W(h)ither Cyberpunk?: A Review, an Experiment, an anti-Manifesto

(Note: the title of this piece is very similar to one used by a fantastic episode of Wyrd_Signal, which featured Dr. Elizabeth Sandifer, the writer of perennial favorite Neoreaction a Basilisk, who recently put together a materially interesting blog post on the subject of cyberpunk. I’m linking so people might check all of this one out, too.)

The boldest aesthetic choice here is the use of yellow as a dominant background color.

As I write this, I’ve sunk about fifty hours into Cyberpunk 2077, and I can’t rightly say whether I’ve enjoyed it. The game is certainly compelling, but I’m not sure whether I think it’s any good, really. There are a number of major issues with it that both include and are completely separate from the much-reported technical issues.

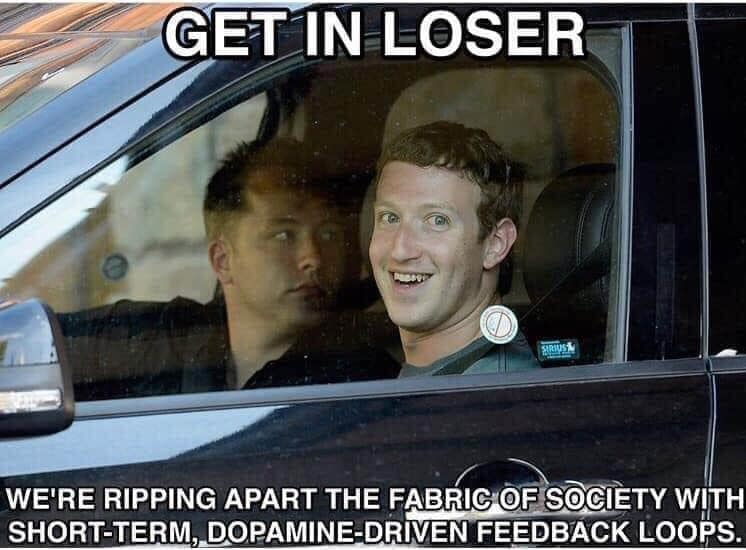

The mechanisms for this are very clear to me: there are a lot of small tasks involved in the game that take about 15 minutes or so to complete, and each one is about 75% satisfying. So you complete one, it gives you a hit of dopamine about three-quarters the size of what you were looking for, and then it begins to recede. By the time it’s gone back to the baseline, you’re already starting the next task. It’s a masterful example of the same short-term dopamine loops that drive constant engagement with social media: you get a hit, but you’re not satisfied, and you go back for more. By the time you get another one, the first one has worn off.

What makes the video game Cyberpunk notable is that it manages to do this with narrative. What makes social media notable is that it manages to do this with social engineering. Cyberpunk is possibly more honest because it charges you once, up-front for the experience, while social media is milking you for salable data even when you’re not touching it.

Using this meme is going to tank the facebook reach of this page. I know it, and I’m going to keep using it.

I find the whole business very frustrating, though, because as I noted, cyberpunk is the genre that most accurately reflects the modern day. An open-world cyberpunk game is the sort of game most similar to a hypothetical open-world modern day RPG (my love for the Persona series, a spin-off of Shin Megami Tensei is derived from the same source, and arguably gets closer), which is something that I think would be very interesting. Of course, you’d be looking at the whole thing from behind a gun, because the shooter is the genre of game that never seems to quit.

It’s whatever.

Image supposedly of 1980s Akasaka, in Tokyo. The origin is apparently impossible for google to find.

Of course, the story around its production – with constant broken promises and exploitation by the studio, the watering-down of the anti-capitalist content with neoliberal orthodoxy (one of the main type of side-quests is one where you’re hired by the police to deal with petty crime) – is pure, uncut cyberpunk. Complete with “high tech low lifes” pirating the game, some of them send money to the original creator – Mike Pondsmith – directly through back channels.

The State of Cyberpunk

I’ve written about Cyberpunk a number of times, both as a titular feature and as a major adjunct to another point. I’ve argued that it near-perfectly encapsulates our present moment, and that it should be killed off as a genre. I don’t see any contradiction in these points.

Part of the problem with Cyberpunk 2077 (aside from the fact that it’s trying to be a synechdoche for the whole genre, as per the name), is that it’s just so damned nostalgic for a future that would be cool but wouldn’t be that fun to be in. The future painted by the game is already a retrofuture, and it goes to great pains to explain how we get to someplace like there from someplace like here, destroying the internet and invoking the names of corporations that don’t exist, positing wars that are fundamentally different from the ones that we fought and ignoring the forever wars that are unfolding.

The Stars My Destination (1956) by Alfred Bester is one of the more interesting speculative fiction novels of the 1950s — I put it above anything by Asimov and Heinlein, honestly.

I turn, as I often do when discussing the genre, to Neuromancer, its archetypal text: the first cyberpunk consciously written as something like cyberpunk (some people might name Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Dick, or The Stars My Destination by Bester, or invoke other writers, but Neuromancer is the first cyberpunk novel written in a world where the term existed). A lot of people misunderstand Neuromancer as a vision of the future, but it’s an unheimlich intensification of its present moment – a trick that Gibson did more explicitly when he wrote the Bigend trilogy, starting with Pattern Recognition in 2002. His goal wasn’t to write two-thousand-whenever, his goal was to heighten, to accelerate, all of the forces that he was conscious of in his present day. It was the early Eighties with the knob turned all the way up and broken off. The shameful thing is that this almost perfectly described the 1990s – hell, it almost perfectly describes today. People simply don’t realize it because of the lack of cybernetic limbs and brainjacks.

The real world didn’t copy cyberpunk, but it rhymed it, and then one-upped it. A novel set in the real 2021, that accurately reflects it, sent back to Gibson or one of his contemporaries, would be an incomprehensible trip: a hit of uncut psychedelia that would be both banal and mind-shattering (equal parts Dick and Ballard, shot as a documentary).

They would shrink away from it. They would put the knowledge of the future in a place they could never reach and would brick it off. They would turn to more comforting dystopias, and produce something more like Cyberpunk 2077, ignoring that the story of its production more accurately reflects the horrors that they’re predicting.

I don’t want to talk solely about the past.

I want to imagine: how do you excise the “retro” from this retrofuture? How do you make it an anterofuture? Or, better yet, a progfuture?

What happens when you take 2021, and then turn the dial up and break it off?

That’s what I want to see cyberpunk attempt. The question remains, though: would the end-result be recognizable as cyberpunk? Or would it – by definition – be a completely new kind of monster?

Retrofuture and Progfuture

Just to define terms, I’m using “progfuture” here to mean, specifically, the act not of predicting a future, but accelerating the present, taking everything that’s happening in the world right now and pushing it up to the maximum tolerance. This doesn’t mean that what I’m writing about is meant to be, specifically, a prediction. However, just as the Cyberpunk authors of the 1980s predicted much of what happened in the last thirty years (missing Jobsian Minimalism and the Twee turn, but pretty accurate otherwise), this might yield an accurate prediction.

If it does that, though, I stress that it’s accidental.

Evoking the Monster

Published in 2015 by Alfred A Knopf. Reviewed in my first-ever book round up.

The first and most notable thing is the climate. Some creators of cyberpunk and associated genres are bringing in elements of this, creating the hybrid genre “cli-fi.” Fraser Simons’s tabletop game Hack the Planet, and author Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife come to mind here, as does the latter’s earlier book The Wind-Up Girl.

Any vision of the future that doesn’t at least address the climate is a de facto retrofuture, in my opinion. It’s an unavoidable fact of our lives now; it will be an even more unavoidable fact in the future. The ubiquitous leather of cyberpunk is a relic of this, as are its brutalist mega-buildings, which would require huge banks of air conditioners for the upper levels to be even livable. Designers need to look to the tropical cultures for inspiration, deriving at least general principles from them: the future looks more like Thailand, Nigeria, and India than like Great Britain.

This will also most likely play into another major issue: violence. Cyberpunk is a violent genre; it reflects the 1980s concern with spiking levels of crime and social dissolution. Despite these fears – and they live on in those of your parents and grandparents – violent crime has largely tapered off. What we have, instead, is an escalation of home-grown radicalism, white-collar crime, and police violence. You’re much less likely to die because of a mugging today, or a botched home invasion, than you were back then. You’re much more likely to be the victim of vehicular homicide done by a religious extremist, neofascist, or an incel, or have your life savings stolen by some greasy dude in a suit, or get killed by the police, than you were back then.

A progfuture of the 2020s would not feature an overwhelming presence of street gangs or organized crime contract killers: it would feature conspiracy theorists promulgating their theories, it would feature cartels of white collar criminals, it would feature the police as an occupying force in the cities where they still operate, and it would feature paramilitary militias.

Now where have we seen environmental devastation and radicalization treated together before? Oh. Right.

Taking these two tendencies together, the future I’m describing might seem more post-apocalyptic than cyberpunk. But that’s a reflection of the world we live in.

Likewise, let’s consider the tendency of Orientalism in cyberpunk: according to Neuromancer and its imitators (including Cyberpunk 2077), the future is Japanese. However, Japan just slipped behind China as the world’s second-largest economy (and isn’t even the third-largest, if the EU is counted as a bloc), and is facing a demographic crash. This doesn’t mean that Japan isn’t culturally relevant, but simply that saying that the idea that the future is Japanese is a misstep.

Admittedly, some older cyberpunk acknowledges this – Snow Crash and The Diamond Age, both by Neal Stephenson, come to mind. However, Stephenson’s vision didn’t lodge in the popular consciousness to the same degree as Gibson’s did.

Another thing that largely seems inconvenient to many cyberpunk stories is the omnipresence of the internet. There is a physicality to the technology portrayed that seems utterly at odds with the direction that our material culture is going: the technology depicted in these stories is not descended from the Jobsian minimalism that we often see in the contemporary age; it’s descended from the DJ rigs of the nineties and the aughts – snaking cables, jacks of all varieties, ports placed on everything.

Zelazny is mostly remembered for the — admittedly excellent — Amber novels, but his science fiction will always have a place in my heart.

Cyberpunk that intensifies the 2020s would embrace the ubiquity of wireless connections, because how often are you truly without connectivity? Nothing is wired to anything else, but everything exists on two overlapping planes: the world of humanized matter and the datafied-world of inhuman semiosis. The connection is always-already made, the feat is making it work for you, or disconnecting from it entirely. (In this way, the proto-cyberpunk short stories in the My Name is Legion cycle by Roger Zelazny might be more prescient: the lead character in these stories is a man who has a backdoor into a database that contains information about every living person in the world, and uses it to create perfect aliases for his work as an investigator and saboteur, a concept that could easily be revived in our age of social media.)

Of course, as I noted previously, the main difference between the world-beyond-your-window and the world on the page of a cyberpunk story is the absence of prosthetic and implanted technology, to the point that Elon Musk, every dumb person’s idea of a smart person, the megachurch pastor for atheists, is actively trying to create it. (I, of course, stand by my rule of having nothing implanted into my body that was paid for by someone who owns a sapphire mine. It’s a narrow rule, but it’s a rule nonetheless.) Of course, as we can see with the current paranoia over the introduction of microchips into the bloodstream through the vaccine and the terrible opsec shown by boomer insurrectionists, you don’t need to implant something to have the same basic effect. All of the Parler data was scraped with an iPad, your ISP logs everything you look at, and your phone tracks everywhere you go and could easily eavesdrop on everything you say. It leads to a paranoiac state. Asking why it is not literally embedded in your flesh ignores the fact that it doesn’t need to be.

I honestly don’t think that we’re going to see that many more implanted devices, much less purely elective ones. Instead, I think we should look to biohackers for inspiration – though, honestly, most of what they do isn’t that good an idea. Still, there are stories about biohackers doing things like curing their own lactose intolerance. It’s only a matter of time before someone does legitimately hurt themselves with it, but there’s narrative potential there.

Of course, there isn’t necessarily reason to believe that purely elective modification won’t happen – technically, that’s what gender confirmation surgery is, and people who undergo that procedure have modified their bodies to function more in line with how they wish said bodies to.

You’re not likely to see many people with metal hands that sprout scalpel blades. But I think in such a world as the 2020s Progfuture I’m describing, you will probably see people changing how their bodies work in other ways: a hundred varieties of nonbinary people fine-tuning their gender expression with neohormones, psychonauts shredding the borders of human consciousness by hijacking glands to produce mind-altering chemicals, suicide bombers using black-market bacteria and retroviruses to cause their bone marrow to wither and be replaced by tannerite.

What does retrofuture cyberpunk get right? What would be brought into the 2020s progfuture? Widespread domination by corporations seems like it’s not going away anytime soon. Everyone seems to hate it, other than the mainstream, but I don’t see anti-corporate forces marshaling anytime soon. Government ineffectiveness might break sometime soon, but I doubt it: chances are we’re stuck with that one, too. The casualization of violence seems like it might also be something that remains in place.

And, really, so long as there’s future technology, malicious corporate competence, malicious government incompetence, and casual disregard for the value of human life, isn’t it cyberpunk?

Maybe. I’m of the mind that the people who are most interested in arguing that are the same people whose opinion is the least informed, and the most engaged with the aesthetic of cyberpunk but not the ideas.

Progfuture 2077

What’s left here when we edit out the nostalgic parts? How is this not just nostalgia for teenage rebellion?

(Spoilers for Cyberpunk 2077)

So if you were to throw out the world that Mike Pondsmith designed for his game, and layer as much of the plot of Cyberpunk 2077 into the 2020s progfuture I described, what would you get?

In the original game, the central character, V, is either a nomad, a corporate reject, or a petty street criminal who starts working with mercenary Jackie Welles, and eventually a powerful fixer gives them the chance of a lifetime: a job to steal a valuable piece of technology from one of the wealthiest men in the world. In the process, V and Jackie witness the murder of that wealthy man’s even more wealthy-and-powerful father, get framed for the murder, and end up with the valuable piece of technology (an experimental “relic” that holds the consciousness of rock star and terrorist Johnny Silverhand) being traded between them to keep it from degrading – Jackie dies, and V ends up with Silverhand’s consciousness beginning to overwrite their own, a situation very much like being haunted by a bored-sounding Keanu Reeves, who disappeared after trying to destroy the heart of the corporation that aforementioned most-powerful-man-in-the-world ran.

Some of this still holds true. The nomads – itinerant mercenaries, traders, and smugglers who operate in large family units – slot in perfectly, for example, and I see no reason to eliminate the other backgrounds. The social structure, where criminal “mercenaries” are hired by fixers to carry out jobs, doesn’t seem like it would work for long: it would last for six months, and then would be disrupted by an app (call it “Fixr” to fit with the dumb tendency in how these things are named), run out of a server farm on a de-comissioned tanker floating in international waters, that has you carry out poorly-worded and described jobs that people hire you through, and if your rating drops below 4.7/5, then you’re blacklisted. Of course, this doesn’t matter much, because there are thirty different services that do the same thing (existing in White-Supremacist, Black Separatist, Mormon, Pro-LGBT, Socially Conscious, Anti-LGBT, and farmer-oriented varieties, let’s say).

Fixr would have a terrible logo, because all logos look the same these days.

In this version, V and Jackie get updated to Fixr Platinum for getting enough 5-star reviews after their latest exploit, where they rescued a woman from organ harvesters, and jump on the one job at that level that they can get, leading to them having three days to rob the Penthouse Suite of a 5-star hotel outfitted to simultaneously resist a Category-5 Hurricane and a Category-3 Militia. The problem is that the district they’re in is under a lockdown due to an outbreak of genetically modified measles, and they have to navigate a patchwork of different approaches based on the police and a group of neighborhood militias-, watches-, mutual-aid-societies-, and gangs-cum-CDCs that can’t coordinate with each other, and who all are trying to stem the flow despite the fact that a sizable portion of the population thinks that Neo-Measles is a Sino-Nigerian psyop meant to drag down the American economy (it’s all anyone will talk about). What follows is half action movie and half comedy of errors as they have to use the same service that hired them to hire subcontractors to help fill out the different parts of the job and background details (paying rush fees the whole way).

They succeed, but somehow end up accidentally triggering the murder of the most powerful man in the world – an ancient Russian kleptocrat with ties to the notoriously bloody black market Chilean-Afghan Lithium Cartel. They try to make a break with the package, a mysterious retrovirus injection, but have to use it so it can be later harvested from their own DNA when the refrigeration unit fails. Jackie still dies during the shootout, and V, now a wanted individual, presents themself at the meeting point only to find that the client didn’t mean the Knox-Marriott, they meant the Hyatt Deathfortress hotel (or whatever). Two stars. As they’re walking away, a Knox-Marriott death squad shows up because the kleptocrat had bought the Vengeance Package. When V wakes up in the city dump, being pulled out by the kleptocrat’s former bodyguard, a Cartel Huaso in Keffiya and silver spurs (a global south replacement for the Japanese Corporate Samurai that’s a major side character in the original game), they discover that they’ve gone into debt to the Fixr app because they lose their bonus and still have all of those other sub-contractors to pay, meaning that they have to hustle as the retrovirus begins to write over their brain and the consciousness and memories contained in it with the consciousness of a musician-terrorist with the likeness of...I don’t know...Michael B. Jordan? He seems like a good fit.

This is just an off-the-top-of-my-head reworking, but it feels like the 2020s the same way that Cyberpunk feels like the 1980s, and I think that if we’re going to really talk about the future, we need to be able to talk about the present. For too long we’ve been stuck talking about the 1980s, and the nostalgic mode simply needs to stop being the only way we can talk about this sort of thing.

Progfuture Blade Runner

Can we continue this exercise elsewhere?

What does a similar 2020s progfuture version of Blade Runner look like?

Imagine a Los Angeles of 2058 (they call it that, but it’s somewhere further inland. Bakersfield, perhaps.) Climate change has been irreversible for twenty-eight years, and the second generation after this point is already being born – or would be, if there weren’t a major demographic crunch. Schools and nurseries sit empty. Would-be parents turn to chatbot child-substitutes and lifelike substitute pets (because, remember, one of the dangers of climate change is a collapse of biodiversity.)

Seastead enthusiasts always think it would look like this, not like a rusty container ship anchored off an atoll. Image taken from Nanalyze.

Those who can are emigrating to a Galt’s Gulch type settlement on Mars. Those who can’t do that are fleeing to the artificially greening continent of Antarctica or a variety of seasteads. Some people, wanting to emigrate but unable to afford it, agree to become indentured servants (call them “indies” to play on the original novel’s use of “andies”), but discontent among the indentured servants – due to ever-extending contracts and poor conditions – leads to the adoption of a regimen of drugs: a powerful cocktail of dissociative drugs and corrective surgeries to make them permanently compliant. These indentured servants take the first drug, and then wake up, years later, their contract extended to the point where their youth and vitality is exhausted. They were supposed to go under for three years, and wake up thirteen years later.

There are already pharmaceutical companies that trade in human suffering. The Sackler family, the heads of Purdue pharma, have hollowed out rural America, for example. How far is it from trading in suffering and death to enabling slavery?

On some people, it’s impossible to tell who beforehand, the dissociative drugs triggers what is thought to be a quiet homicidal rage, a serial-killer-like state, but it’s actually just that the drugs don’t properly work and they’re forced to live in a fog until they gain enough mental acuity to lash out and escape.

Our Deckard works for the Bureau of Contract Enforcement (or better a free-market Contract Enforcement Agency™), scooping up runaway Indentures on the mainland and killing them: they can’t be sent back, after all, because the drugs didn’t work, and they’re murderously unstable, now.

He receives instructions to hunt down a conspiracy of Indentures who have escaped, one of them having killed a coworker of his. These Indentures are on a new cocktail of drugs that was intended for a “companion” class of indentures, essentially making them into psychological chameleons, able to adapt to any situation. He goes and interviews the niece of the head of the company, a showcase indenture, the Rachel of our story, who isn’t aware that she’s an indenture (that is, after all, the point of the treatment.)

Ideally, our Deckard doesn’t sexually assault her, but this is a dystopian story. It depends on how much of a villain we want our slave-catcher main character to be. I leave it to you to answer. This happens after he tracks down one on an OnlyFans equivalent and tracks her IP address (first to a Nepalese VPN service, then to an apartment.)

The story’s “villain” works here and hasn’t broken even in three years. It’s a zombie firm.

Meanwhile, the Indentures form an alliance with a brilliant drug chemist who can get them an introduction to the head of the “Job Placement Agency” that they worked for. Our Tyrell isn’t a megacapitalist, though: he’s in the middle level of a pyramid scheme, working for an absentee boss who’s already inaccessible on Mars, and this Tyrell can’t answer their questions – first among them being “Who was I? Who am I supposed to be?” For added tawdriness, I’m imagining this being in a suite in a normal suburban office block, with a software development company next door and a largely-unsuccessful venture capital firm one floor down.

We’ve seen modern cities flooded before, but New Orleans is built low and flat. Soon, we will see vertically-oriented down towns flooded the same way.

They hide out in the flooded ruins of Old LA, the waves crashing against the buildings, the tides and currents making it a death trap. Only the desperate or the mad go here. Our Deckard tracks them down by figuring out their phone numbers from the phone on one of the already-killed Indentures and buys their locations from a privatized intelligence service (NSA.biz?) and hires a gang of teenagers who use a boat to salvage things from the old city to silently row him to the hideout. They haggle with him, wanting to be paid in a cryptocurrency he doesn’t have. Eventually, the matter settled, they take him in, and he confronts them.

It’s a bloody, violent climax, made the more jarring because the gang of teenagers are climbing the frame of the building, streaming the whole ordeal. Four camera lenses are locked on our Deckard as he’s dangling down from the roof of the building and our Batty pulls him up – not out of incomprehensible magnanimity, but for the audience these streams represent. He tells his story, and delivers an impassioned plea that might get carried out into the net by the streams, pleading for rights and consideration.

Our Deckard uses his distraction to pick up a shard of glass, mangling his own hand in the process of stabbing the Batty in the femoral artery.

While recovering in the hospital, our Deckard is told that his insurance has been declined, but not to worry: the Bureau has sold his contract and used a portion of the profits to pay for his treatment. In walks his new boss, our Rachel, with an orange pill bottle – she has been released from her own contract and now owns her uncle’s company, and she is very displeased with our Deckard’s behavior.

This radically changes a few things about the original story. First, it obviates the boundary between human and replicant, making the border porous and easily crossed. It thus makes it a much grimmer tale, because there’s no ability to deny that Deckard is a murderer and a hunter of fugitive slaves. However, it also brings in something that is not present in the original that is a subtle but profound shift: in this construction everyone present to the story is under someone else’s boot. No one is free to say no, and everyone’s victimized by everyone else. The real villains are insulated to the point that we don’t even see them.

The Progfuture Anti-Manifesto

I don’t want someone to walk away from this piece thinking that I’m proposing the creation of a cyberpunk subgenre called “Progfuture”. I don’t want progfuture to be a thing, but I’m cobbling this together because every science fiction story that comes out is a retrofuture. If everything is looking backwards, we need a new term to encourage us to look forward – or at least around.

Our inability to productively imagine the future has led to a naturalization of our deeply unnatural present – unnatural not simply because “natural” and “unnatural” are incoherent categories, but because it’s been imposed on us fairly recently and we just assume that it’s always been the case.

Progfuture is a quality that is possessed by science fiction that refuses to be retrofuturistic, and because it is a quality it isn’t a category, the same way that the color blue isn’t a painting: you can have a painting that’s only blue, you can have a painting that doesn’t use blue at all, but it’s a quality possessed by the image, not the category the image fits into.

Cyberpunk began as the genre of progfuture (not articulated as such,) but it simply created an aesthetic, and the aesthetic drifted away from the content, becoming something that could be layered on just about anything else. The revolutionary potential of it was cast aside like so much offal, and the images became a fixed thing.

This is what considering a story as an object gets you. This is why a story should be considered as a process, as something that does something.