Screw the Line, Save the People (Odd Columns #7)

The Great Recession ended, supposedly, sometime in the Summer of 2009. You wouldn’t know that if you talked to anyone actually working a real job. You would think that it had never ended, because for many of us it never did.

For the first few years of this period – now in its thirteenth calendar year – I was doing fine, financially, because I was in graduate school and I was getting paid for it. I went to a safe school that offered me a good deal, though, instead of one of the more prestigious schools that I was accepted in to, but which didn’t give me the support necessary to pay for everything. Sometimes I’m haunted by the thought of what my life might have been like if I had made different decisions, but the past is like concrete. It’s set.

Since getting out of graduate school, I’ve worked a variety of shit jobs of one form or another, and I actually really like teaching, but my heart sank when the lock down started – not simply because online teaching is strange and unfamiliar (and ending far too early.) My heart sank because my students were going into debt to attend school online, and many students going to university online were paying full price for something that didn’t cost all that much to put together (I know — I’ve seen my pay stubs.)

This meme is compulsory for this discussion. I used it’s opposite for the cover image as an eyecatch.

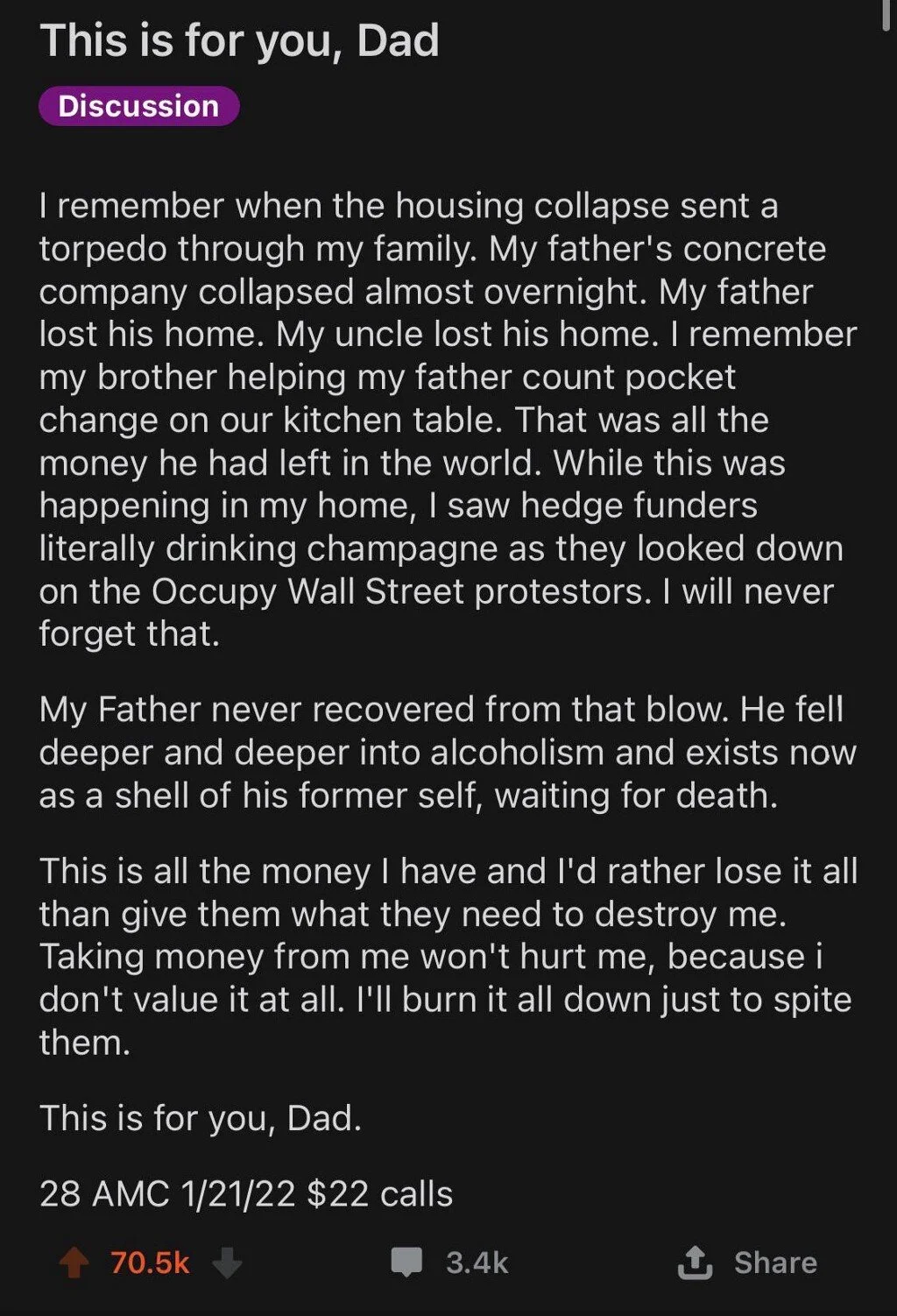

These thoughts were still lingering when the “Gamestonks” Fiasco began to emerge into the popular consciousness (as of yesterday, word has spread that this is making it to congress – remember, folks, they’re doing quite a lot of immaterial things for a bunch of people that owe you $2,000.)

It’s essentially a less-visceral form of Haruspicy.

I bring up all of this as support for something that I’m sure we all know and feel: the stock market isn’t real. It is, fundamentally, a theological fiction. I say “theological” for two reasons – first, the functions of the stock market are treated as a kind of augury, and second, finance grows out of political economy, which grows out of moral philosophy, which grows out of theology. It cloaks itself in obscurantism and technical terminology, masquerading as both profound mystery and settled science at the same time.

If the last year has taught you nothing, it has most likely taught you that the people in charge of our society are willing to sacrifice hundreds of thousands of people to make a line go up – and they’re not particularly good at making it do that. This eventually led to a bunch of redditors to play a massive and costly practical joke on a bunch of hedge funds short-selling the stock of a video game retailer that many of them were nostalgic for.

There’s more to the whole affair, but I’ll be honest: it’s not really that important for this particular discussion.

I’ve yet to finish it, but at a few different points, I’ve attempted to read The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein (I need to go back to it, honestly.) This book described, exactly, the playbook for the implementation of contemporary Capitalism in the “southern cone” of South America (Pinochet’s massive deregulatory push being the thin end of the wedge on that one. As I noted previously, Fascist regimes, far from being examples of a centralized economy are actually massive engines of deregulation) and it also fit with the narrative of the economy of the Global North following 2008.

After 2008, home ownership dropped, wages stayed flat, rents went up. I know very few people that had the privilege of working only one job at a time over the past decade. I, myself, was at various times working either two or three jobs. Now that I’m largely working only one, I feel like a loafer (and still can’t make ends meet reliably. I’m going to have to go back to the grind soon enough.) In the post-2008 regime, low interest rates meant that finance was relatively easy for certain sectors of the economy to secure – leading to the bizarre phenomenon of the command-based market actor: Netflix, Amazon, and other large actors are essentially miniature command economies embedded in the larger market.

This also means that, to a large extent, they are unmoored from the demands of the market. It’s essentially the soviet system, but somehow less satisfying or efficient.

My fear is that the economic legacy of 2020 is, essentially, “2008, but more.” Consider restaurants: chain restaurants are managing to survive by shifting their focus to places that have less stringent lockdowns. Given the way the virus travels and the way that people respond, every regional market will have a crunch, and every regional market will have a period of stability. The larger business can survive by feeding its starved limbs off of the ones that are still able to function. Local restaurants don’t have this luxury: they are moored to a particular location, and survive or fail by this location.

Both are extractive businesses, but I’ll admit an affection for the local restaurant. It makes me feel a greater sense of community, and there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism, anyway.

I worry that, post-Pandemic, the best we might hope for is that some chains operate under the same model as funeral homes: wearing the veneer of the local, single-proprietor business, while actually a sock puppet of a larger entity. Chances are that your local Mexican restaurant will be a Chipotle or a Taco John’s, your local bar and grill will become an Applebee’s, and all local character will evaporate.

I bring this up not simply to give a dire warning about how it will feel to live in an American city in five years or so, but to make the prediction and then explain that there’s no reason for this to happen.

Look: all of this is predicated on the stock market, and the Gamestonks Fiasco is showing just how much bullshit it all is. The stock markets are not something real: they are an image, a representation of the actual market that exists out in the world. People make decisions based on it, but the vast majority of the people doing this are making decisions not to influence the reality but the image of the reality.

Look: you can’t change the path of the storm by drawing on a map. We had a big laugh about that a while ago.

The map doesn’t change where value is. Value is not created or lost by the stock market, because it’s simply a representation. Thinking that altering the reality by manipulating the representation is magical thinking, which is fundamentally what finance is: magical thinking dressed up in a genteel suit and tie.

That’s also what the Gamestonks Fiasoco is about, whether the participants are fully aware of it or not: it’s a concerted attack on the holy image, showing how it has become unmoored from the actual reality it was originally meant to represent.

I tried to find an image of Joseph E. Stiglitz in the style of the introduction of Hugo Stiglitz from Inglorious Basterds, but no one else has made it, and I lack the photoshop skills.

I’m not the biggest fan of John Maynard Keynes, but I must admit that some of his thoughts appear attractive from my position, deep in the gullet of a nonfunctional neoliberal failed state. One of his predictions was the “euthanasia of the rentier.” His prediction was that stocks, bonds, patents, rental properties, and the like would eventually wither away as parts of the economy. This obviously didn’t happen, and in the hands of Neo-Keynesian economists like Joseph E. Stiglitz, it became not a prediction but a prescription: not “this will happen” but “this should happen.”

What happened instead was, of course, the exact opposite: the rentiers conquered the world and are now charging the rest of us a monthly fee to continue to live in it. Of course, the solution is to become a rentier. You, too, can live off of “passive income”, unlike those greedy parasites that expect everything to just be handed to them. Now, if you don’t join this class of people, you’re doomed to work until the day you die (remember, retirement funds aren’t bank accounts: they’re collections of stocks, bonds, and the like that are traded and produce value for the person they’re attached to.)

All of this is very, very stupid.

Even if we accept that the market is good and stocks should be traded and the like, everything involved is just so profoundly stupid, because it’s been clear since the beginning that there is a surefire winning strategy: just by index funds. All stocks are bets, index funds are just the bet that “yeah, there’s totally going to be a market in the future.”

The problem is that we’re just addicted to the idea of getting a perfect, gigantic result from such things, and the return on an index fund is always going to be low, because it’s a safe bet.

I can’t help but feel like there has to be a better way to distribute prosperity than bullshit numbers magic – which I stress to you, is exactly what the stock market is – and the whole fiasco in question is this fact writ large. Of course, there’s no political will to make this shift happen because we’ve largely surrendered our political apparatuses to the very people who benefit from the system being as it is: of did we forget the cadre of congresspeople who dumped stock as soon as they heard that the pandemic was happening?

This apparatus doesn’t work, and only concerted effort from low-level actors will fix it.

I predict that, without consistent pressure, the only thing that will come of this is additional constraints on retail investing. If the market must exist, then the “bullshit numbers magic” of such instruments as short-selling or subprime lending must be abolished. This is not the preferred solution, though.

We need to recall that the stock market that so many people’s fortunes live and die by is simply a representation. The Line is not real. The Line only has as much meaning as we give it. For far too long we have been willing to sacrifice people so that the line goes up.

This is exactly backwards. Here’s the platform, six easy words to remember:

Fuck the line. Save the people.