is privy to her every experience as a high-ranking member of the police. Her life hangs constantly in the balance — and that’s before a night of indiscretion ends in a murder, thrusting her into the special hell of the Murder Trials. I picked this one up because it was available immediately and looked really, really cool, which it absolutely was; it also avoided the kind of transphobia I feared it might lead to, given the blurb. Instead, Tsamaase, who uses she/her and xe/xem pronouns, offers a relatively nuanced approach to gender and misogyny through the lens of a character — a consciousness — who remarks that, in an ideal world, she would have access to three bodies, one female, one male, and one androgynous. But the prevailing culture of misogyny and global racism circumscribe any dream she might entertain about transcending societal demands (up to a point). Tsamaase also makes rich use of Botswanan myth, skillfully blending the fantastical with the science fictional to draw the novel to an immensely satisfying conclusion. This is Tsamaase’s first novel (which is treated in LARB at greater length, for the curious) and I cannot wait to see what xe does next.

We close this roundup with the audiobook version of a pulp classic: Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest. One of a few novels Hammett wrote about the Continental Op, and a fix-up of the short story “Nightmare Town,” the novel follows the Op as he is summoned to Personville by a man who never appears alive on the page, and rapidly finds himself embroiled in the politico-social rot of a place even the locals call “Poisonville.” It’s a fuckin’ bop, quite frankly. That the Op is no more immune to the corruption at the heart of Personville makes the novel especially delicious; it’s been argued that the novel is a Marxist indictment of then-contemporary society, and I can definitely buy that reading (though here’s a cool article I found about Hammett’s politics that gets into greater detail). Personally, I really enjoyed being reminded that part of the charm of this era of noir fiction is how bad the cops all suck. It’s great, and served to remind me of how much I enjoy Dashiell Hammett’s writing.

※

That’s all I’ve got for now. Follow me and Cameron on Bluesky, or Broken Hands Media on Facebook and Tumblr.