Nobody's Smart: Intelligence Doesn't Actually Exist

I was fascinated by Einstein when I was younger, but you would not believe all of the inspirational pablum attributed to him over the years. It’s almost impossible to find out anything real about the man beneath all the mythos.

The semester’s getting off to a slow start. The two schools are staggered in the dates they begin, so it’s been a little bit rocky, but more in coordinating, rather than in getting the actual work done. As it does, I think about the business of teaching, and about what worked for me in the past.

One of the biggest changes in my mindset over the past eight years – the course of what I might call my “teaching career,” which I’ve discussed from different angles on this blog – is that I no longer believe in intelligence as an inherent quality. There’s a lot of talk about this in the broader culture: one famous quote goes along the lines of “everyone’s a genius, but if you judge a fish by it’s ability to climb, then it will go through its whole life thinking it’s a failure.” That’s often attributed to Albert Einstein, but there’s no evidence he ever said it: Einstein’s name is often just added to such things to give them a patina of intelligence (undermining the point of the quote in the process, I’d argue.)

It’s easy enough to get to here: no serious person thinks that an IQ test reveals anything important about the person taking it. Famously, these tests are more an assessment of cultural competency, and serve as a backwards justification for the way that things commonly work in the society where they’re being administered.

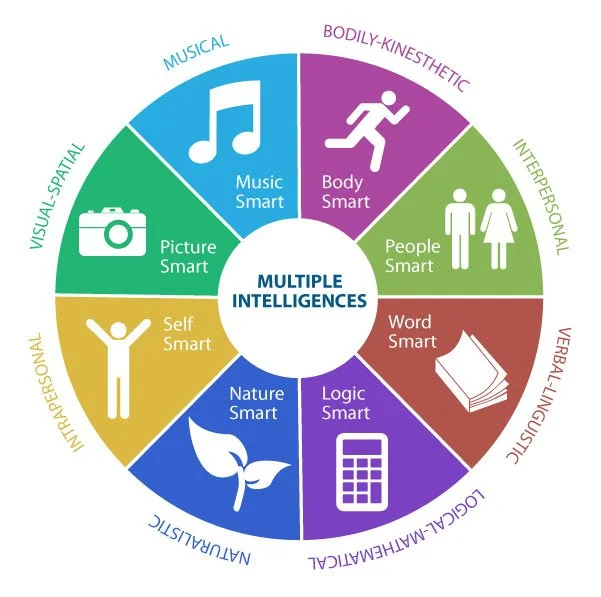

I’m sure we’ve all heard this theory, but here’s a handy diagram — By Sajaganesandip, used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license — that explains it.

The first step after this is Howard Gardener’s idea of Multiple Intelligences. This is where discourses about Linguistic Intelligence and Musical Intelligence and Kinesthetic Intelligence come from – there are different ways that someone can be intelligent. And so we have gone from a count of one to a count of many. All you need to do to be intelligent is to find out what kind of intelligence you have and lean into that strength.

I have both a philosophical and a practical issues with this.

The philosophical issue is that this still leads to meritocracy, which I don’t trust. It creates a judgment based on a kind of meta-intelligence: you have to figure out what your kind of intelligence is and figure out how to apply that. However, all of this leads to an issue where there are going to be some people who are losers and we’re just supposed to be okay with that. It’s impossible for everyone to be a winner, so we have to accept that some people are just going to suck at most things they try.

Don’t worry about how this always lines up with the distribution of resources that existed status quo ante.

The practical issue is also an emotional one: I don’t like to fail students, but I also don’t like to make things easier than they have to be. So I have to find ways to push student achievement higher. This, I feel, is a fairly common stance for teachers to take, but there are only so many ways you can encourage students to change their approach.

So what if we move things in the opposite direction we’re inclined to. What if we move from one to zero instead of from one to many? What does it mean to bracket off and suspend the category of “intelligence”?

We also have to bracket off those other categories that fall under it – we’re taking spatial and kinesthetic and linguistic and logico-mathematical intelligence and we’re putting them on a high shelf and seeing what’s left behind.

I’m reminded of a friend of mine from high school. He was a frustratingly talented person to sit next to in class: not only was he an accomplished actor and vocalist, he sat behind me in a few of the advanced English classes I took and spent all of his spare time drawing. This young man could sketch, comfortably, in pen, and have the outcome look good. This was achieved because he had practiced endlessly.

She's still at it as part of the band Tombseeker.

Another high school friend of mine has become an accomplished musician because she couldn’t hold a guitar or bass without noodling through a complex set of riffs. Our circle of friends created an eponymous verb for it, applying her last name to the act of playing continuously at a low volume. I think it was, at least partly, a way of managing anxiety, of burning off excess energy, but our friends still discuss her musical skill with a note of awe and respect.

This, I think, is what we call “talent” really is: if you are enthusiastic enough about something that practicing it becomes as regular as a heartbeat, then “practice” becomes invisible. When you do something to the degree that it becomes synonymous with who you are, we can say that you have a kind of genius with regard to it. Now, we want to think about people as “being” geniuses, but I think talking about it as a thing you have is a much more accurate way of discussing it: If it’s something that you are then it becomes about merit again. It becomes about you being somehow special. No one I have met who has a genius behaves like this: it seems, either to them, to the observers, or to both as if something is riding them. The genius isn’t necessarily something separate, but it feels as if it has a kind of autonomy.

This, I think, is connected to the quality we often label “intelligence”, which is really a factor of enthusiasm. In the domain of these intellectual skills, are you interested enough to keep doing something if you’re bad at it the first few times? Are you invested enough to try to improve?

In turn, this makes teaching a very different proposition. The job isn’t about finding and nurturing those students who are intelligent, it’s about persuading people to engage with the material and to have enough grit to keep going when they aren’t perfect the first time, and the deeper understanding of self and subject matter that work engenders.

Because, frankly, I think it’s kind of bad in the long term if a student is perfect the first time. I’m not going to put my thumb on the scale to ensure that they’re not, but it strikes me as leading to some very shallow roots that can quickly lead to discouragement. They’ll be convinced that they have this “skill” that sits in their back pocket and they’ll never ever get rusty at it, and as soon as it fails them, they’ll decide that they were simply wrong and they’re no good at it.

On the other hand, the student persuaded to work at it will value the skill they’ve gained, and will eventually master it.

Johann Wilhelm Schütze's Bacchus with Leopard. "Enthusiasm" in Greek commonly refers to the spirit of the God -- usually Dionysus or Apollo -- taking over the devote. This....isn't quite what I'm going for, but it allowed me to use a somewhat overwrought painting as an image.

I only occasionally had to try in school up until I got to graduate school. This, generally speaking, is how one gets graduate school burnout: you coast through and think you’re the best, then you hit a slight incline, a bit of difficulty, and you’ve never had to study, you’ve never had to work and you don’t have the grounding for it. I hadn’t developed the skills to drill down and really get everything done – I was just good enough at it beforehand, and my own enthusiasm for the subject I was studying carried me through.

I view this as also part of my job: I need to persuade them to try, even if they aren’t inclined; I need to provide friction so that they get in the habit of working.

That, then, might be the best thing to focus on instead of “intelligence” – the question isn’t “are you smart”, but “do you have the right habits to carry you through”?

Of course, what one might be asking, after having read all of this, is “that’s all fine and good for you as a teacher, but how could I possibly use this in my life?” The answer is fairly simple from where I’m standing: if you want to get good at something, even something very basic, you have to do it a great deal. This means that you need to clear time and make yourself do it, and all of that is easier if you have enthusiasm for it.

If you want to have a green thumb, for example, you have to be enthusiastic about plants: you have to make time to tend to them, you have to put together information related to them, you have to think about them when you’re doing the so-called mindless tasks of being alive – sweeping, cleaning, folding laundry – and all of this is much easier if you actually enjoy doing it.

This is where the difference between liking something and liking the idea of something comes in. To take the green thumb example from the prior paragraph, you have to actually like doing things with plants. You’re not going to get very far if you don’t want to get your hands dirty.

Of course, this aside about such things as growing plants might seem like a bit of a digression in a piece on intelligence. The same thing is true for those talents we often conflate with one another and label as “intelligence” – largely reading, writing, figuring, and critical thinking. Most of the rest of it is simply recalling facts, and that’s mostly just window dressing because (I’ll be honest with you) the recollection of names, dates, and trivia is a fairly low-level skill. I know this because I’m fairly good at it.

But the point of all of this – education, pieces of writing like this – is that these are things you can practice, things you can get better at, and – unfortunately – things that you can lose if you don’t use them often enough.

I think there's probably a reason that the Greeks personified the Arts in the way that they did -- I have no bona fides to support this assertion, but the relationship between the artist and the art could be thought of as something like the relationship between two people (Image is Hesiod and the Muse by Gustave Moreau, from the collection of France's Musée d'Orsay.)

The whole thing gets much easier, in my opinion, if you like it. I would also argue that, should you be struggling to learn a skill, the first thing you should do is find something in it that can fascinate you and draw your attention to it. You need to romanticize it to a certain degree.

If you wish to learn a language, find a television show or book in that language that interests you. If you want to get a green thumb, discover a plant you want to grow in your house. If you want to write, find a story idea that you cannot live without putting into the world.

You have to love it enough to do it badly, and then do it again a bit less badly. You have to become a bit of a sicko and pervert about the skill, and you have to do it all over and over.

There may be limits to what you can do – I’m just shy of 38, out of shape, and I’ve got bad knees, I’ll probably never dunk a basketball – but if you can learn a skill, then loving it is the easiest way to develop it.

You also need to recognize that the things we call “intelligence” are just a cluster of skills. If you can pluck them apart and recognize them as things that stand on their own, then you can practice them. You just have to figure out how to practice them.

※

That’s all for now. You can follow Edgar and Cameron on Bluesky, or Broken Hands on Facebook and Tumblr. If you’re interested in picking up the books we review, we recommend doing so through bookshop.org, as it supports small bookshops throughout the US.